Settled: Monty Mahobe worked in a factory for 20 years until he was retrenched in the 1980s. He now lives in Soweto and has now recently published his autobiography. Photo: Oupa Nkosi

Growing up in Sophiatown and later in Western Native Township in the 1940s and 1950s, artist Monty Mahobe was kind of cajoled into drawing by his schoolmates as a boy.

“I don’t know where I picked it up, but I loved handywork, carpentry, tailoring,” says Mahobe, sitting cross-legged in the lounge of his house in Moroka, Soweto. “But I sort of struggled at school because I wasn’t concentrating. When the higher classes would go to the carpentry shop for supplies, we’d be clustered in the classroom [drawing] in our drawing books, looked after by an old teacher just to monitor us. We’d draw imaginary drawings, sort of competing.”

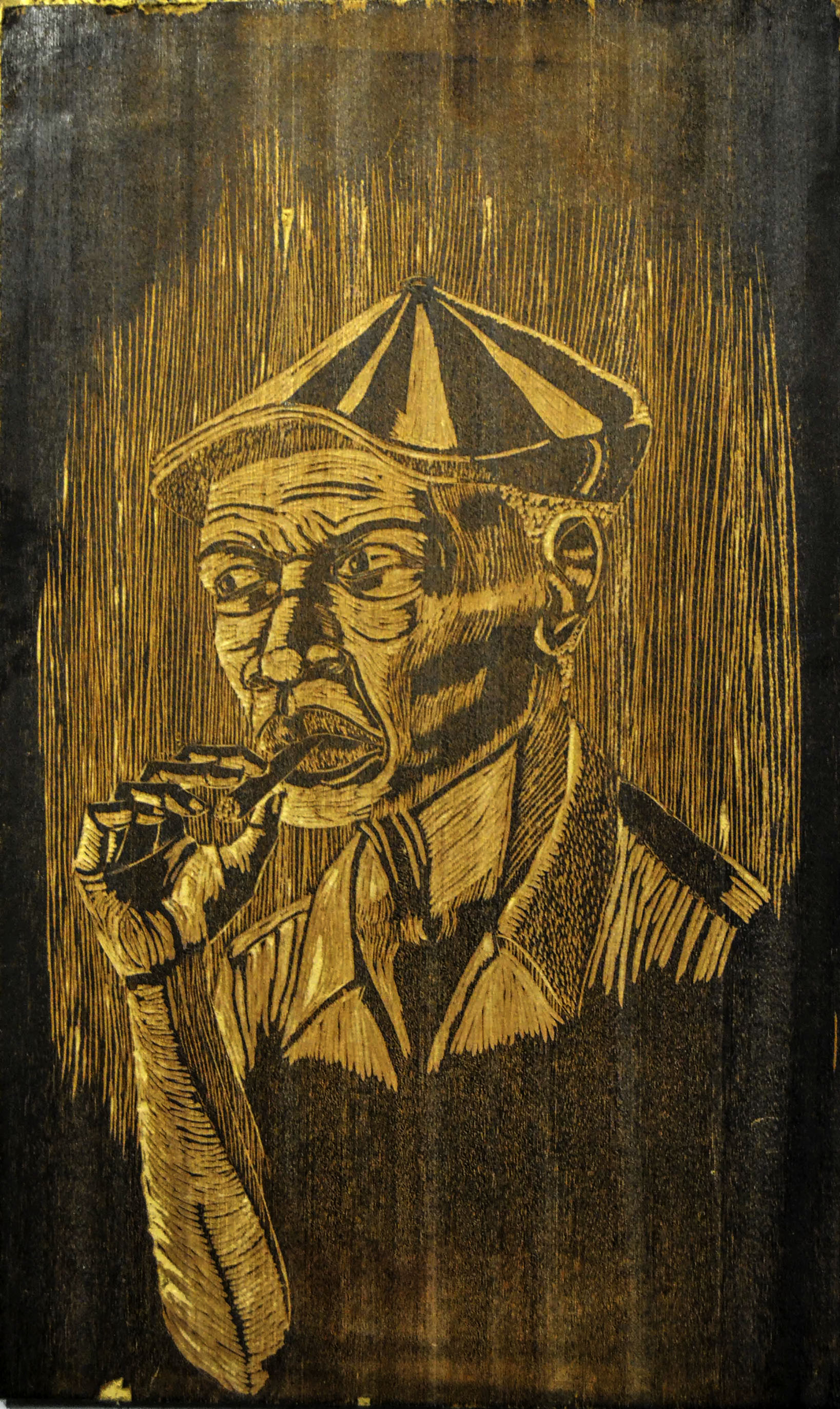

Relief: The Dagga Smoker may have been from the time he lived in Sophiatown

Later trying his hand at watercolours, Mahobe was introduced to artist and arts supplier Matthew Whipman by his father. The two had worked together at the Metro Bioscope.

“When his contract ended, he decided to open a gallery. It was a shop, but the basement he used as a gallery and called it the Whipman Gallery. He gave me material to work with, a lot of watercolours, brushes and he just said, ‘Go home and paint. When you’re finished, you bring them to me.’”

This exchange led to an exhibition in which the young Mahobe made about £40 (the currency of the time). Showing me a watercolour mountain scene foregrounded by a rural homestead,

Mahobe describes the work encapsulated in the battered frame as “all imaginary because I didn’t know about sitting down and looking at the world”. It is a scene from Lady Frere, near Queenstown where Mahobe spent parts of his childhood, as his parents sought to protect him from the dangers of urban township life.

From seeing the potential in his early work, someone introduced Mahobe to the Polly Street Arts Centre, but Mahobe soon fell in with the musician crowd in high school, some of whom he’d make the trek to the arts centre with. “They started late and it was quite far from the buses,” he says. “So I had recruited some other chaps to walk with me, like Stompie Manana and Ezra Mokgae.”

Manana, his St Peter’s College schoolmate, loved the trumpet. “Me, Manana, [Jonas] Gwangwa, we were in form two, all at the same school. Although I wanted to be a tenor saxophone man, [Father Trevor] Huddleston decided that I should play bass,” says Mahobe. “I have two arms,” says Mahobe. “One was bass. One was painting. The weak one dropped.”

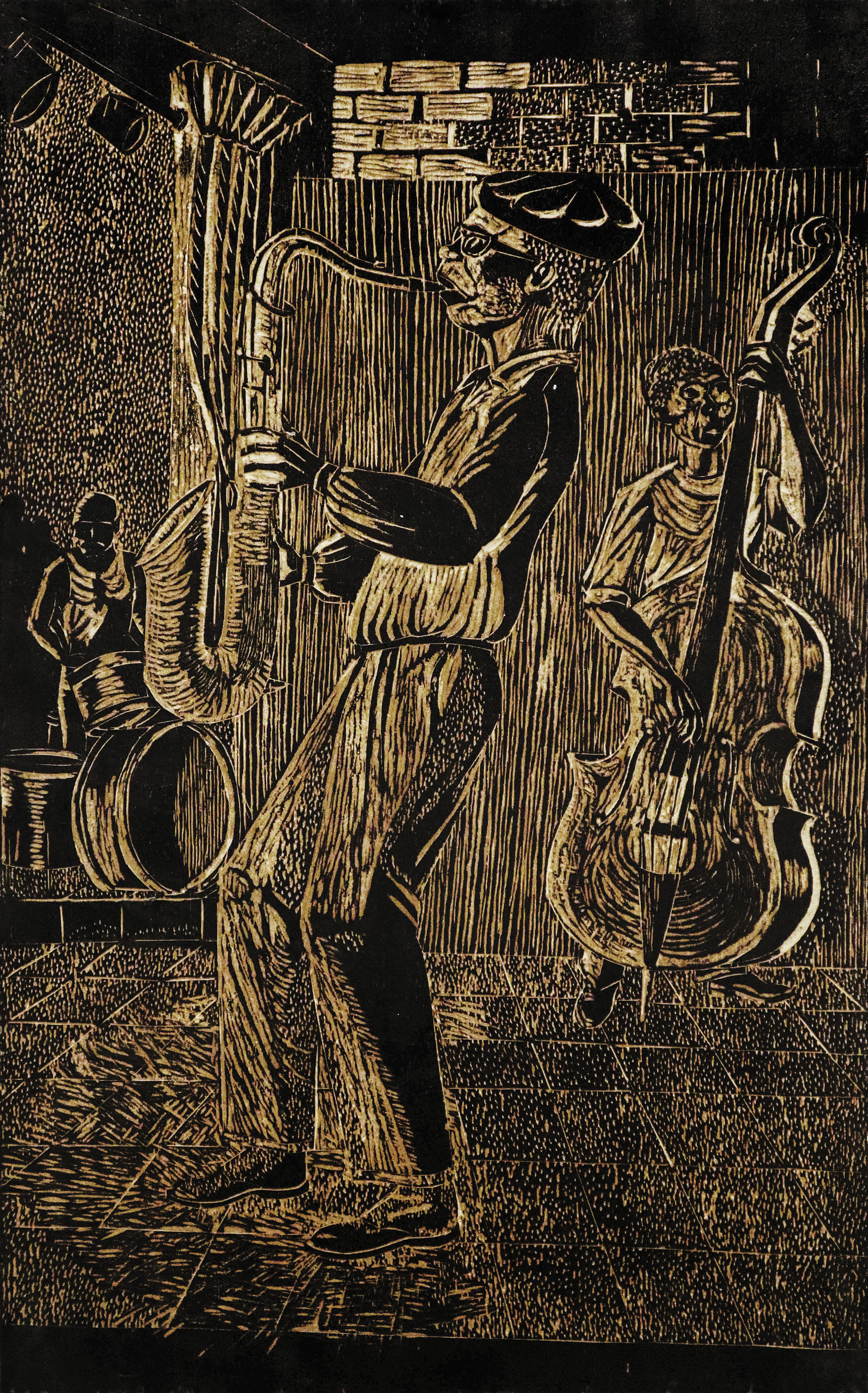

Trio II (All That Jazz): Monty Mahobe was also a musician, but he is dismissive of his ability

In his teenage years leading up to his early 20s, Mahobe played in several formations, culminating in a tour of the subcontinent as a member of the African Follies. Although he was a competent player, Mahobe is modest when discussing his musical abilities. “I completely discarded the bass because I could feel I was playing nonsense,” he says. “I picked up here and there, but when the score was difficult then there would be trouble.

“Then came this thing called bebop,” his eyes lighting up, shifting in his seat to make fast movements with his fingers, as if holding an imaginary upright bass. “That was chord work now.”

After being arrested on his return from a Mozambican tour, Mahobe quit the life of a touring musician. “I felt I was just wasting time with music,” he says, before disparaging his musical abilities. “I couldn’t get what I wanted, anyway. I was just pulling notes.”

There is a linocut print of a man kneeling to embrace his standing parent. In the same scene, another man holds a bull by the horns looking at the reunion expectantly. A marquee and a woman standing near cast-iron pots and bits of wood give the scene a festive air, probably alluding to Mahobe’s decision to settle down into married life. By the early 1960s, Mahobe had taken a job in a spring manufacturing factory in Wadeville. “I worked a week, a month, a year, next thing you know it was 20 years,” he says. “I started there in April in 1963, by December I got married.”

Echoes: Monty Mohabe’s art reflects everyday life, such as Street Repairing

After being retrenched in the early 1980s, Mahobe slowly made his return to art, learning linocutting from workshops at the Mofolo Arts Centre, but mainly sticking to wood-carving because lino was expensive. Many of the works from this period depict musicians. The upright bass features regularly, as do trio formations and even a violinist.

“The violinist had once bought a painting from me in Polly Street,” says Mahobe. “I thought I should try my hand at carving a violinist. I shouldn’t be stereotypical by depicting only things that I know. I thought I should try the difficult things to see if I could make it.”

At a recent group show at the FirstRand Group’s gallery in Sandton, Mahobe pointed my attention to an acrylic on painting with bright colours, fine strokes and a stapled canvas. It depicts a scene of a row of shacks in which mbamba (home-brewed beer) was sold. Some men are lying on the floor and others sit on the benches, their heads on their knees. In the interregnum between retrenchment and returning to art, “that was me”, says Mahobe.

Typical of Mahobe’s work is a tendency to subvert perspective by almost stacking the imagery of a scene upfront. Although in the book Portrait he speaks about struggling with perspective early on in his career, he has worked that into a sort of mystical modus operandi, says book designer and curator Brenton Maart.

His assistant, Nomazulu Taukobong, says that although Mahobe’s works do not follow a specific timeline, many are drawn from memory. A recent series of Mahobe’s work, she says, draws its inspiration from the Marikana massacre.

“Artist Proof Studios have about 32 pieces that span 20 years of Uncle Monty’s work,” says Taukobong. “It is very eclectic, containing images that have to do with Sophiatown. Some of the work is political, but a lot of the time there is a lot around the working class, but the working class and music — how people use music at work, whether they be fixing roads or laying tracks.”

Mahobe’s work, because of how he grew up, tends to flit between the depiction of rural and urban scenes. One scene carved out of wood depicts railway workers lifting sleepers. A few wear umblaselo pants, which have been modified to give their legs a bell-bottom effect. These are travel scenes Mahobe would have experienced as a boy, noting how the workers then were less conservative in their style of dress.

Past: The Rubbish Collectors, a woodcut relief carving, captures the realities of life back then

“They would take some patches off their trousers then tie them on the bottom of the trousers with something like twine or maybe sew it on. But look how it is now, like a dress. Then they didn’t just wear a uniform; they made it look fashionable,” he says, in the portrait.

Taukobong has taken it upon herself to promote Mahobe’s work in spaces where the potential for primary and secondary sales exist. The Unisa Gallery has recently acquired some of his works, he has exhibited in Soweto and he is working on the details of a book deal with a German publisher.

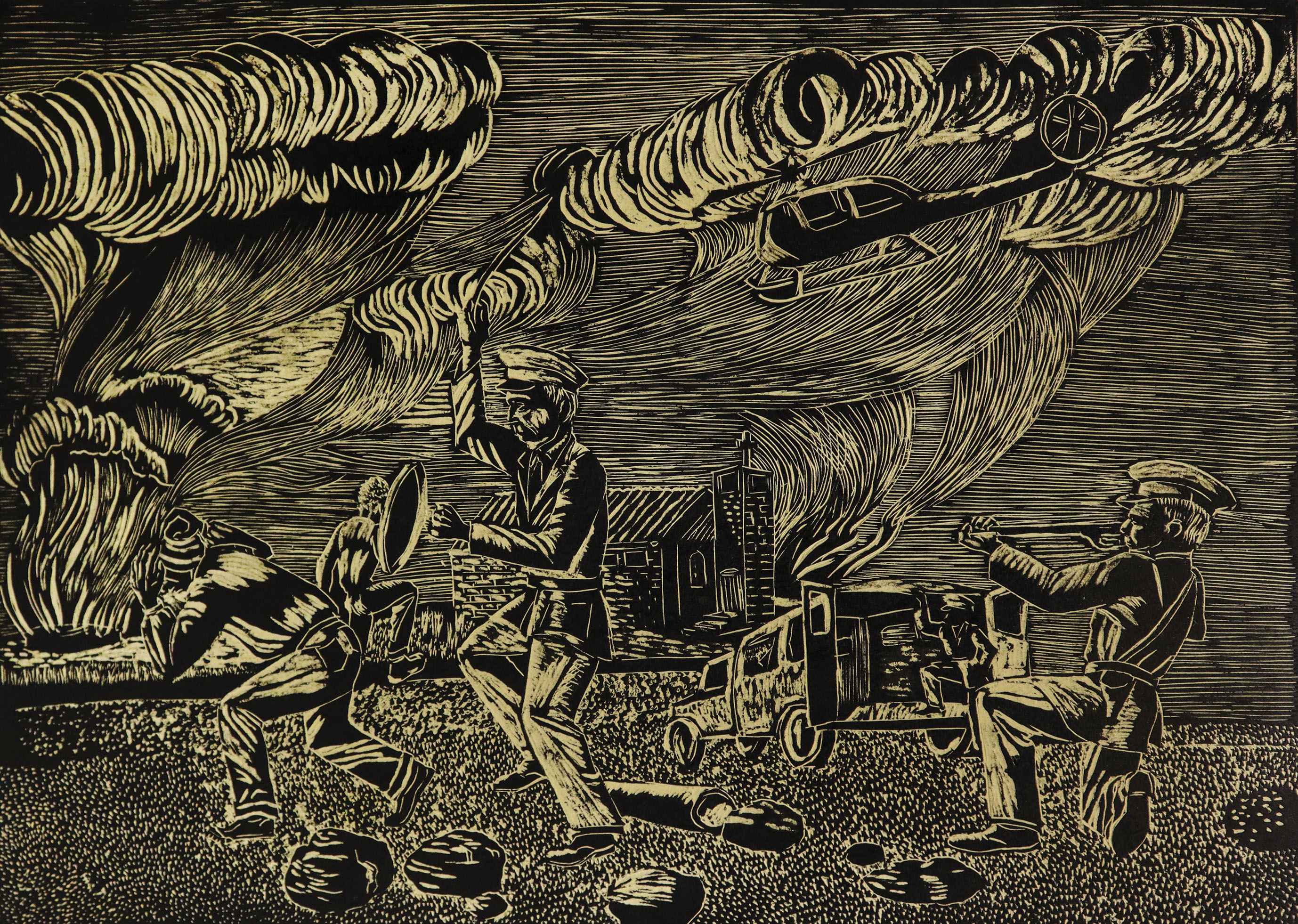

Some of his work depicts the political situation, such as Soweto Uprising

An autobiography book in which the interplay between his work and his life story is elucidated in an interesting, if oddball, fashion was recently published. Maart, the book’s designer, says Mahobe’s treatment of wood and the types of wood he has used over the years, because of limitations such as money, have created a style “in which the substrate is a form in and of itself”.

For a man whose career was truncated by apartheid, his emergence clearly has a rejuvenating effect on him and other artists experiencing his work for the first time.