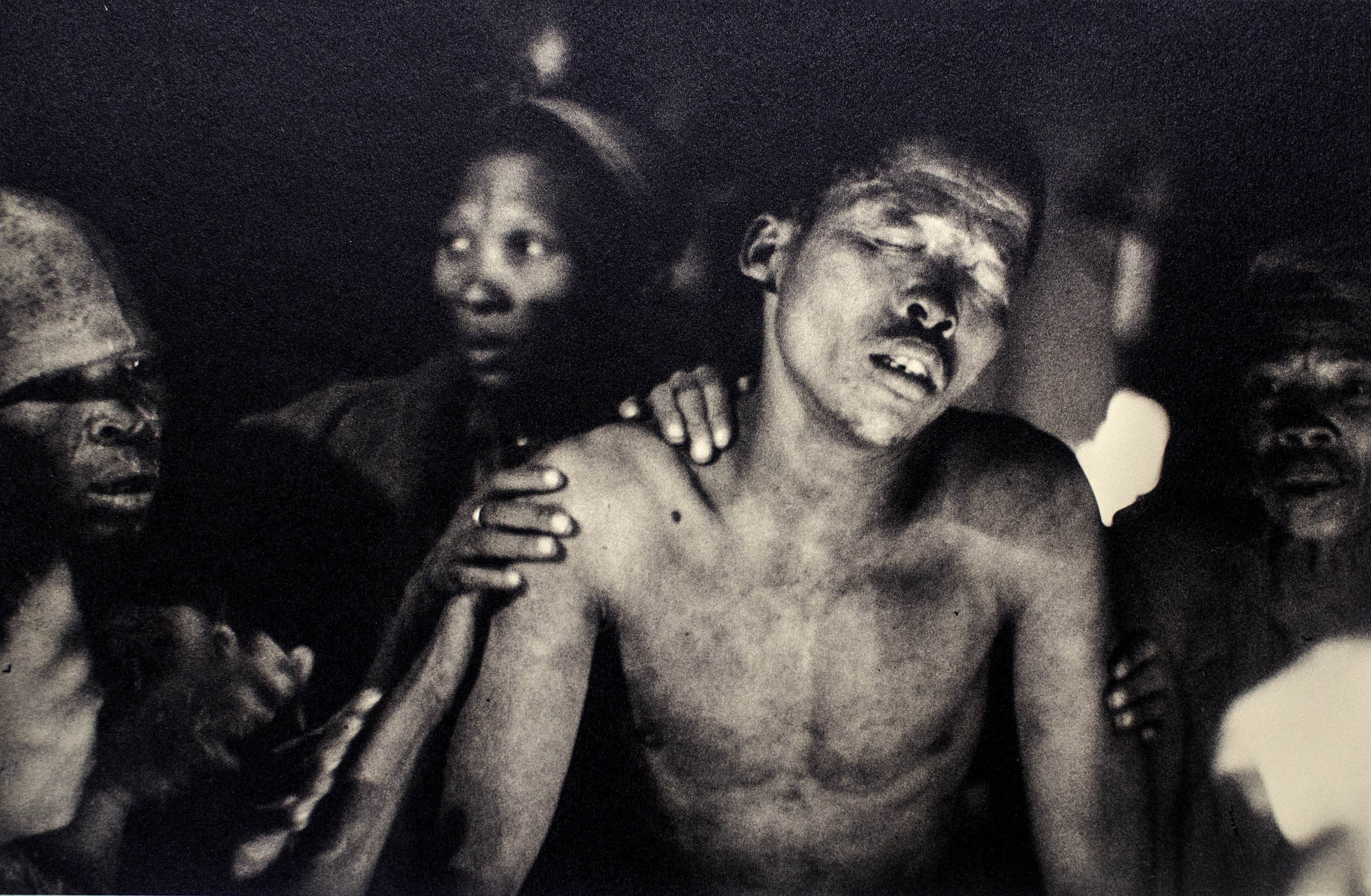

Johannesburg Art Gallery chief curator Khwezi Gule used the works of artists, such as photographs from Steve Hilton-Barbers collection of pictures taken in the 1990s of Northern Sotho initiates to inform All Your Faves Are Problematic

Sometime in 2018, Johannesburg Art Gallery chief curator Khwezi Gule was poring over the gallery’s collection and its attendant archive with the aim of curating a self-reflective show that had long been in gestation.

While digging up material for the show that eventually became All Your Faves Are Problematic, he came across a likely springboard in scholar Candice Jansen’s trenchant review of Jürgen Schadeberg’s memoir The Way I See It, published in the Mail & Guardian in 2017.

READ MORE: Casting history to his own Drum beat

In it, Jansen spent several paragraphs unmasking Schadeberg’s questionable 1959 trip to the Kgalagadi Desert with a crew led by palaeoanthropologist Phillip Tobias. In Ghanzi, in the middle of the desert, Schadeberg had participated in an anthropological exercise in which “different members of the expedition team had different tasks”, as he explains in his memoir. “Some were charged with weighing the San, some with taking measurements of their skulls, jaws, teeth … noses” and labia.

A photograph by Jürgen Schadeberg taken in the Kgalagadi when he accompanied palaeoanthropologist Phillip Tobiasin in 1959.

Sacred rituals were similarly prodded and observed, and photographic records were kept that today form part of the gallery’s collection.

Another “node” that offered distinct directions for Gule was the work of 19th-century French cartoonist Honoré-Victorin Daumier. For Gule, the artist’s work occupied the dual role of critiquing the day’s bourgeoisie while at the same time being “overtly racist”.

Three of Daumier’s cartoons (at least two dealing with curious European encounters with “the other”) are photocopied on to A2 white paper and pasted on a wall in what one might call a strategic alcove in the gallery. In the way the show has been mapped out, Daumier’s works are hemmed in by diagonally mounted metal shelves, each containing a row of books that might broadly be grouped as “post-colonial knowledges”, crucial in terms of speaking back to the established academy.

The works of Daumier, in particular the intent behind them, bring up questions that are echoed throughout the show to varying degrees. This makes All Your Faves Are Problematic a coherent and refreshing contribution to the discourse about the blind spots that permeate contemporary South African art and its preceding stages.

As an intervention, the exhibition is premised on moving beyond the “show-and-tell” approach in terms of how national cultural institutions have tended to deal with their own collections, a condition partly brought about by the fact that the collections span several eras of South African social life and cultural production. They encompass the colonial, apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

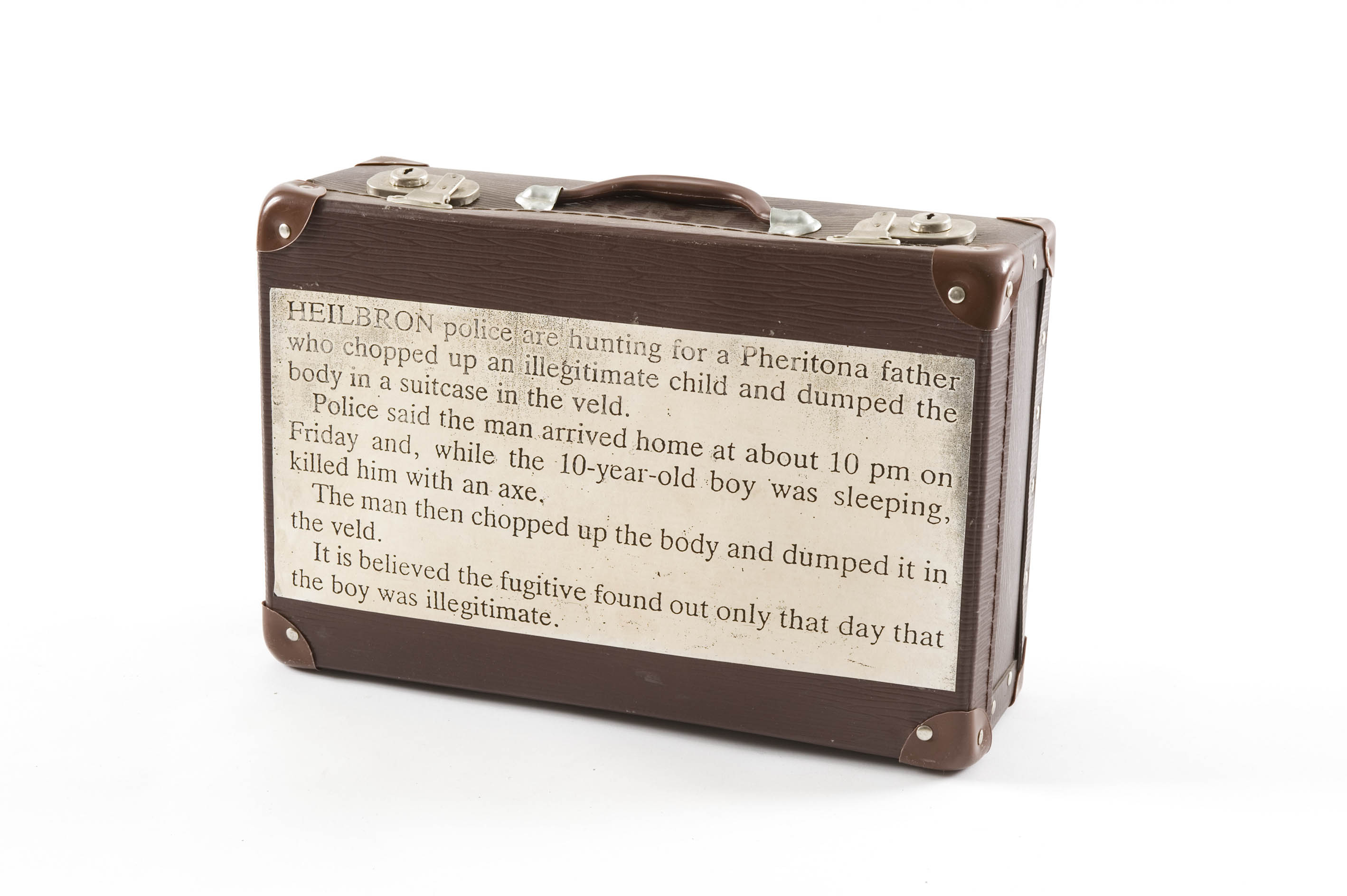

“There are two ways that most people deal with collections,” says Gule, seated in front of Kendell Geers’ contentious work The Suitcase, while preparing to be filmed for a video interview. “One way is to resort to amnesia, to just pretend that they are not there, or even if we are looking at the images, we are just presenting them as is. The other one is to approach them with a sense of nostalgia, which is to look at them and marvel at their beauty or the brilliance of the artist without the political context in which the artworks are made.”

The Suitcase by Kendell Geers

Although Gule is at pains not to deny people their preferred method of engagement, especially given the trauma associated with the colonial and apartheid encounters, he adds that “we who take on these institutions, either as members of the public or as people working here, have to confront these things on a daily basis. We are responsible for them. In fact, all of this collection belongs to the residents of the City of Johannesburg.”

Because the discourse about art has happened within an oppressive context in South Africa, it has invariably produced “holy cows”, protected by an underdeveloped art discourse and exclusionary practices that discourage forthrightness and discursive diversity.

Several “holy cows” spring to mind, primarily because of the prominence they are afforded in the show, either because of where they are placed or because of the number of works selected for display. Among these are William Kentridge, Irma Stern, Jodi Bieber, Peter Hugo, Paul Stopforth, Sue Williamson, Walter Battiss, Anton Kannemeyer, Pippa Skotnes and Cecil Skotnes. In the way the show has been framed by the curator’s statement, Geers is less emblematic of the holy cow syndrome than he is of our habit of asking the wrong questions.

“In the late 1980s and 1990s,” reads the statement on the Friends of JAG website, “people objected to his work because they felt it crossed the boundaries of taste, while others wondered if it was even art. But this is not the most pertinent indictment of his work.”

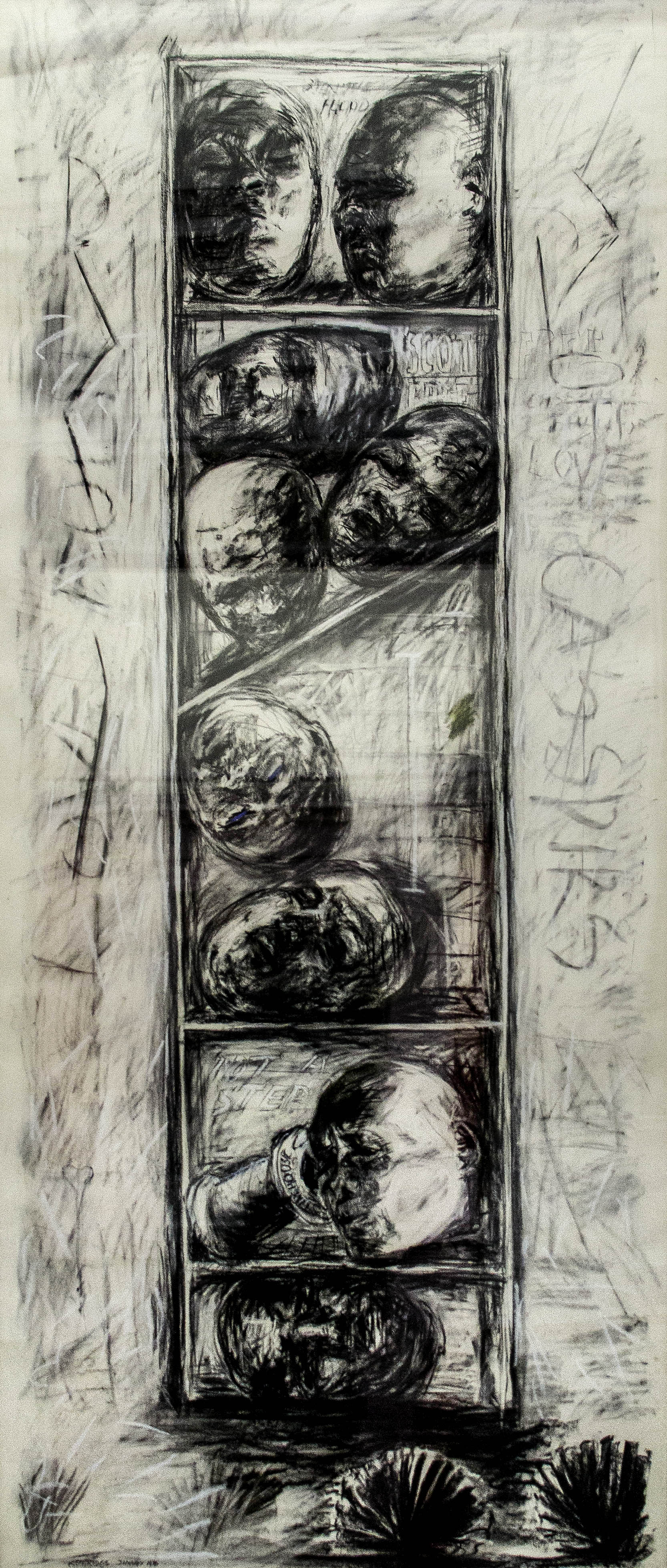

Through the lens provided by Geers’ The Suitcase, and, indeed, Kentridge’s Casspirs Full of Love, Stopforth’s Biko series (graphite on wax works, depicting the isolated limbs of Steve Biko’s bruised, unclothed and tortured body), Hugo’s Rwanda series and others, Gule studies the fascination with dismemberment, voyeurism and the treatment of the suffering of others as glib spectacle.

William Kentridge’s Casspirs Full of Love

A Susan Sontag quote from Regarding the Pain of Others, placed diagonally across from Stopforth’s work, reads: “It seems that the appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.”

Although Stopforth has been valorised by white liberal scholars for his work, especially given how close in time it was to the death of Biko when it was produced, under Gule’s framing it takes on a morbid tint, narrowing its distance to Hugo’s ghastly skeletons from the Rwanda series and Steve Hilton-Barber’s sensationalist and unscrupulously voyeuristic early 1990s works, the Northern Sotho initiation series.

Although from the names alone one can imagine the sweep of the show to be wide-ranging, the curator anchors it, to a certain extent, in photography. He draws liberally from Bieber’s series Kom Blom Met Ons (produced from Bieber’s mid-1990s project in the company of Westbury’s Fast Gunz and their younger detachment, the Jonathan D Boyz), pitting them against Schadeberg’s Kgalagadi photographs and Hilton-Barber’s initiation works.

Although Bieber has been fêted globally for shining a light on the marginalised (she won a World Press Photo Award for her image of Bibi Aisha, an Afghani girl who was tortured) and “humanising” Soweto (the title of one of her books), Gule thrusts her work into a conversation about the uneven power dynamics thrown up by her mere presence in the company of gangsters and how her camera may have influenced the turn of events.

Although Hilton-Barber’s subjects are shy, ill at ease and embarrassed, even, Bieber’s Fast Gunz, at times, are full of bravado.

“Look, Bieber might be a perfectly good human being trying to do good but that also doesn’t excuse the work itself from some of the very well-known problems surrounding documentary photography, such as the issue of voyeurism, for instance,” Gule says.

“How do you deal with those kinds of problems especially when those issues pertain to relatively poor communities? How do you, as a white artist, navigate in areas where you carry with you a certain degree of privilege and historical baggage?

“I don’t have the answer for those people and, just because I don’t have the answer, it doesn’t mean I mustn’t already critique what is already there.”

It is Stern’s Bahutu Musicians, an almost life-size oil-on-canvas rendering of a group of musicians that has come to be the poster of Gule’s show. When looking at it and other works such as Native Study (a charcoal drawing from 1938), one can’t help but be reminded of Stern’s quote about personal contact providing “a few glimpses into the hidden depths of the primitive and childlike yet rich soul of the native”.

While discussing the conundrum of choosing a possible cover image, Gule seemed sensitive to the possibility of reproducing some of the more shocking images contained in the exhibition.

He pored over 10 000 objects to bring about the thread that is All Your Faves Are Problematic, one wonders what else lies in the collection, grim or otherwise, that may one day see the light of day if Gule doesn’t falter in his quest to engage critically with his bird(s) in hand.

All Your Faves Are Problematic, which takes its title from a Tumblr blog, runs at the Johannesburg Art Gallery until the end of February.