The virtual literary festival takes place from March 23 to 30.

“I never wanna see it. I’m gonna cry if I do. I’m okay. I’ll die under a pile of books” is how book-lover Lethabo Mailula (24) responded in a discussion regarding Japanese organising consultant Marie Kondo’s take on bibliophilia. In her book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, she writes: “I now keep my collection of books to about 30 volumes at any one time.”

For giggles, a Twitter user with the handle of Reverend Jeremy Smith altered this statement and attached it to a picture from Kondo’s Netflix show, Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, to create a meme that reads: “Ideally, keep less than 30.”

Kondo has since cleared up the misunderstanding, saying that she only encourages readers to keep books that “spark joy”. But many think pieces objecting to the idea of downsizing, selling or donating literature had already been written.

Mailula herself has just managed to cull her 16-year collection of 446 down to “only 276 books”.

The collection began when, as an eight-year-old, she preferred rereading her first book, Harry Potter and The Philosopher’s Stone, to watching cartoons. By the time she reached high school, getting books from the library or only when she asked her parents if she could go past the local bookstore was no longer enough.

“I ran a lollipop empire. I sold Pin Pop sweets, which were banned from our school because of its preoccupation with health foods. I used the proceeds from that to buy books. I even made the librarian order some books that weren’t in the library,” she recalls.

Some of the titles include Zakes Mda’s Madonna of Excelsior, Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, Antjie Krog’s Country of my Skull and The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini. Fresh from her high-school hustle, Mailula then juggled working at a bookstore with studying and tutoring at the University of Pretoria to fan the reading flame.

“There was something intoxicating about walking into the bookstore at the end of the day and just choosing which world I would like to lose myself in.”

Unlike Mailula, some bibliophiles have no plans to part with their literary loves. Playwright and literary critic Sandile Ngidi has lost count of how many books he has acquired since 1983, when he “was looking for role models as an aspiring poet”.

Sandile Ngidi is compelled to collect books on subjects that intrigue him. Photo: Rogan Ward

He keeps the top 300-and-something of his collection in his home study, and his only concern about this subject is the thought of loss.

“When I lived in Brixton [in Johannesburg], one of my cousins brought friends to my house. I contemplated the possibility of his friends stealing my books. My cousin laughed, because it was unlikely that they would prioritise stealing books in my house, if they were thieves at all.

“But books become your friends over time. You guard them jealously. Of course, some of it may appear neurotic but I don’t think I’m neurotic. I’m just in love,” sighs Ngidi.

During National Book Week in 2017, news broadcaster eNCA published an article by writer and news analyst Angelo Fick, whose home has a library of more than 27 000 books.

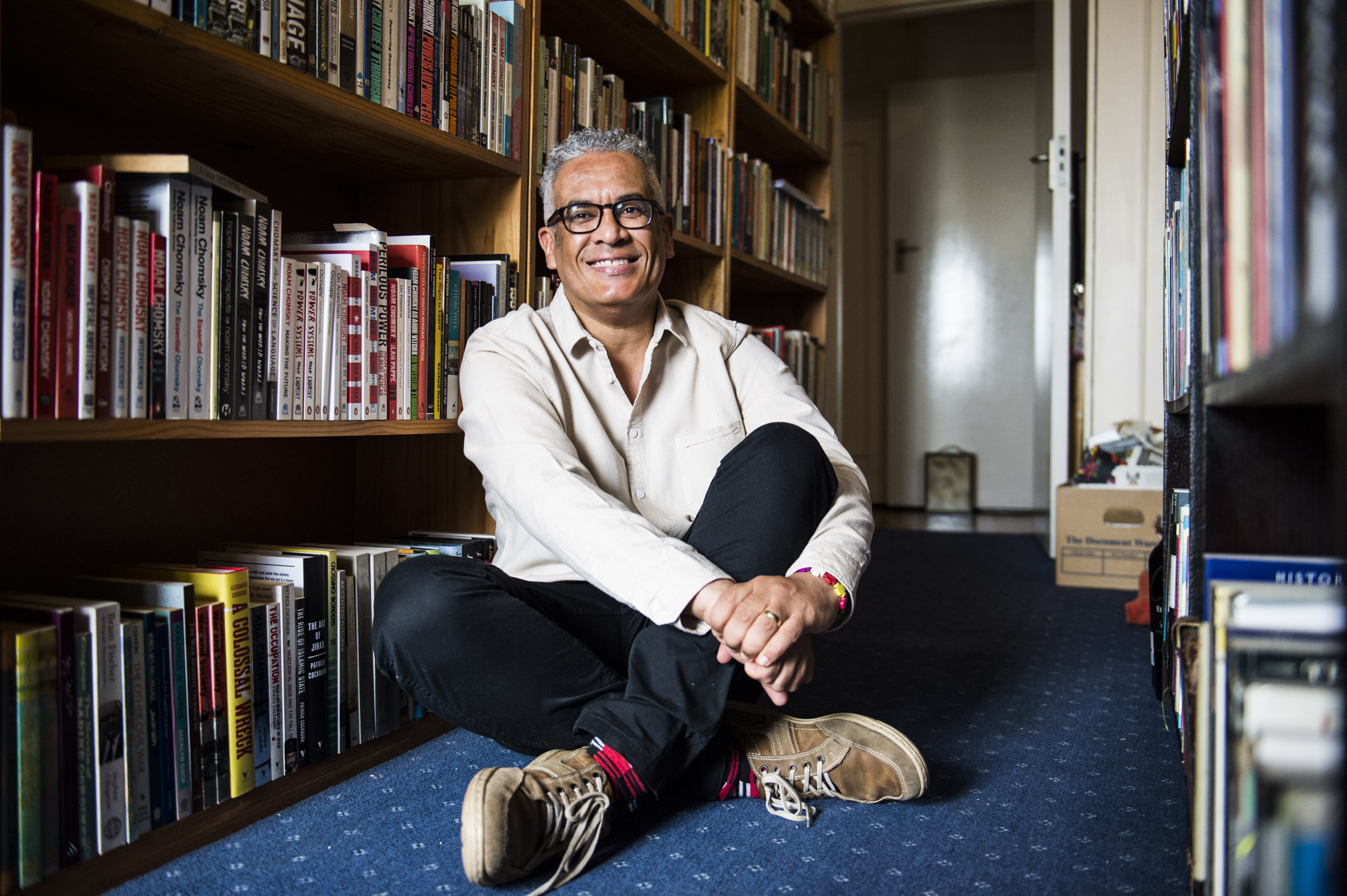

Bookworms: Angelo Fick has a collection of 27 000 books. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

He wrote: “Books are lifelines. They allow us to be still, to pause, to stand aside from our lives in order to re-enter that living more empowered. Books are not luxuries; they are essentials. Some of us are alive now because we had and have books, because we were never meant to survive [otherwise], to invoke Audre Lorde.”

Easily accessible books are not enough. Bibliophiles such as Mailula, Ngidi and Fick often rely on second-hand bookstores, where you can find things that aren’t always available in commercial bookstores, to top up their collections.

One such bookstore is Collectors Treasury on Commissioner Street in Johannesburg’s Maboneng. Run by brothers Geff and Jonathan Klass, the shop has more than two million second-hand books and is said to be the largest bookstore in the southern hemisphere. The brothers established it in 1974 with their mother, Maisie, who, like their father, was a book collector.

“We were brought up in a house of collecting. We reached this stage where we decided it was time. We started with excess from our collection and started acquiring more books from a wide range of sources, leading up to our opening,” says Geff.

Collectors Treasury is “the” destination for book lovers 45 years later, even though the owners were accused on social media of racially profiling their visitors after one of them took photographs of customers after a break-in.

Other shops where rare finds can be unearthed include Bridge Books, book vendors near Park Station and Love Books — and these are just in Johannesburg.

When asked why he keeps the books he has read, Fick says it has to do with anchorage. “It’s partly superstition, partly visual stimulation. Seeing the books on the shelves, walking past them on a regular basis provides a type of anchor, so I’m more likely to remember the content and issues around a book that I read.”

In the same way, Ngidi’s collection continues to grow because whenever he discovers an author or subject matter that interests him, he is compelled to acquire all the books related to it. “Not that I’m gonna give them away but, if it’s rare, I make sure I have more than one copy of the book.”

Ngidi and Fick no longer lend their books out, even to loved ones, because they either are returned in an unfavourable state or they are not returned at all.

The book lovers I interviewed all believe the books they own “spark joy” but many can’t afford to buy them.

Late last year, at about the time of the Kondo uproar, Kenyan writer and author of Migritude Shailja Patel offered an alternative line of thinking, as a book lover who grew up relying on libraries to appease her literary hunger.

She said: “I keep seeing people I respect sharing that ‘buy more books than you can ever read’ BS piece in [the journal] Fast Capitalism. What is it about the word ‘books’ that casts a magic veil over naked commodity fetishism?”

Patel went on to urge people who have the luxury of adding to their collections rather to put money into the public circulation of books. “On giving rather than hoarding books. On sharing rather than accumulating books. On getting books to everyone hungry to read them and be transformed.”

In Fick’s essay, he wrote: “Books here are too expensive, taxed and levied beyond the reach of many who live in this country, where more than half of us are poor. Libraries are not nearly well-supported enough, either by funding or by political planning. And the hunger for books, the voracious reading of ordinary people I have observed tells me this is not some middle-class obsession.”

In response to this, Mailula has begun donating books. “The 276 books that I kept are my absolute life-changers. Audre Lorde. June Jordan. K Sello Duiker. [James] Baldwin. I have embarked on a journey of reading books by people who look like me,” she says.

Ngidi and Fick say they have always been open to giving people books, as long as they can maintain or increase their personal libraries.