'We can still succeed economically, regardless of corruption, by increasing social cohesion,' writes Dino Galetti.(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Understandably, many South Africans are anxious about recent events. Having survived the Guptas, many believe corruption poses the greatest threat to our economy, the government and the nation’s future. But the Gupta network is still intact, and indeed both the charges laid against them last year have been dropped, implying that South Africa is still in the grip of state capturers.

That fear is reinforced by the ANC’s inability to fix Eskom and SAA, which it is still bailing out. Worse, commissions of inquiry are revealing a staggering breadth of corruption but still no action is being taken.

In this culture of impunity, opportunists are emboldened to pilfer from public coffers, so society seems to be decaying. Many people are clamouring for one prosecution — just one — to reassure them that President Cyril Ramaphosa is able to solve matters.

The alternative, they fear, is catastrophe — the return of Jacob Zuma’s faction and State Capture 2.0; yet still, Ramaphosa’s ANC pays lip service to eradicating corruption while seemingly unable to fix it.

This causes a vicious circle of anxiety. The demand to eradicate corruption is made to the government but lack of progress leads to demoralisation, then to increasing anxiety. That leads to unwise confrontation, such as Helen Zille’s threat of a tax revolt (all a tax revolt would do is impede Ramaphosa and make him vulnerable to recall). Or else it leads to despair.

Unfortunately, the cycle is unlikely to be resolved, because the public overlooks four basic influences.

First, Ramaphosa only narrowly won the 2017 ANC election and is still outnumbered by his predecessor’s cadres in government. He is not strong enough to take major action, and this is unlikely to change soon.

Second, the commissions of inquiry show that corruption runs so deep that the ANC could never root out even most of the perpetrators, because that would eviscerate their party.

Consequently, lip service to change is the only possible ANC response. Corruption, unfortunately, is here to stay. And that is what the public, locked into a circle of anxiety, greatly fears — it would then seem guaranteed that we will become a failed state.

Third, in response, many believe their only power is their vote, hence some plan to support the ANC in May to signal support for Ramaphosa.

But even if a landslide victory brings the ANC’s national executive committee (NEC) behind Ramaphosa, it’s likely that a trans-party faction (between the VBS-tainted Economic Freedom Fighters and the Zuma/Gupta faction and their supporters, who have launched political parties) will take the fight to Parliament. Their objective would be to shift the battle from the NEC recalling Ramaphosa to a vote of no confidence. The battle will continue.

But I suggest that there’s more hope than there seems to be, and even a plan.

Because the fourth, overlooked factor is that corruption isn’t always all bad. Scholars record several nations — China, South Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan — that attained massive growth despite ingrained corruption.

I distinguish three kinds of corruption: the parasitic, the symbiotic and the saprophytic. The parasitic kills its host, like the Gupta’s kleptocratic taking of commissions from national debt. That has to be avoided. China’s corruption was reportedly parasitic, so the authorities have had to continually act against it.

Symbiotic corruption coexists with business and government without killing it. For example, Bosasa was practising it during former president Thabo Mbeki’s years, when South Africa’s economy was growing fast and reducing inequality. Taiwan and Vietnam reportedly had that kind.

But the third kind, saprophytic corruption, although it’s immoral, can actually be beneficial.

United States professor of economic history Michael Rock explains: “The Park [Chung-hee] government [in South Korea in the 1960s] provided [a small group of] capitalists promotional privileges — particularly cheap credit from state-owned banks and monopoly privileges in local markets — to grow their firms.

“Promoted firms were expected to meet government-mandated export targets. If the capitalists met export targets, they got more privileges. If they did not, they lost, or were threatened with the loss of those privileges.

“In exchange, promoted firms kicked back a share of their profits to Park and his political entourage. They used the kickbacks to finance election campaigns, buy supporters and enrich themselves. In this model, corruption was growth-enhancing.”

Indeed, this model gave rise to the chaebols, great family-owned enterprises such as Samsung.

That said, the common factor among all those successful nations was social cohesion, which other corrupt nations lacked, as do we today. But their success proves we can still succeed economically, regardless of corruption. They even give us clues on how — by increasing social cohesion — and scenarios to get there.

Currently, the struggle between the ANC factions is balanced. Ramaphosa has the presidency by slim control of the NEC, whereas Zuma’s faction has greater numbers in government and is hanging on by resisting the restoration of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) through their middle management and Parliament and by paralysing law enforcement.

The longer that this stand-off persists, the greater the chance of debt default, the recalling of Ramaphosa and the restoration of parasitic corruption.

Hence, first, in the best-case scenario, if Ramaphosa becomes dominant and winnows out the key state capturers, our legal institutions will be restored. There will be some pro-secutions, and corrupt people outside established networks will be warned to desist.

But much of the previous corrupt government and business connections will remain. South Africa will move from parasitic to symbiotic corruption; however, the government will remain less than effective. Long-term success will rest on social change.

In a weaker scenario, Ramaphosa achieves no prosecutions, although his process of replacing key personnel may gradually restore key institutions, including law enforcement. Until then, corruption will remain endemic and growth will stay tepid and troubled. We’ll stave off disaster but remain a poorly functioning nation.

Next, if the factions stay balanced, then, either because of mounting national debt from failing SOEs or because of inflammatory rhetoric about worsening income inequality, Ramaphosa could be recalled; the corrupt network eventually destabilises the country, ushering in the final scenario — the Zuma faction returns and parasitic corruption begins again.

Notice that the large-scale prosecution of the corrupt ANC body is unlikely, in fact almost impossible, so even the best of these outcomes might look bad. That’s why I add another possibility — “amnesty”; the corrupt are given immunity for past crimes.

Idealists might refuse this because they want payback. But amnesty is not defeat. It would be exchanged for desirable benefits, such as the deparalysing of police bodies; reclassifying corruption (parasitic corruption could be reclassed as treason); eliminating current corrupt contracts, including those hurting SOEs; and agreement that large-scale corruption in future would invalidate the amnesty.

The first would inhibit the slow rot at the peripheries of government and business. The second would preclude parasitic corruption, and implant a regulatory framework that reduces corruption afterwards. The third would help to stabilise our economy against a debt default and have the immediate benefit of attracting investors. The fourth would make the formerly corrupt actually police other corrupt agents, becoming de facto good citizens again, because, if the amnesty is aborted, all their welfares are at stake. Lastly, it would allow a real ANC unity, while letting society look ahead to more important issues.

That said, Ramaphosa is currently unlikely even to broach amnesty, because it would risk voter backlash. The public would need to demand it.

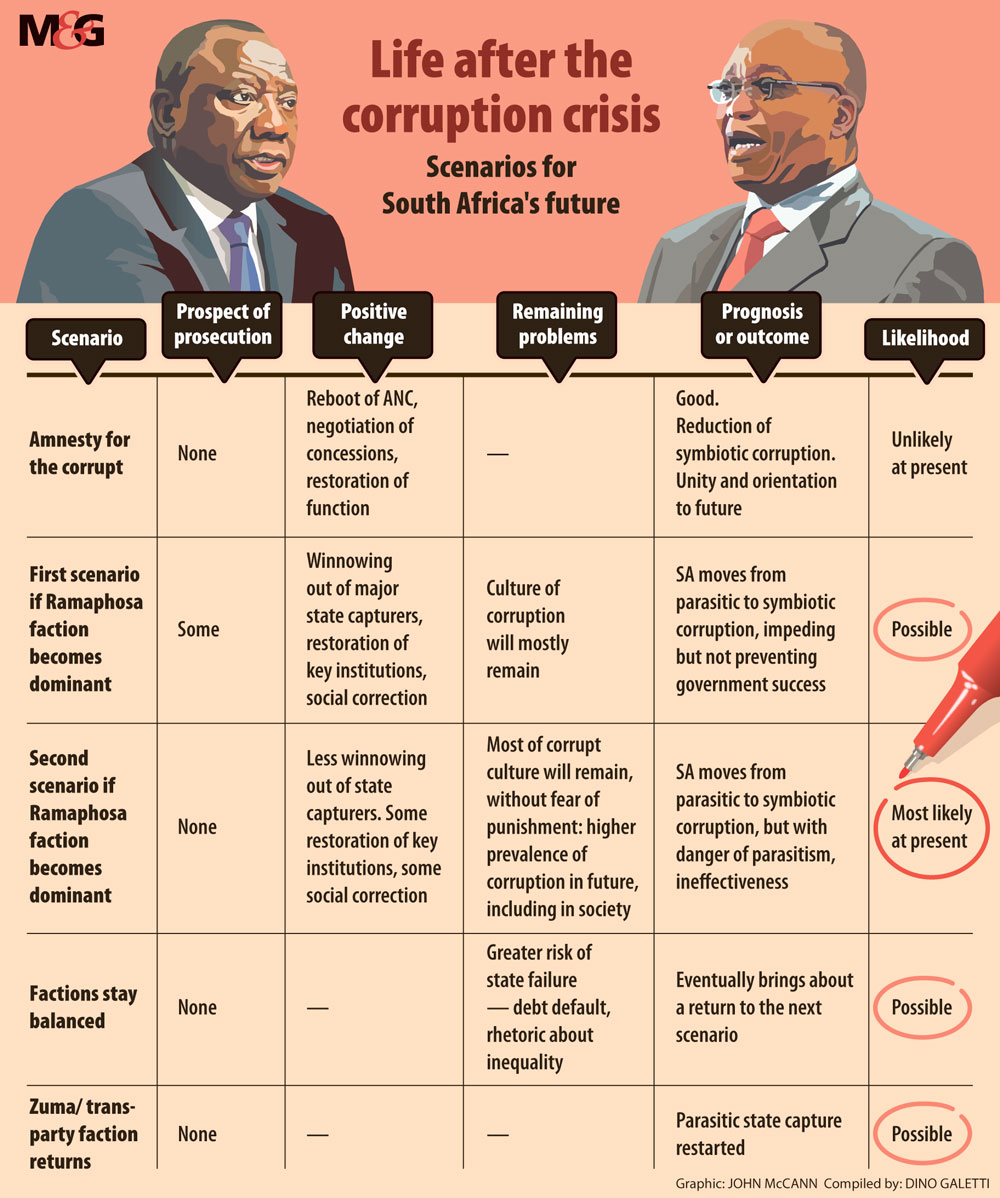

Even without amnesty, though, our reasoning gives us options, summarised in the graphic.

The gist of this is, if we remain in a state of symbiotic corruption, South Africa’s success will depend on strengthening our society — improving social cohesion and capacities — to put increasing pressure on the government to change in the long term.

This will entail improving education, so people can both see through rhetoric and hasten economic turnaround by increasing their own productivity, while instilling what former public prosecutor Thuli Madonsela calls “democracy literacy”, so that voters demand correct action from the government.

But crucially, should the Zuma faction return, it will be incumbent on society to convince them to move from parasitic to saprophytic corruption. We will simply have to show them they can make far more money from long-term saprophytic corruption in a growing economy than from once-off parasitic corruption in a ruined economy.

This is not to say anyone should stop fighting graft. Corruption always takes money that could be used by government for the poor. But unless it’s parasitic, it needn’t stop us succeeding. We need to be able to see it as just an immediate problem, to plan for the long term.

All this means there’s no need to despair. Even a return of the Zuma faction wouldn’t necessarily be the end; it would just entail a different kind of strategy. Ultimately, South Africa’s success will reside not in overcoming entrenched corruption but in achieving dramatic changes in society that turn us into a dynamic nation. That’s much more hopeful than many might have supposed.

Dino Galetti, most recently a research fellow at Yale, is a political commentator. This is an edited extract from his book, How to Reach the Rainbow Nation, due in late 2019