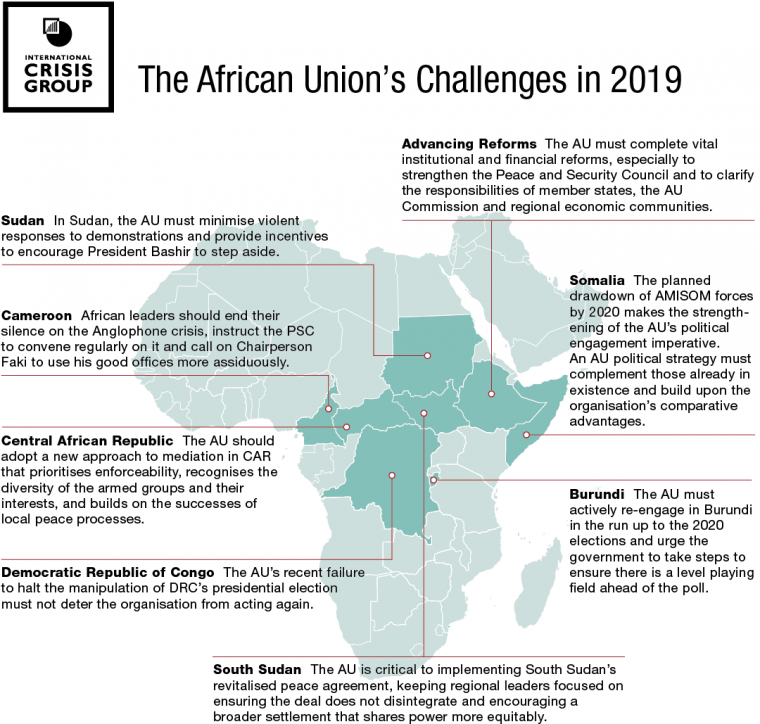

In 2019, the African Union faces many challenges, with conflicts old and new simmering across the continent. To help resolve these crises, the regional organisation should also push ahead with institutional reforms. (Reuters/Tiksa Negeri)

COMMENT

With this commentary, coming in the wake of our annual Ten Conflicts to Watch and EU Watch List, Crisis Group turns to what 2019 will mean for the African continent and the African Union (AU) ahead of its February summit. The broad trends identified in those two preceding publications are mirrored here as well, to wit: a transition wrapped in a transition, wrapped in a transition.

The first transition is occurring at the local level, where entrenched governments face a perilous mix of social unrest and political contestation. 2019 is still young, but it already bears ugly scars of violent repression, in Sudan, Zimbabwe and Cameroon, as well as older wounds from persistent crises in places like the Central African Republic, Mali, Somalia or South Sudan. The remarkable transition witnessed in Ethiopia stands as a powerful counterpoint, but in too many places — as elsewhere across the globe — autocratic rule, immovable elites, predatory state behaviour and corruption are fuelling popular anger. A question we pose in the pages that follow is whether the African Union is up to the task of dealing with these challenges.

Which brings me to the second transition, taking place at the regional level: faced with persistent and seemingly intractable crises and determined not to allow non-African powers to project their agendas onto the continent, the African Union has been searching for ways to better address issues of peace and security. There were some notable diplomatic advances in the past year, led by Moussa Faki Mahamat, AU Commission chairperson: easing tensions ahead of a fraught election in Madagascar, defusing a crisis around a constitutional amendment process in Comoros, and bringing the parties to the table in the CAR crisis, even if the agreement’s implementation remains a challenge. But cracks have been showing in the AU’s overall approach.

In particular, charged with maintaining continental stability, the Peace and Security Council (PSC) has become more tentative since the AU Assembly overturned its December 2015 decision to send an intervention force to Burundi. Too, its agenda increasingly is packed with thematic deliberations on important topics such as child marriage and illicit financial flows, but at the expense of discussions regarding existing and emerging conflicts. At the AU’s July summit, leaders curtailed the PSC’s work on Western Sahara in order to mollify Morocco, which had re-entered the AU in 2017 following a 33-year absence, and assigned a troika of heads of state plus the AU Commission chairperson to report directly to the AU Assembly. That’s an unfortunate precedent, and one that could severely undercut the PSC’s ability to assert itself in future crises. What is needed now is the kind of institutional reforms championed (with varying and uneven success) by Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame. What is also needed is the kind of political assertiveness to involve itself in domestic affairs with a legitimacy and sensitivity to local realities which the West typically lacks.

The locus of the third and broadest of these transitions is on the global stage, where shifting power relations revive old-style great power politics. The impact on the continent might not be immediately clear, but it is palpable nonetheless: China’s increased economic involvement; Russia’s intermittent political/military forays (see, eg, Libya, the Central African Republic or Sudan); and, after a period of dimming attention to Africa regarding anything but its counter-terrorism priorities, the U.S.’s reawakening, less out of any particular preoccupation with the continent’s well-being than as an offshoot of its intensifying rivalry with Beijing. It would be good, in theory, to see such revived interest in Africa and its affairs; not so good to see it inspired by a scramble for influence rather than a search for stability, peace or development.

2019 is still young, as I noted, but already the AU’s track record has been mixed. In January, faced with an electoral crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), it first hinted at a bold stance before retreating into silence and confusion when its efforts were rebuffed by Kinshasa. Elsewhere — from Sudan to Cameroon — it has struggled to make its influence felt. From reforming institutions, to safely and credibly steering political transitions, to tackling festering conflicts and crises, the list of AU challenges is long. 2019 is still young, and there is ample time to get it right. — Robert Malley, President and CEO of International Crisis Group

1. Institutional reforms

Unlike past AU Assembly chairs, who were largely figureheads, Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame energetically pursued his reform agenda and exerted considerable influence over the organisation’s direction in 2018. But there remains much work to be done. Kagame, as the designated champion of reform, should remain actively involved, working with the incoming AU chair Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Commission chairperson Faki, to continue pushing the project forward.

Kagame’s record may well have been mixed, but his efforts in 2018 generated important momentum and produced several concrete achievements. In March, he secured agreement to establish a Continental Free Trade Area, which aims to create a single African market with free movement and a currency union, after more than six years of discussion. Almost 50 countries have signed the treaty, which has so far been ratified by nineteen, just three shy of the 22 it needs to come into force. Although falling well short of his ambitious goals, Kagame’s efforts on organisational streamlining yielded some progress. At November’s extraordinary summit African leaders decided to consolidate the departments of political affairs and peace and security, as well as the departments of economic affairs and trade and industry, bringing the total number of portfolios down from eight to six.

Finally, Kagame successfully pushed for changes that will make the selection process for the Commission chairperson, his or her deputy and the six commissioners, more rigorous, although these changes failed to give the chairperson the power to appoint the Commission’s senior leadership or make them directly accountable to the chair, as originally envisaged.Much work still lies ahead.

Attempts to make the AU more financially transparent and self-sufficient are moving, but slowly. At the July summit, leaders adopted measures to make the AU budget process more credible and transparent by, among other things, providing for finance ministers to participate in the drafting process and introducing spending ceilings. The AU also decided to impose more stringent consequences on member states that do not pay their dues in full and on time, which will be increasingly important as the AU decreases its reliance on donor support.

At the same time, however, only half of member states are contemplating collecting the 0.2% levy on “all eligible goods” imported to Africa, which is supposed to be used to finance the AU, and some are refusing to put it in place at all.Meanwhile, little progress has been made on reforms to bolster the AU’s peace and security mechanisms. Of particular concern is continuing confusion about how responsibility is divided among member states, regional economic communities (RECs), and the AU.

The AU’s Constitutive Act and guiding documents are unclear. However, the principle of “subsidiarity”, which gives RECs the lead on peace and security matters in their respective regions, was explicitly endorsed for the first time by leaders in November, making it almost impossible for the AU to step in when regions reach an impasse on specific crises unless invited to do so.The reform process provides an opportunity to reset the working relationship between the AU and the RECs.

A clear framework for sharing analysis and information should be established and existing mechanisms, such as regular meetings between the PSC and its regional equivalents, should be operationalised. This will build trust between the RECs and the AU, ensuring that regional bodies are more fully engaged in AU efforts on peace and security, and might also help mitigate some of the political barriers to collective action and decision-making.Moves to reform and bolster the PSC have languished. Kagame wanted to ensure that member states sitting on the Council be both committed to and capable of effectively carrying out their responsibilities. He also hoped to review and suggest improvements to the PSC’s working methods.

Those efforts have yet to yield fruit, bumping up against member states’ desire to preserve their own power rather than yield it to Addis Ababa. Optimally, the process undertaken by Kagame would continue with the goal that member states select as Council members only countries that meet the criteria set forth in the PSC Protocol, including a commitment to upholding the AU’s principles, respecting constitutional governance, adequately staffing missions in Addis and New York, contributing financially to the Peace Fund, and participating in peace support operations.

With so much left to do on the institutional reform agenda, Kagame’s departure will be keenly felt, all the more so since the incoming AU chairperson, Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has strongly opposed certain aspects of the agenda. This is in part because Cairo prefers the AU to remain neutral in the continent’s conflicts and crises; it is still smarting from its own suspension from the AU following the 2013 ouster of former President Mohamed Morsi and wishes to reduce the Commission’s influence. Fears that Sisi will seek to reverse progress already made seem exaggerated: Egypt has publicly stated its commitment to continuing the reform process.

2. Burundi

Burundi has been in a state of crisis since President Pierre Nkurunziza’s April 2015 decision to seek a disputed third term in office, which triggered mass protests, a failed coup attempt, armed opposition attacks, targeted assassinations and brutal government reprisals. The government has since engaged in low-intensity warfare against armed insurgents and brutally repressed peaceful dissidents. Violence, rising unemployment, the collapse of basic services and deepening social fractures have forced more than 430 000 Burundians to flee the country, according to UN figures.

A referendum in May 2018, held in a climate of fear and intimidation, approved constitutional amendments that consolidate the government’s rule and open the way for the dismantling of ethnic quotas in parliament, government and public bodies (including the army). These quotas are intended to protect the Tutsi minority and were a key component of the 2 000 Arusha agreement that brought an end to Burundi’s protracted civil war. In short, risks of a violent deterioration are high and the need for external involvement urgent.Yet the AU faces considerable obstacles in this regard. Its role in Burundi waned significantly following the PSC’s failed attempt to deploy a protection and conflict prevention force in January 2016. More recently, relations between the AU Commission and Burundi deteriorated sharply.

On November 30, the government issued an arrest warrant for Pierre Buyoya, a former Burundian president and the AU’s high representative for Mali and the Sahel, accusing him of complicity in the 1993 assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, Burundi’s first president representing the Hutu majority. The same day, the government boycotted the East African Community (EAC) summit, which was due to discuss a report on mediation between Burundi’s political forces. Finally, after Faki called on all sides to refrain from measures “likely to complicate the search for a consensual solution”, government-backed protesters took to the streets of the capital in anger. President Nkurunziza, in other words, appears to be pulling Burundi further toward isolation, shoring up his domestic base and pre-empting any attempt by the AU or the EAC to encourage compromise ahead of the 2020 presidential election.

Such hurdles notwithstanding, the AU will need to try to actively reengage ahead of those elections: urging the government to open political space ahead of the 2020 polls and allow political parties to campaign freely; insisting its human rights observers and military experts be allowed to remain on the ground; and urging the government to sign a memorandum of understanding enabling these AU personnel to carry out their mandate in full. As the polls draw nearer, the AU should steadily increase the number of its monitors and advisers to prepare the ground for a long-term election observation mission.

Given December’s events, the role of the commission and its chair will likely be constrained; intervention will have to take place at the level of heads of state. In particular, the AU should consider resurrecting the high-level delegation it appointed in February 2016 (composed of Ethiopia, Gabon, Mauritania, Senegal and South Africa), or a similar structure, to help build regional consensus on the mediation process and interact directly with Nkurunziza. Alternatively, the AU could encourage the Arusha guarantors (besides the AU, the DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and the U.S., as well as the EU and the UN) to form a contact group, to fulfil a similar mandate.In addition, the PSC should meet regularly on Burundi, especially during the run-up to the elections when the risk of an escalation in violence will be heightened. This, however, will be difficult if Burundi is elected to the Council in February, as expected.

3. Cameroon

Cameroon, long considered an island of relative stability in a troubled region, is steadily sliding toward civil war as the crisis in the country’s two Anglophone regions deepens. Demonstrations in October 2016 against the increasing use of French in the regions’ educational and legal systems sparked wider protests against the marginalisation of Cameroon’s English-speaking minority, about one fifth of the population. The central government’s refusal to acknowledge the Anglophones’ grievances or engage their leaders, coupled with violent repression and arrest of activists, fuelled anger and drove many protesters, who had originally advocated autonomy and improved rights, into the arms of separatist groups.

October’s disputed presidential election further raised political tensions and exacerbated ethnic cleavages: President Paul Biya, in office for 36 years, won a questionable poll in which few Anglophones were able to vote.Around eight separatist militias are now battling Cameroonian security forces and pro-government “self-defence” groups. Since September 2017, fighting has killed at least 500 civilians, forcing 30,000 to flee to neighbouring Nigeria and leaving a further 437 000 internally displaced in Cameroon, according to UN figures. At least 200 soldiers, gendarmes and police officers have died in the violence — more than in the five-year fight against Boko Haram in the Far North — and another 300 have been injured. Separatist casualties number more than 600.

For the most part, the government has signalled its determination to crush the insurgency rather than address Anglophone concerns. In a welcome gesture, authorities released 289 Anglophone detainees in mid-December, but it remains unclear whether the government has had a genuine change of heart: hundreds, including separatist leaders, are still incarcerated. Nor is it clear whether this move alone will convince hard-line separatists to talk rather than fight.

Confidence-building measures are an essential first step. These should include the government’s release of all remaining Anglophone political detainees; a ceasefire pledge from both sides; and support for a planned Anglophone conference, which would allow Anglophones to select leaders to represent them in wider negotiations. These measures could open the way for talks between the government and Anglophone leaders, followed by an inclusive national dialogue that would consider options for decentralisation or federalism.

Yet so far the AU has been surprisingly reserved on the Anglophone crisis, despite the high number of casualties and the danger of wider civil conflict. Cameroon is not on the PSC’s agenda; the Council has accepted the government’s characterisation of the crisis as an internal matter even though it threatens regional stability. AU Commission chairperson Faki visited Yaoundé in July and issued statements condemning the escalating violence, but the severity of the crisis calls for greater and more consistent AU engagement. This will require a proactive approach; indeed, it is almost unthinkable that Biya, a long-time AU sceptic who rarely attends the organisation’s gatherings, will invite it to intervene.Leaders at February’s AU summit could instruct the Council to schedule regular meetings on Cameroon and call on Faki to double down on efforts to bring the parties to the table. They should also call for implementing the confidence-building measures listed above and for beginning a national dialogue. To this end, heads of state should affirm that any obstruction could lead to sanctions against individuals hindering peace, whether government or separatist.

4. Central African Republic

Clashes throughout 2018 in the capital Bangui and a number of major towns illustrate the deadly threat posed by armed groups — a mix of pro-government militias, ex-rebels, bandits and local “self-defence” units — that control much of the country. MINUSCA, the UN peacekeeping force, has failed to neutralise these groups and, as a result, is mistrusted by the general public. Likewise, the national army, slowly being deployed in parts of the country, has been unable to constrain the armed groups’ predatory activities. The humanitarian situation remains dire, with more than one million people internally displaced or fleeing to neighbouring countries and 2.5-million in need of assistance, according to the UN.Russian involvement has complicated dynamics further.

Since the end of 2017, Moscow has been providing the army with equipment and training and President Faustin-Archange Touadéra with personal protection, as well as organising parallel talks with CAR armed groups in Khartoum. The first two such meetings galvanised the AU into restarting its own mediation efforts, which have been stalled throughout 2016, and to persuade Touadéra of the merits of a single, African-led effort. Intense diplomacy, especially by AU Peace and Security Commissioner Smail Chergui, led the AU to convene new talks between the government and armed groups, also hosted in Khartoum.

An accord was signed early February, but still needs ratification. According to media reports, the negotiations led to some agreement on joint patrols and the integration of armed groups into the security forces, as well as on the reshuffling of the cabinet and the inclusion of armed groups’ representatives in the government.In the past, talks held in foreign capitals — involving some but not all armed groups — degenerated in a cycle of broken promises. In contrast, local peace processes held inside CAR, many initiated by religious organisations, have had modest success, easing intercommunal tensions and instituting temporary truces in certain areas. They have also taken some account of armed groups’ political demands while not losing sight of the concerns of local communities in which they operate.

A sustainable political solution in CAR would benefit from a new approach to mediation that involves greater international military pressure on armed groups, and attempts to negotiate with them at the local level where possible. This approach would also recognise that many have local agendas that cannot be addressed without the participation of the local population. To this end, and in the wake of the Khartoum agreement the AU should bring its mediation efforts back in-country and organise separate talks with those parties that have interests in a particular conflict zone, as well as community dialogues aimed at addressing truly local grievances. Ideally, these local initiatives would lead to a second phase of consultations with groups with national claims and ties to regional states, providing a more realistic framework for a program of national mediation.

Chad and Sudan offer backing or safe haven to some insurgent factions, many of whose members originate in these neighbouring countries. Their agreement to cut support and accept the repatriation of fighters will be critical.The September proposal to appoint a joint AU-UN envoy appears to have been shelved. If so, a structure nonetheless should be put in place to build consensus between Bangui and key regional governments, chief among them Chad and Sudan, with the aim of securing buy-in to the AU-led mediation and reducing support from neighbouring countries to insurgent groups in CAR.

5. Democratic Republic of Congo

A political crisis erupted in the DRC in the wake of last December’s presidential race. The election pitted Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, outgoing President Joseph Kabila’s preferred candidate, against two opposition leaders, Félix Tshisekedi and Martin Fayulu — the latter supported by Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moïse Katumbi, political heavyweights barred from contesting the vote. Although official tallies gave Tshisekedi a narrow victory, a parallel count by the Congolese Catholic Church confirmed by leaks from the electoral commission indicated that Fayulu had won by a landslide. The clear implication was that Kabila and his allies had rigged the results in favour not of their initially favoured candidate — whose victory would have been met with incredulity and would have united the opposition — but of the opposition candidate they found more palatable. In response, Fayulu filed a challenge with the constitutional court, the DRC’s highest.Initial reactions by most African and Western diplomats were muted. In stark contrast, an ad hoc meeting of African leaders assembled by AU Chairperson President Kagame, issued a surprisingly bold statement on January 17.

Besides raising “serious doubts” about the provisional results, it called for suspending the proclamation of final results and announced the urgent dispatch of a high-level delegation to Kinshasa to help defuse the post-electoral crisis. Kinshasa acted quickly to pre-empt any such action: in a snub to the AU and Kagame, the Constitutional Court refused to delay its decision and rejected Fayulu’s appeal, thereby upholding Tshisekedi’s purported win. SADC (the Southern African Development Community) together with several regional leaders, including some who had appeared to support the AU statement, quickly recognised Tshisekedi’s presidency. The AU cancelled the planned high-level visit, taking note of the court’s ruling and signalling its willingness to work with the new government. The rest of the international community soon followed suit.

The episode was damaging to the AU. To begin with, its failure to halt the Congolese election’s manipulation raised further doubts about its ability to uphold electoral and governance standards. For the PSC, Kagame’s decision to bypass this organ in favour of a seemingly random gathering of leaders called the Council’s authority into question. But the greatest damage would be to the continent as a whole if the AU, chastened by this embarrassment, were deterred from acting in future situations of this type, giving autocratic regimes an implicit green light to continue to rig elections with impunity.Even in the DRC itself, the AU’s role is not over.

This highly controversial background aside, the new president and government have a responsibility to focus on stabilising the country and avoid spill-over from internal conflicts affecting the rest of the region. Of course, Tshisekedi will have to work with Kabila, who enjoys a large majority in the newly-elected parliament. But AU leaders should strongly encourage Tshisekedi to demonstrate his independence from the former regime and reach out to Fayulu as well as his supporters to build a broad-based coalition. The PSC in particular ought to keep the DRC on its agenda, as unrest in the East is likely to worsen, which could also exacerbate already serious tensions among Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi.

6. Somalia

The federal government of Somalia’s manipulation of December’s presidential election in South West state is illustrative of a raft of unresolved tensions in the country, particularly between the federal government and member state governments. It is also likely to sow further instability. After multiple delays, the government held the controversial poll, and Abdiasis Mohammed “Laftagareen” a former member of parliament and minister, won. His victory was secured when Mogadishu ordered the arrest of his popular Salafi opponent, Mukhtar Robow “Abu Mansur”, a former Al-Shabaab leader, and deployed Ethiopian troops in key towns to suppress the resulting dissent.

In doing so, the federal government took a significant risk: that of alienating Robow’s huge clan constituency, inflaming anti-Ethiopian sentiment and signalling to other Al-Shabaab defectors that relinquishing their struggle could land them in prison. Most important, Mogadishu has thrown away an opportunity to build a local power-sharing model with a conservative Islamist who could potentially be a bridge to the Salafi community and undercut support for the Al-Shabaab insurgency.

The crisis in South West state exemplifies President Mohamed Abdullahi “Farmajo” Mohamed’s determination to check the power of regional politicians. It also is a manifestation of his government’s increasingly centralising tendencies, of which Crisis Group previously warned. The subsequent decisions to expel Nicholas Haysom, the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Somalia, for questioning the legal basis of Robow’s arrest, and to execute a number of Al-Shabaab prisoners, play well with Farmajo’s base but do little to advance the country’s stability. Gains made during the last eighteen months — including agreement on the Roadmap on Inclusive Politics, adoption of the National Security Architecture and commitment to the Somalia Transition Plan — risk being undermined or reversed.The AU has taken a security-focused approach to Somalia since AMISOM, the AU’s peace enforcement mission in Somalia, was first deployed in January 2007.

This in turn has limited the organisation’s ability to effectively contribute to a lasting political solution to the conflict. (The UN Assistance Mission in Somalia, UNSOM, has managed the politics to date.) The planned drawdown of AMISOM forces, which is supposed to be completed in 2020, makes it all the more imperative to strengthen the political dimension of the AU’s engagement to ensure territorial and political gains achieved by the use of force against Al-Shabaab are not lost. The PSC has acknowledged the importance of the undertaking, calling on the Commission in a February 2018 communiqué to “ensure a coherent and unified political approach on Somalia”. The AU is coming late to the party, however, so any political strategy it develops should complement not duplicate those in existence by taking into account the division of labour between the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the AU and the UN, as well as Somalia’s bilateral partners. It should also clearly identify and build upon the AU’s comparative advantages, which include AMISOM’s access to wide areas of the country off-limits to the UN and other partners, as well as its potential to be a more neutral arbiter within the region.

7. South Sudan

2019 offers hope, however fragile, for a reduction in fighting in South Sudan, following five years of brutal civil conflict in which some 400 000 people have died and nearly four million have been displaced internally and externally. In September 2018, President Salva Kiir and his main rival Riek Machar, the former vice president-turned rebel leader, signed a power-sharing agreement. Violence has subsided and, for now, that is reason enough to support this fragile accord.

The deal, brokered by Presidents Omar al-Bashir of Sudan and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, the regional leaders with the most at stake in South Sudan, is not a final settlement to the war. But it opens the door to a new round of fraught negotiations that could lead to a unity government and, eventually, elections.There are abundant reasons for scepticism. This new pact builds on a previous deal, concluded in August 2015, which collapsed less than twelve months after it was signed, triggering a surge in fighting.

By calling for elections in 2022, the agreement perpetuates the Kiir-Machar rivalry and risks yet another violent showdown. Worryingly, security arrangements for the capital, Juba, have yet to be finalised, as have plans for a unified national army. In addition, donors, tired of financing failed deals, are waiting for concrete action by Kiir and Machar before committing funds. The U.S., the long-time driver of Western diplomacy in South Sudan, has stepped back.This caution and broader cynicism are understandable, given the parties’ track record and the fact that they squandered billions of dollars in past donor support. But momentum is being lost, and if this deal fails the country could plunge back into bloody warfare.

Although the AU took a back seat in South Sudan from the outset, essentially supporting mediation efforts of the regional bloc IGAD, it has an important role to play going forward. The high-level ad hoc committee on South Sudan — composed of Algeria, Chad, Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa, and known as the C5 — forms part of the body tasked with finalising the formation of regional states, the number and boundaries of which are disputed. Building consensus on this politically sensitive and highly technical issue will require consistent engagement from the C5 heads of state, who would be well advised to draw on support from the AU Border Program and partners with relevant expertise.

The new accord is supposed to be guaranteed by a region that itself is in flux – alliances are shifting following the rapprochement between Ethiopia and Eritrea – and that does not agree on what form a lasting political settlement should take or how to reach one. By stepping up their engagement on South Sudan, the C5 and PSC could help keep regional leaders focused on ensuring that the deal does not disintegrate and encourage them to begin building consensus for a wider settlement that shares power more equitably across South Sudan’s groups and regions.

8. Sudan

Anti-government demonstrations have engulfed towns and cities across Sudan since mid-December 2018, when the government ended a bread subsidy. Security forces have killed dozens in a crackdown that could intensify further. President Omar al-Bashir, in power since 1989, has survived past challenges to his authority by resorting to brutal repression. But the scale and composition of the protests, coupled with discontent in the ruling party’s top echelons, suggest that Bashir has less room for manoeuvre this time around.

Beyond the immediate humanitarian costs, significant bloodshed would undermine Sudan’s incipient rapprochement with the West, scuttling future aid or sanctions relief, thereby deepening the country’s economic woes.The AU’s first priority should be to minimise violence against demonstrators. African leaders with influence in Khartoum should publicly warn against the use of deadly force and call on the government to keep the security forces in check. Behind the scenes, they should encourage Bashir to step aside and provide incentives, such as guaranteeing asylum in a friendly African country, for him to do so. If necessary to facilitate a managed exit, they should work with the UN Security Council to request a one-year deferment of the International Criminal Court’s investigation of him for atrocity crimes during the counterinsurgency campaign in Darfur.

This article was originally published here.