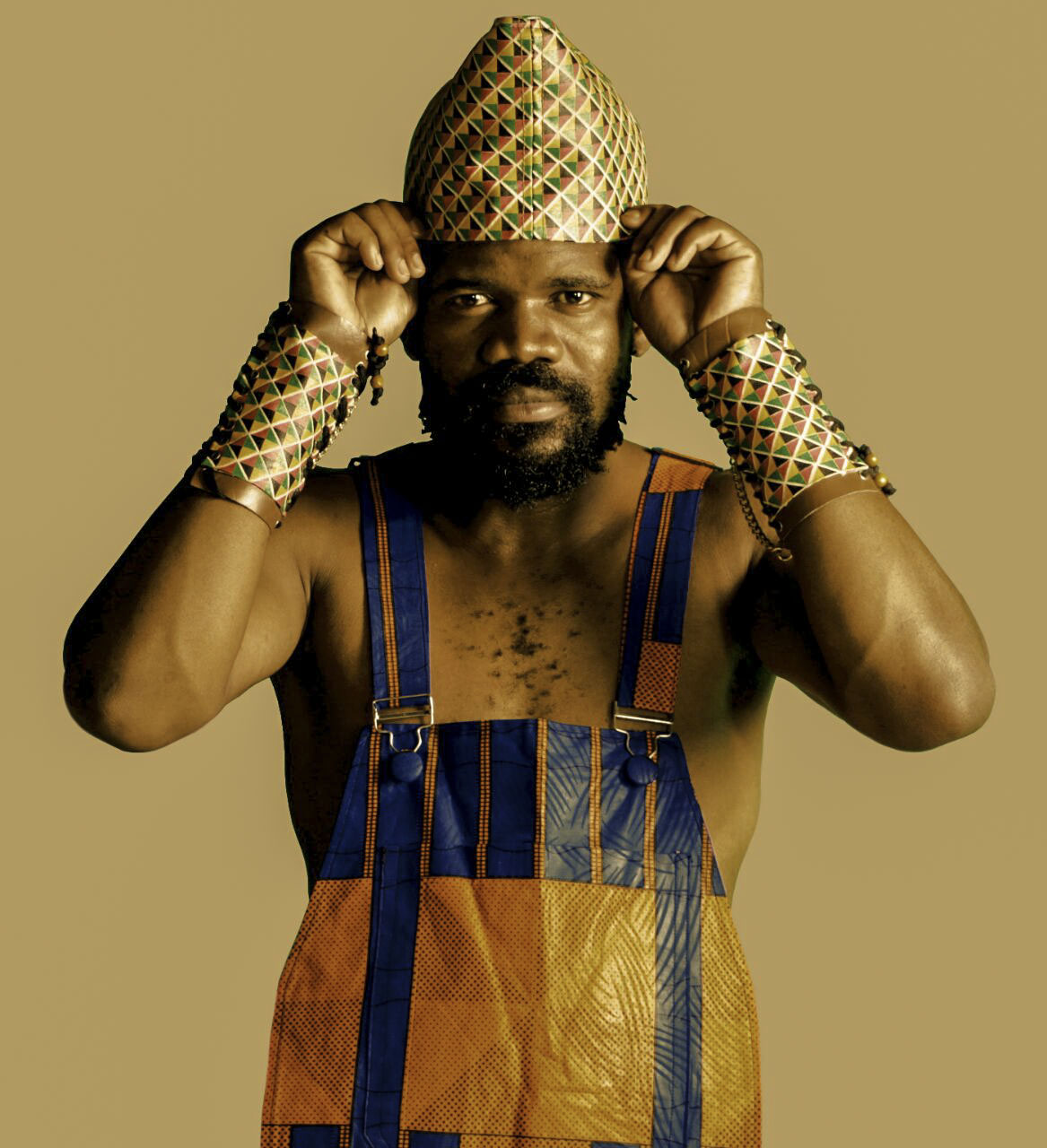

Mountain man: Morena Leraba is the fantastical alter ego created by Teboho Mochaoa, derived from his Sotho culture and used to convey his frustration with the political situation in his country. Photo: David Harrison

When gun-toting Boers were threatening to usurp Lesotho from its rightful inhabitants during the rampant wars of the 1800s, Morena Moshoeshoe I sought Queen Victoria’s might of Empire for protection. A treaty was signed in December 1843 that declared the country a British protectorate under the direct rule of George Thomas Napier, then-governor of the Cape Colony.

By 1868, owing to mounting pressure from Boers who’d already annexed sizeable chunks of arable land in the Free State-Basotho War of 1858 — Britain had subsequently reneged on its side of the 1843 accord — the country appealed to Victoria directly. Basutoland was declared a protectorate, but on paper; it was a colony in its make-up, character, and all else.

In 2016, this history wasn’t lost on two Basotho men when they pounded the tarmac of Cape Town’s city centre with coordinated, syncopated steps. With the seawater-flavoured stench of the colony looming large, and the movement for the return of stolen Basotho land gaining momentum in their country, the discussion between them — one was Teboho Mochaoa and the other myself — became an exchange about the political conditions that were raising Basothos’ anxiety since the military coup of August 2014.

The things they thought bad about their country then are worse now: tumultuous government relations, petty inter-party politics, increased murders of musicians in the accordion music fraternity.

Morena Leraba, Mochaoa’s mask-donning, blanket-wearing, fighting stick-carrying and gumboot-decorated alter ego, is fluey when I contact him to set up an interview. Later in the day, down a Skype line that creates impractical lags on a faulty wi-fi connection at critical moments, he feels rested enough to attempt a succinct version of the key events that have culminated in the rampant activity of the past two years. They are as meandering as the genre-hopping tendencies he exhibits.

Famo roots

At the core of his approach is famo, Basotho’s traditional, accordion-led music. Pinning down his sound or finding a name for it is as slippery a process as descending the Lesotho mountains he grew up surrounded by. He said, about two years ago, that infusing, say, electronic music into that accordion music framework “is just a term” and that he was “just going with the waves”.

He caught the frequency of the all-mighty BLK JKS while surfing these waves. The connection came through drummer, producer and deejay Tshepang Ramoba, with whom he did a few Lesotho-side gigs before meeting the rest of the band. Leraba did not know about the boundary-breaking quartet prior to the road trip he and Ramoba made to the Maloti Mountains. His reaction to hearing their sound? “I was, like, holy shit!” he recalls.

The band’s debut opus After Robots features a portrait of a mask-clad, grey blanket-wearing Mosotho shepherd made by Nigerian photographer and filmmaker Andrew Dosunmu. The band didn’t know at that point that they’d one day feature the morphology of that shepherd figure during their set at the inaugural leg of Afropunk Joburg in 2017.

Neither did Leraba, whose aesthetic derives from life as a shepherd. He would have been trappin’ in the gallows at that point, ruminating on the future with homies like Kommanda Obbs while blazing potent mountain herbs phans’ komthunz’ welanga, dreaming about being in a band and touring far-off lands such as Europe.

Rap meister: Kommanda Obbs, creates magic music with Morena Leraba. Photo: The ArtKartel

Leraba says he met Kommanda Obbs (real name Obatia Chapi) through a mutual friend in “maybe 2010”. Obbs was a rising star on Lesotho’s rap scene at that time, having just released his definitive long-player Ts’epe. The album took boom bap beats and sent them on a 16-bar roll with the hard-edged lyrical flair of famo musicians, using as rich a range of metaphors and as deep a love for linguistic precision as the progenitors from which it drew. Leraba, on the other hand, hadn’t been conceived; there was just Teboho, a design student with no rapping aspirations whose vision was in lock-step with Obbs’s.

D2amajoe

Beyond shared passions and a grand vision to turn D2amajoe — a loose collective of emcees, designers, photographers and other creative vagrants from Lesotho and parts of the Free State — into a distinguished pan-African brand was a love for famo, and of Famole in particular, whom Obbs regards as the greatest unknown poet-lyricist-musician.

A student of Mants’a, the late Famole took famo and imbued a sense of urgency into it by using his poetic gifts to broach subjects such as the rand’s value in comparison to the American dollar and the British pound (Ranta e Oele); factional party politics (Chaba sa Qabana); and the excruciating pain experienced when a loved one transitions (Lefu la Ntate).

Famole captivated minds and captured the zeitgeist of an entire generation, much like the better-known Sankomota had before him.

“[They] also played a huge role, [especially] coming from Lesotho. It wasn’t really a given, it was a challenge for artists. Speaking for myself, I can literally count [on my fingers] the legends who are known to the rest of the world, or at least South Africa, from Lesotho,” says Obbs about the Frank Leepa-led supergroup that can claim the likes of Ts’epo Ts’ola and Budhaza as alumni.

“[I respect them] because they were able to push the envelope and crack it without resources and connections. They attracted those as they went on.

“I personally don’t consider rap a talent. Anyone can rap,” states Obbs. He draws from traditional Sesotho music for this reason. “That’s how I ended up being the artist that I am today.” He opened for Damian Marley during the dancehall don’s two-city tour, and played at La Réunion’s Sakifo Musik Festival in 2018.

While seeking to connect these disparate worlds, populated by rapcats including Obbs and Leraba (and Skebza D and Papa Zee and Boshoa Bots’oere, etcetera) on one side and Famole, Mants’a, Rants’o, Sanko and Mahlanya on the other, I spoke to radio broadcasting vanguard Tello Leballo, known to his legion of listeners as Dallas T, who gave these rap cats (bar Papa Zee) breakthroughs on his radio platform.

For the full New Accordion Cowboys playlist click here.

“It’s a scene that introduces a new phenomenon of approaching music in our epoch, which solicits more creative diversity and [an] inordinate sense of cultural belonging,” he said.

Leraba, born in the southern Lesotho district of Mafeteng, cites Sanko as his chief influence. The late musician was one of the first famo artists to release and distribute his music independently.

“Mahlanya is today’s Sanko. He’s omnipresent. His music plays in taxis on my way home, and on my way to Joburg. But my biggest influence, currently, in terms of writing, style and imagery, is [Khafetsa]Likhau from the district of Mohale’s Hoek,” he says.

Initially an affiliate of Mahlanya’s Seakhi movement, Likhau has since gone off to run his own operation, but still retains the litsamaea-naha spirit of song that has turned his once-associate into somewhat of a demigod among famo adherents.

D2amajoe associates Sneiman and Koete Sekhukhuni take their image seriously. In the video for Shoeshine le Manothi, the two can be seen rocking Pringle jerseys, Brentwood pants, Florsheim shoes, and seana-marena blankets — items associated more with famo artists than they are with vernacular rappers who flex rhymes over trap and hardcore hip-hop beats.

Sacred medium

Concerning Leraba’s progress, Dallas T says: “[His] moves have proved beyond doubt that music is a sacred medium that speaks to all without a need to interpret linguistically. His love for a ripe and rich culture compelled him to push his message beyond borders and beyond measure. This goes to show that, with music, artistic devotion and dreams chased fearlessly — of course amplified by the right amount of talent — all can be achieved.”

Indeed, all can be achieved, but what happens when an artist gives their all to a project, only to have someone else fuck up its upward-trending trajectory? Such was the case with Obbs’s self-titled sophomore long player, which he released on bra Sipho Sithole’s Native Rhythms Productions label.

He’d said about that album, prior to its release, that it was “telling the African story”. He elaborates: “The same way people know about Sankomota, I believe this is the kind of album that people can take from. It represents beyond Sesotho; it represents the continent.”

But Native Rhythms, in partnership with Universal Music Group (SA), appeared clueless about how to package and distribute the music. There was little traditional marketing: no press run leading up to the album release, no video and no national or regional tour post-release. Non-traditional marketing didn’t feature either: no paid-for Instagram and Facebook posts, no prominent feature on Apple Music’s front store when the album was released in May.

Leraba is back in Cape Town in 2019 to perform with his band at the Cape Town Electronic Music Festival.

“I’m afraid BLK JKS is dying slowly,” he had said earlier in the week.

Ramoba is focusing on his deejaying and his POSTPOST production house, and Mpumi Mcata is exploring the medium of film. Molefi Makanise still plays with Leraba’s band, which now features the electronic fingers of Vox Portent and Mpho Molikeng’s ancient percussion.

Leraba says he is still catching waves, but is more confident about his direction this time around. Makananise’s pounding bass licks are reminiscent of the distinctive, midrange-decked famo basslines, and Molikeng’s percussion recalls the ancestral bothuela (diviner) grooves that rouse Leraba’s vocal range unto levels where he’ll growl, chant, spit, as well as sing over Vox Portent’s sublime LFO dubs.

He’s also been touring and collaborating. Names such as Spoek Mathambo and Damon Albarn fall off his tongue, and festivals such as Oppi and Endless Daze locally and overseas-based mcimbis such as France’s Les Rencontres Trans Musicales and Eurosonic Noorderslag Festival Groningen in the Netherlands know well the might of his stage presence.

So how do we refer to this new breed of artists who draw directly from famo?

Obbs calls his sound ts’epe, Leraba still isn’t sure and Dallas T thinks it can be called anything.

“It’s [not] the call of the creator and [the] artist in question to categorise, since the whole inception process was conducted by such. What matters is the originality, creative input and substance,” he says.