(John McCann/M&G)

Increasing demands by failing state-owned enterprises, rising debt servicing costs and an ever-expanding public sector wage bill have left the government in a tight fiscal position but, despite this, the state forgoes more than 4% of gross domestic product (GDP) because of preferential tax expenditure.

This is tax relief provided by targeted exemptions, deductions or credits. This is also used to encourage taxpayers to undertake activities prioritised by the government, such as socioeconomic development.

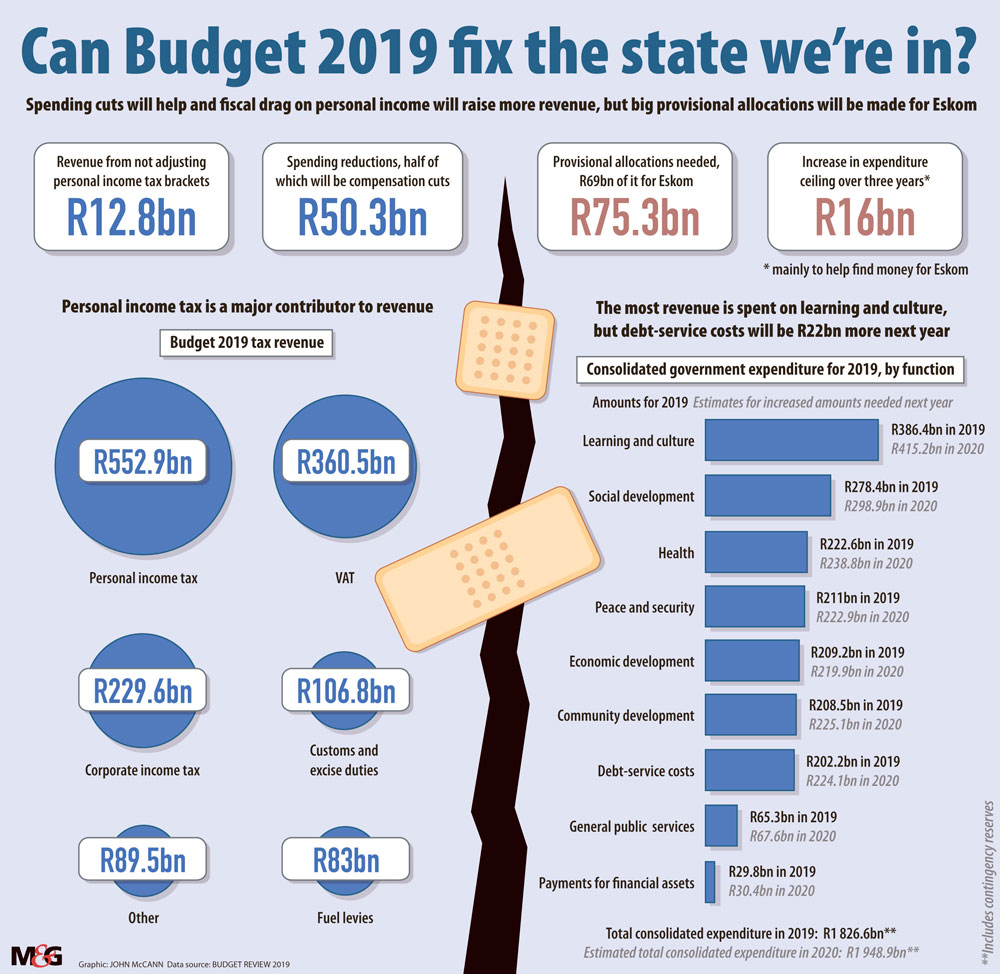

According to the 2019 Budget Review, for the most recent figures available, this amounted to about R209-billion in 2016-2017, or 4.7% of GDP, and should amount to about 16% of the total R1.3-trillion expected to be raised from tax this year.

In 2016-2017, tax exemptions on pensions accounted for the largest amount — R72-billion; zero-rated goods amounted to R56-billion; and R28-billion went to the development of the motor vehicle industry.

In the 2018-2019 financial year, weak economic growth accounted for an estimated R8-billion shortfall in personal income tax because of job losses, low wage settlements and reduced bonuses.

There was a shortfall of about R12-billion in corporate income tax, largely because of reduced production in mining and quarrying and an underperforming financial sector.

Given that there have been substantial tax increases over the past four years, the treasury did not increase tax in any category to limit the negative effect on economic growth, but personal income brackets were not adjusted for inflation, which would make for increased tax collection as salaries increased.

“Since 2015-2016, measures have been introduced to raise additional amounts of R16.8-billion, R18.1-billion, R28-billion and R36-billion per year,” according to the document.

But other things are eating into government revenue. For one, the document noted that “higher diesel refund payments to electricity generation plants and primary producers, such as farmers and mining companies, have slowed fuel levy collections”.

Michael Sachs, a former head of the budget office at the treasury and an economics lecturer at Wits University, told the Mail & Guardian that if the government wanted to increase its take on corporates income taxes it could relook at rebates.

“It’s not only about changing the headline [corporate tax] rate of 28%, but you can also actually get more revenue from big corporates in South Africa by changing those rebates. If treasury wanted to act on the corporate income tax side that’s where they would look,” Sachs said.

The budget document states that the government continues to monitor and evaluate tax incentives to prevent wasteful spending.

Sachs explained that the level of scrutiny as well as public engagement with and transparency about tax expenditures was not equal to that given to government spending, even though the effect on the budget was the same.

Mike Teuchert, Mazars’s national head of taxation, echoed this and said, if the government did limit the rebates, it would have to weigh against stimulating economic activity. For example, the Motor Industry Development Programme had stimulated the economy and created jobs.

“Those are very directed and, if you are going to look at a specific industry and you have done your research, the incentive itself will pay for itself, in a way. You will make an investment and get a return on investment,” Teuchert said.

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust business journalist at the Mail & Guardian