We are not doing anywhere near enough to train all the adults in our childrens lives in how to help children develop grit, curiosity, self-control, social intelligence, zest, optimism and gratitude, the writers say (John McCann)

COMMENT

On a freezing late January afternoon in New York, forum members of the International Education Funders Group met behind closed doors to ask: “Is social and emotional learning a necessity or a nice-to-have in Africa?”

Africa has diverse challenges from school to school, let alone country to country, so perhaps the question was rhetorical: where education has succeeded in poor areas in other parts of the world is where social and emotional learning is prioritised. In other words, education is at least as much about how we learn to navigate the world inside our heads as it is about how to understand and operate in the world around us (where maths and languages are useful, for instance).

The KIPP Charter Schools in the United States, which serve low-income pupils from preprimary school to high school, believe in “51% character, 49% academics”. A study by Western Michigan University and Columbia University Teachers College in New York (as cited by the Public School Review) shows that the stellar graduation rates in KIPP schools are because of this teaching methodology. KIPP’s focus on character has resulted in a sizable and statistically significant effect on reading and maths achievement — increases of between five and 10 percentage points (compared with the control group).

Understandably, in South Africa the current focus is on assessments and the drive to get children to read for meaning, not “character”, at least not at the level of national debate.

On January 19, educationist Nic Spaull met Finance Minister Tito Mboweni to talk about what’s truly going to reform our education system. In a background note published on his website, Spaull argues that half of South Africa’s primary schools are “cognitive wastelands” because 45% of grade 4 classrooms did not have a single pupil who could read for meaning.

Moreover, although there is the huge build-up to and hullabaloo over the matric results each year, the real crisis is this: 60% of children who start school will reach and write matric, 37% of those matric candidates will pass and only 12% of those will go to university. Four percent of those students will complete an undergraduate degree in six years. (An article for another day is the rising global return to post-secondary education and the contentious debates about why this change has happened and is accelerating, even as we question the value of some kinds of tertiary education on the eve of the fourth industrial revolution.) Spaull points to weak foundations in primary school as the root cause and suggests interventions such as the fiscal prioritisation of primary school, a national primary school assessment and the so-called Ramaphosa Reading Plan.

This article is not dismissing these suggestions. But what’s missing is the notion of success using noncognitive means, aided by the quality of the relationships between children and their caregivers, and the messages they receive from their home and school environments.

There’s a lack of awareness about the science of how we learn to navigate our worlds. The psychology of attachment, for instance, looks at how the quality of care in our early childhood helps us to develop the noncognitive skills and physical brain growth needed for lifelong success. Such capabilities, according to author Paul Tough, include grit, curiosity, self-control, social intelligence, zest, optimism and gratitude.

These can’t be taught per se, but they can be modelled by a present and conscious adult in a child’s life. The “third teacher” is also important — this is the classroom and wider school environment. These should be welcoming, community-oriented and have plenty of opportunity for play and exploration.

We are not doing anywhere near enough to train all the adults in our children’s lives in how to help children develop grit, curiosity, self-control, social intelligence, zest, optimism and gratitude. This is not an easy task: our children are complex. Their inner worlds continue to be shaped by systemic racism and sexism and internalised oppression.

Furthermore, South Africa is a violent place. A recent study led by Linda Richter at the Centre of Excellence in Human Development showed that, of the cohort studied, only 1% of children had never experienced violence. Violence was frequently experienced at home, in schools and in the community. Of those who reported exposure to violence, half said they suffered it at home.

Tough noted in a New York Times article that “the part of the brain most affected by early stress is the prefrontal cortex, which is critical in self-regulatory activities of all kinds, both emotional and cognitive. As a result, children who grow up in stressful environments generally find it harder to concentrate, sit still, rebound from disappointments and perform well in school.” In other words, “when you’re overwhelmed by uncontrollable impulses and distracted by negative feelings, it’s hard to learn the alphabet”. In poorer communities, parents are overburdened and overwhelmed, making responsive parenting difficult.

It’s in this context that the Tomorrow Trust has pinpointed the need for holistic education. Our Saturday and holiday school programmes are being redesigned to focus on relationship and pedagogy, so children gain a sense of belonging, and experience the thrill of overcoming a challenge, whether that be a maths quiz, speaking in front of the class or building a robot.

Although Spaull talks about the need for better training and for improved pedagogy, we must use what is already there, our innate urge to connect. Teachers are no different. What about channelling resources into self-development and care workshops for teachers? Before you think this concept belongs in a self-help manual, consider that the creation of safe spaces in the classroom is conducive to brain development and, consequently, to optimal learning.

Educators, skilled in their own self-management, facilitate the development of noncognitive or “character skills”. By helping pupils and students to find their identity, meaning and purpose in life, we radically increase their likelihood of academic and life success. The trick is: you cannot teach character but you can create the environment and model the behaviours that do.

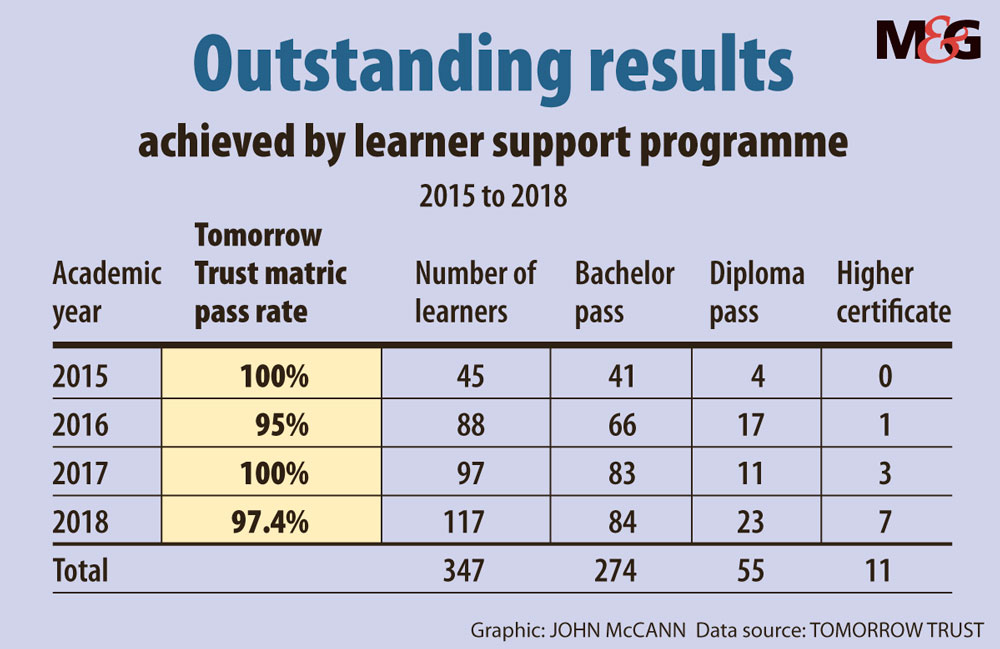

The Tomorrow Trust has shown that academic persistence and grit can be developed by helping vulnerable and orphaned young people to feel that they belong and by giving them opportunities to take risks, and to experience failure and success. We believe that personal growth emerges from a combination of pressure and support.

All South Africa’s children experience daily pressure in spades. We need to learn how to ensure adults can support them. The Tomorrow Trust does this by using “regular” government educators who work on weekends and in holidays. These teachers have extra support from our recent matriculants and university alumni, as well as educational psychologists.

Although we adhere to the national Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements and have done things “by the book”, the most critical component of our success is the character-building work. In all our lessons, we weave in participation, assertiveness, communication, empathy, decision-making, conflict resolution and critical thinking. We always focus on mental health, personal responsibility and lifelong learning and borrow from Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck’s idea of the growth mind-set. The latter leads to a person embracing challenges, persisting despite adversity and finding lessons and inspiration in the success of others.

Our pupils are referred to us by the Gauteng department of social development as orphaned and vulnerable, and are failing most subjects by large margins.

For example, our top learner for 2018, Sipho Thanjekwayo, achieved an 87% average. In 2015, he was selected to join the holiday and Saturday school programme. When he joined us (he was in grade 10), he was averaging 54%. He has now passed his National Senior Certificate, and obtained a bachelor pass/university entry and received distinctions in maths, English, life sciences, physical science and accounting.

Sipho is now enrolled to study accounting at the University of the Witwatersrand this year.

To help our children to finish school and to be productive members of our society requires love and care from adults early on. No amount of reading instruction and national assessments are going to create the spaces conducive to learning if we don’t have the foundation of connection. We need to be deliberate as a society about achieving emotional indicators alongside physical indicators or academic measures.

James Donald is the chief executive of the Tomorrow Trust and Beth Amato is a writer specialising in human development