(John McCann/M&G)

Edcon chief executive Grant Pattison and his team achieved what many critics doubted they could — secure an almost R3-billion lifeline for a retail company that is deep in the doldrums. But that, analysts argue, may have been the easy part.

The herculean task, as it is described by one analyst, is going to be keeping the Edgars, Jet and CNA brands afloat in a rapidly changing retail environment. Plus there is now R1.2-billion in deferred workers wages from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) in the game.

Late last Friday, thanks to a blend of commercial self-interest on the part of participants and an acute concern about possible jobs losses, the group announced it had secured the R2.7-billion in cash it needs to keep going for another two to three years.

The money was corralled from existing lenders, landlords exposed to Edcon and the UIF, through its asset manager, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC). The deal included new cash commitments and rental reductions and leaving Edcon free of interest-bearing debt.

The UIF has R1.2-billion invested in Edcon. The fund, which pays out unemployment benefits to workers who lose their jobs, had about R156-billion in surpluses, according to the PIC’s latest annual report.

The UIF’s investment policy allows for up to 20% of assets under management to go towards “socially responsible investments, which have a high social impact, while yielding a reasonable investment return”, its spokesperson, Makhosonke Buthelezi, says.

In addition, under a recent amendment to the Unemployment Insurance Act signed into law in 2017, the UIF is empowered to finance “the retention of contributors in employment” — in other words, to fund the keeping of workers who contribute to the UIF in their jobs.

Furthermore, the preservation of 38 000 jobs at the Edcon Group and 100 000 indirect jobs at downstream suppliers and manufacturers will save the fund about R2-billion in potential unemployment insurance claims, Buthelezi says.

“It is the view of the UIF board that the proposal presented by the Edcon group will preserve jobs and facilitate the immediate retention of many UIF contributors in employment and that, if ignored, it would be a cumbersome process to re-introduce the contributors back into employment, given the economic conditions that prevail at the present moment,” he says.

The PIC, which manages the money on behalf of the UIF, did not respond to questions but no doubt its wider portfolio of assets have been helped by the Edcon rescue.

Along with the UIF’s money, the PIC manages about R1.8-trillion for the Government Employees’ Pension Fund (GEPF). As part of its assets under management, the PIC manages about R45-billion in unlisted property for the GEPF, representing a gross lettable area of more than 1.2-million square metres. About 56% of this portfolio is exposed to the retail sector.

With Edcon, one of the largest non-food retailers in the country, which occupies about 10% of mall space, its collapse would have implications for the property sector, not to mention the GEPF’s portfolio.

Nishlen Govender, a portfolio manager at Citadel, says Edcon’s landlords have avoided a significant vacancy risk at a time when investors are becoming increasingly concerned about vacancies and rental increases in an embattled retail and office sector.

“Under the circumstances, this type of deal is as good as it could get for the property companies,” he says.

But Govender is not convinced that saving jobs and averting higher vacancy rates in the short term will benefit the UIF and property companies in the long term.

“Yes, in theory, injecting funds into Edcon will avoid an event that could lead to significant payouts but this investment will now become a balance sheet issue for the UIF. For instance … will it need to be impaired should Edcon face further issues down the line? If the Edcon business is structurally in decline, will the investment require further inflows of capital from the UIF?”

The complexity of the issue could become immense, he says, moving “from a once-off payout to a multiyear investment decision with no guarantee of returns”.

The cash injection shifts the problem from a significant South African business and its effect on local suppliers and property companies to the UIF, the PIC and the balance sheets of the property companies.

“In a way, this is merely kicking the can down the road without dealing with the issues at hand,” Govender says.

But independent retail analyst Syd Vianello says the deal has bought Edcon time. It takes about six seasons, or three years, to turn a retailer around, and the deal enables Edcon to do this.

“Pattison and his team have their work cut out for them but there is no reason they can’t do it,” Vianello says.

In an interview on 702, Pattison said that, to secure the money, he had to prove that the turnaround at Edcon is already under way. The company had for some time been steadily rightsizing its business by reducing floor space and renewing its focus on its core brands, namely Jet, CNA and Edgars, as well as its ThankU services programme, which houses its credit, insurance, loyalty, cellular and e-commerce offerings.

Credit to customers is an integral part of the ThankU offering. In 2012 it sold its credit book to ABSA, but Edcon has since started a “second-look” or internal book which is able to provide credit customers that might have been rejected by ABSA.

According to the company credit has always been and remains a big part of the group business as loyal credit customers tend to spend more with Edcon, and do it more frequently than cash customers.

But each Edcon brand faces competition on several fronts. Edgars is competing with a range of new international entrants such as Zara, H&M and Cotton On, not to mention several local competitors.

The Australian Cotton On brand also houses stationery shop Typo, which faces off against CNA, and count fashion retailer Jet plays in the same arena as the likes of Ackermans and Pep.

Nevertheless its slow reorganisation is beginning to yield results, Pattison said, and CNA, for example, had increased stationary sales by between 10% and 15% on the previous year despite an 18% decline in space. Edgars, meanwhile, had made more profit in the past four months than it did in the previous year.

Jet — a large division that included the Jet Mart offering, which sold food, appliances and crockery — was still being restructured to return to the straightforward Jet format.

“We are busy still restructuring [and] changing the shape of that business so I am hoping from April onwards it will turn,” he said in the interview.

The deal releases Edcon from the R8-billion debt it was saddled with after it was delisted in a highly leveraged private equity transaction by Bain Capital.

Years of paying off interest has meant that Edcon had steadily reduced its headcount to the point that it was understaffed, said Pattison. This had meant that, because it had reduced the size and number of its stores, the group had been able to relocate staff to surrounding ones, increasing the number of staff per store but keeping the headcount relatively stable.

“I take my hat off to Grant Pattison; he’s got a herculean task,” says Fairtree Capital portfolio manager Jean-Pierre Verster.

The number of stakeholders involved is an indication of how important it is to ensure an “orderly and managed” reorganisation of the company, Verster says.

But he is not convinced that Edgars will exist in its current format in three years’ time.

“I’ll be very surprised, for example, if CNA exists with the group,” he says, by way of example. But Jet is the most likely to survive in some shape or form in the coming years.

But, Verster says, should Edcon’s turnaround fail and its “breathing room becoming constricted again”, it could well become a target for competitors, who will simply wait to pick up a distressed asset.

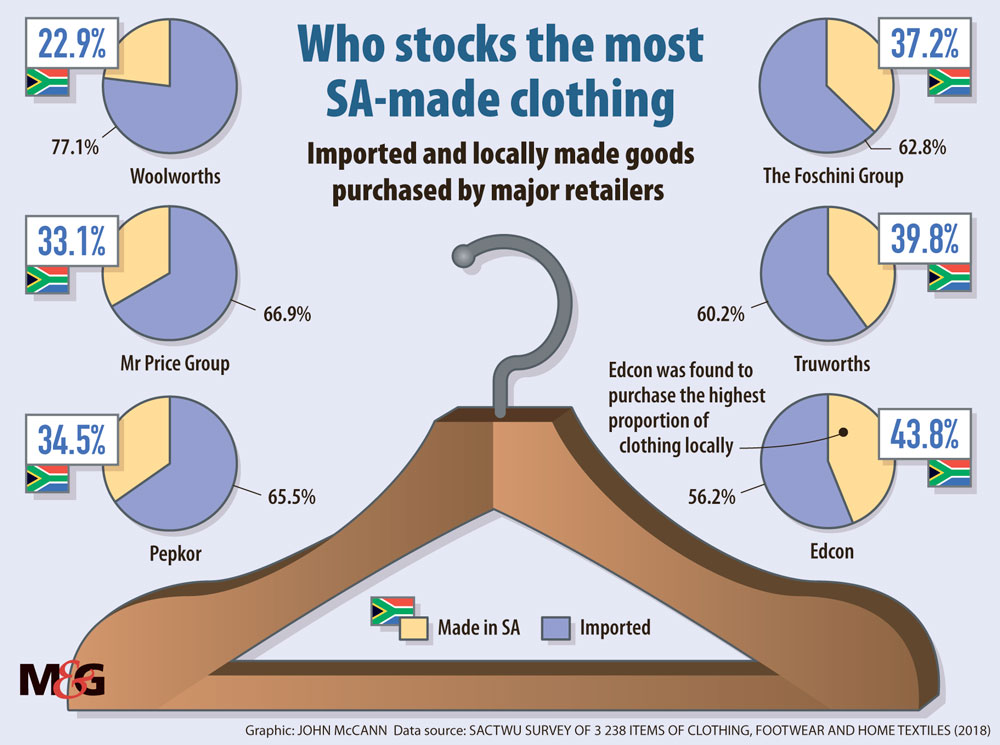

According to the South African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union, Edcon buys the largest amount of locally manufactured clothing and textiles (about 44%), so it has bought local manufacturers some additional breathing time too.

“Research has shown that South Africans do care about the production of their goods and will buy locally produced goods,” says Govender, adding that, outside of the investment, few South Africans know about Edcon’s extensive South African supply chain. It could give the company a competitive edge but it has yet to be tested.

Of all the Edcon brands, Edgars, in its department store format, has “the steepest road to climb”, says Govender, because of the sheer number of high-quality competitors.

The new entrants have increased competition significantly and, in the face of this, local brands have had to revitalise their operations to stand out and compete, as seen with the likes of Mr Price and Foschini, he says.

“I don’t believe that Edgars has what it takes in its current form to compete from a fashion perspective, and it is a slippery slope to try and compete from a price perspective, so serious challenges remain ahead,” he says.