Family album: Mashadi Kekana with her father Lesiba Kekana. She felt that after his death much of the responsibility of keeping the family together fell on to her shoulders.

“We cannot forget anything. Memories may escape the action of will, may sleep a long time, but when stirred by the right influence, though that influence be light as a shadow, they flash into full stature and life with everything in place.” — From A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf by John Muir, who laid the foundation for conservation in the United States

The heater bar that works glows a bright amber as it hums softly, slowly warming up the room and providing a sharp contrast to the chill outside. On the TV, the newsreader narrates a story in isiXhosa in a monotone and, although no one in the room can understand what she’s saying, eyes are glued to the screen.

Papa leans forward in his blue reclining armchair with the peeling leather — a set of two he bought at a yard sale in Irene, Pretoria — and reaches for his chipped green mug of steaming tea. Mama, in the matching armchair, cradles her cup in her hands as she slowly shakes her head at the TV screen. Then there’s me, lying down on the chocolate two-seater couch, wondering for the hundredth time why we have to watch the news in isiXhosa at 7:30pm and again in Sepedi at 8:30pm.

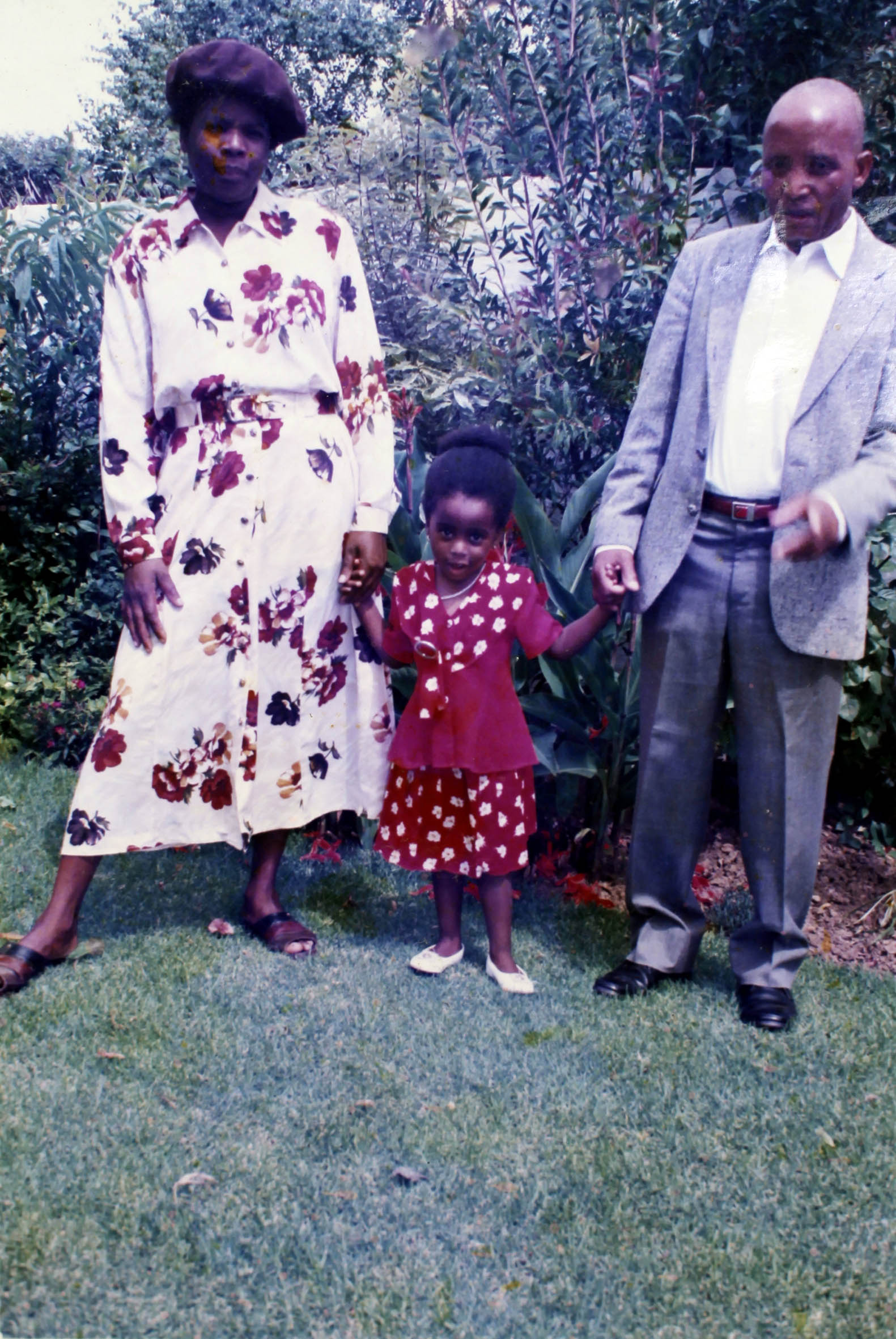

Family album: Mashadi Kekana as a toddler with her parents. Photo: Supplied

This is one of the clearest memories that comes to mind whenever I think of my father because sitting together in the living room every evening and watching the news with a cup of tea before bedtime was a ritual that was important to him.

I hadn’t thought about our living room bonding sessions for years until I found myself spring cleaning the house room by room over the December holidays.

I methodically went through the bedrooms, bathroom and dining room before finding myself at the entrance to the living room — broom, feather duster, bucket and mop in hand. I started the laborious task of moving the couches, the two armchairs and the coffee table and carefully removing the “special guests” glasses and tea sets from the room divider while humming a gospel tune to keep me going.

My mother was helping me to move the heavy carpet out of the room when she bumped into the armrest of a chair and casually said: “Re se ke ra senya setulo sa Papa [We mustn’t damage Dad’s chair].” It sounded like an innocent and passing statement except, when she called it my father’s chair, it occurred to me that the last person I saw sitting in it was him, 10 years ago.

It also hit me that the last time my family just sat in the living room and bonded, or even just watched TV, was also when he was still alive.

When my father died in 2008, I was two months shy of turning 15 and was so angry that he’d be so selfish as to just die after what I thought was a short illness. Yes, he was very sick at the end and I could hardly recognise him, but it just felt so sudden and uncalled for. I eventually understood, with the aid of hindsight, that my father had been sick for years and that he had gradually deteriorated in front of my eyes. I couldn’t see it then because he kept up a facade of strength and health for my sake.

It was September when my father died and he had asked to spend his last days at my grandmother’s house, his childhood home, which is where he departed. The family decided to hold the funeral at my grandmother’s home, which meant that no family members and friends descended on our home to drink their tea and scones in the living room while funeral preparations were under way.

Soon after the funeral, my mom, three older brothers and I retreated into our own rooms, alone with our thoughts and pain. Over time, my mom moved the TV from the living room to my bedroom down the passage. My bedroom gradually became the new living room where everyone came to spend their evenings chatting and watching TV and this is how it’s been for years.

It comes as no surprise to me that my bedroom is the new gathering place for my mother and siblings because my mom has relied on me heavily since my father died. I knew from the day we buried him that I, the only daughter and the last-born, was now responsible for bringing the family together.

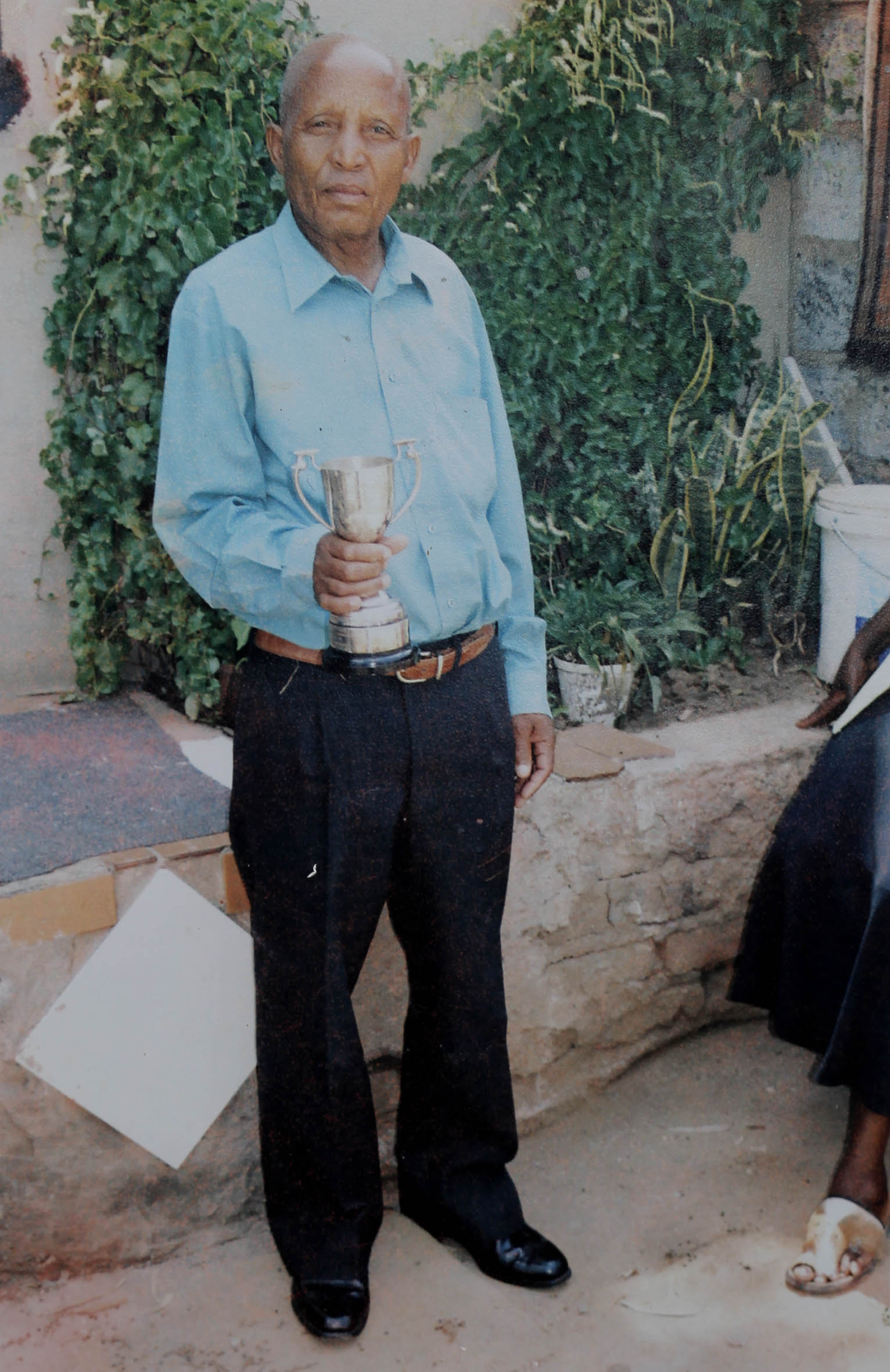

Mashadi Kekana’s father proudly holds his daughter’s academic achievement award. His death evoked emotions that the teenage Mashadi found difficult to process, though he had been sick for some time. Photo: Supplied

I will also be the first to admit that it is a huge weight on my shoulders, especially because life will never be the same as when Dad was alive.

The last memories I have of using the living room were when my Dad was still a picture of health and he was gently urging me to pay attention to the news and take an interest in what’s happening outside of my small world, “because education and knowledge is the only thing people can’t take away from you, Small”, he’d always say.

“In endowing us with memory, nature has revealed to us a truth utterly unimaginable to the unreflective creation, the truth of immortality.” — From The Life of Reason by Spanish-American philosopher and poet George Santayana

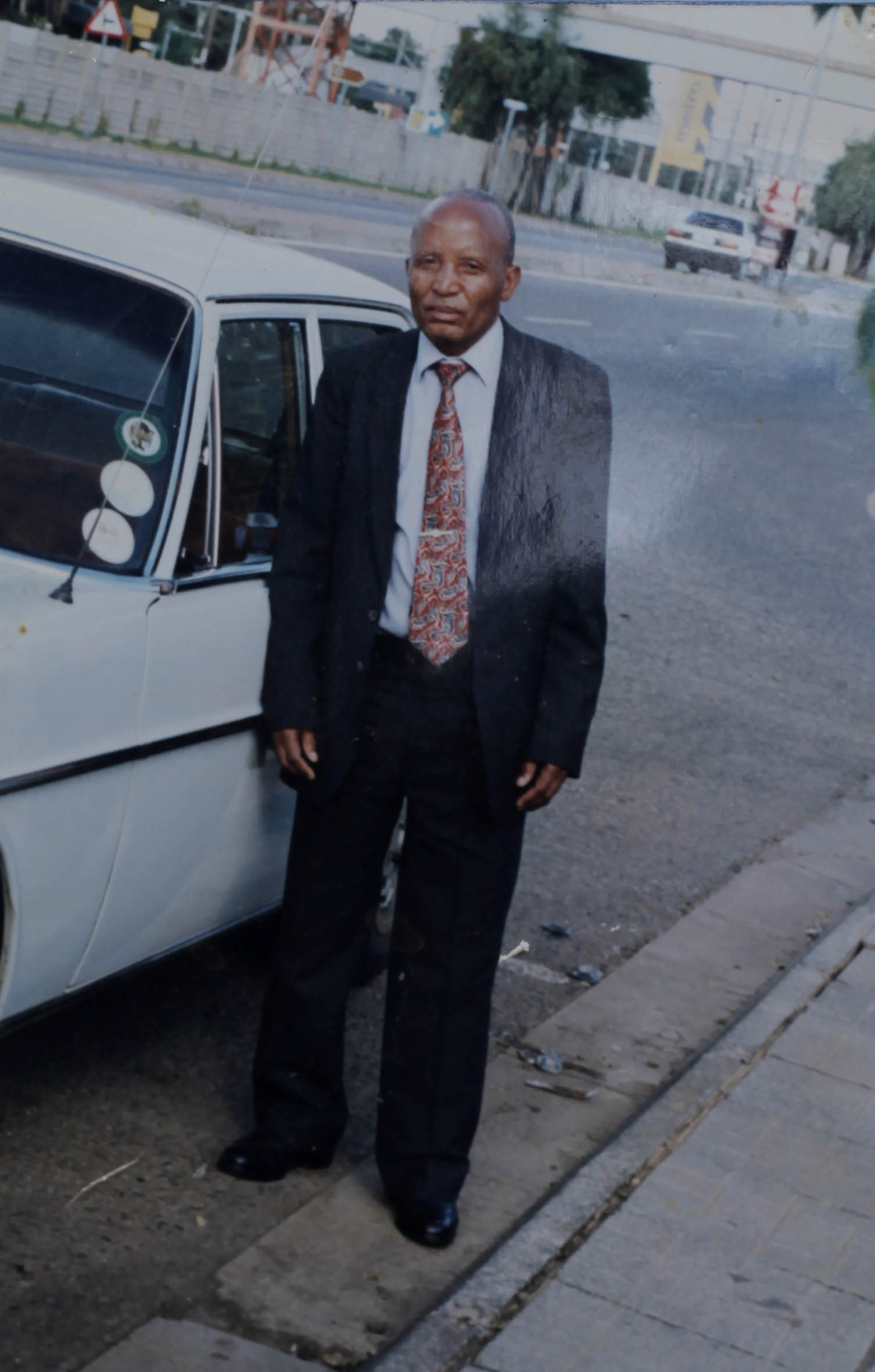

Because our family home is in Limpopo and I now live in Johannesburg, without even realising it, I have been able to avoid interacting with the living room when I visit. The same applies to my mother and siblings. The living room is situated in a place that does not require us to go into it for anything except to clean it. The only change we’ve made to it in 10 years is to hang an enlarged photo of my father in a smart suit and standing next to his beloved 1977 white Mercedes-Benz E-Class. We put up the photo soon after the funeral.

Mashadi Kekana’s father stands next to his beloved 1977 white Mercedes-Benz E-Class. Photo: Supplied

In Sepedi we say that motho o tsamaya le sa gage — a person leaves with what is theirs, what they care for. When my father died, he “left” with so much happiness, love and laughter. But the biggest gap he left us with is how he always brought us together in the living room.

The thing I’ve learnt about memories is that they are sometimes erased from the mind as a way to help us to cope with a traumatic or painful experience and to focus on other, more positive things. But these memories are never gone forever and there comes a time when you are forced to deal with them.

The funny thing about my memory is that I can remember so many details of a specific day in the living room. My father was wearing his favourite grey woollen cardigan with a white trimming. He was working on a newspaper crossword and would occasionally lean forward in his chair to ask me to help him with an answer because he believed I knew everything.

But I sometimes can’t remember the sound of his voice or some of the foods he liked. I blocked out so many memories of my father because the loss was overwhelming. Now my struggle is about whether it is time to face the memories. In all honesty, it’s a challenge to envisage the family putting our living room ritual back into motion because it will never be the same without Papa. But perhaps it’s time my family has an honest conversation about how we stay united in a way that honours Dad’s memory. I am sure that he would want us to continue using the living room to connect with each other.

The strange thing about memory is there are experiences it retains and then there are those it lets slip through the cracks. Some memories rush into the mind all at once and demand attention while some knock tentatively on consciousness’s door, hoping they’ll be given an opportunity to be let in.

It’s complex, this memory thing.