Marginalised: Carol Moses, who led an anti-apartheid march at the age of 14, was one of the independent youth leaders of the 1980s overlooked by the ANC leadership when it came to power. Photo: Student Voice/UWC Archive

TRIBUTE

Carol Moses, who died at the age of 50 recently after a short illness, symbolised the marginalisation in the post-apartheid ANC and South Africa of some of the great talent of the movement in the 1980s.

As a 14-year-old, Moses led the 1983 United Democratic Front (UDF) march in verkrampte Oudtshoorn and, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was one of the country’s most dynamic, astute and forward-looking youth and student leaders.

The marginalisation of a large cadre of capable, committed and honest leaders, and particularly the politically active youth generation who ushered in the new democratic era, is certainly one of the reasons for the ANC’s moral backslide, implementation failures and spiralling corruption.

In the scramble for positions when the ANC was unbanned in 1990, much of the ANC in exile took control of the movement, leaving some of the most capable leaders from the internal wing on the sidelines.

Moses was involved in the youth activist movement during that period. The first was as a high school student in the early to mid-1980s, when a new generation of black youth-led politics exploded. It followed a lull in the aftermath of the 1976 youth uprisings, when activists were jailed, banished or fled into exile.

The youths of the 1980s are not as celebrated as those of 1976 but, in terms of the loss of innocence and education, and the inculcation of a new culture of violence, they may have paid a higher price.

On May 28 1980, high schools for black pupils embarked on a boycott in protest against inferior education.

Many schools were closed and pupils launched the “each one, teach one” campaign, in which they taught one another and made schools “liberated zones”, where the police and white apartheid inspectors were not welcome.

Moses was active in the Congress of South African Students, which, in 1982, adopted its seminal student-worker action programme. Pupils called for democratically elected student representative councils, and supported community and worker struggles. High school activists became involved in bread-and-butter community struggles, protesting over high rents, lack of public transport and the need for better wages for black workers.

In 1983, high school activists actively helped to form regional structures for the newly launched UDF and to infuse a culture of questioning, democratic decision-making and consensus-seeking among large numbers of youths.

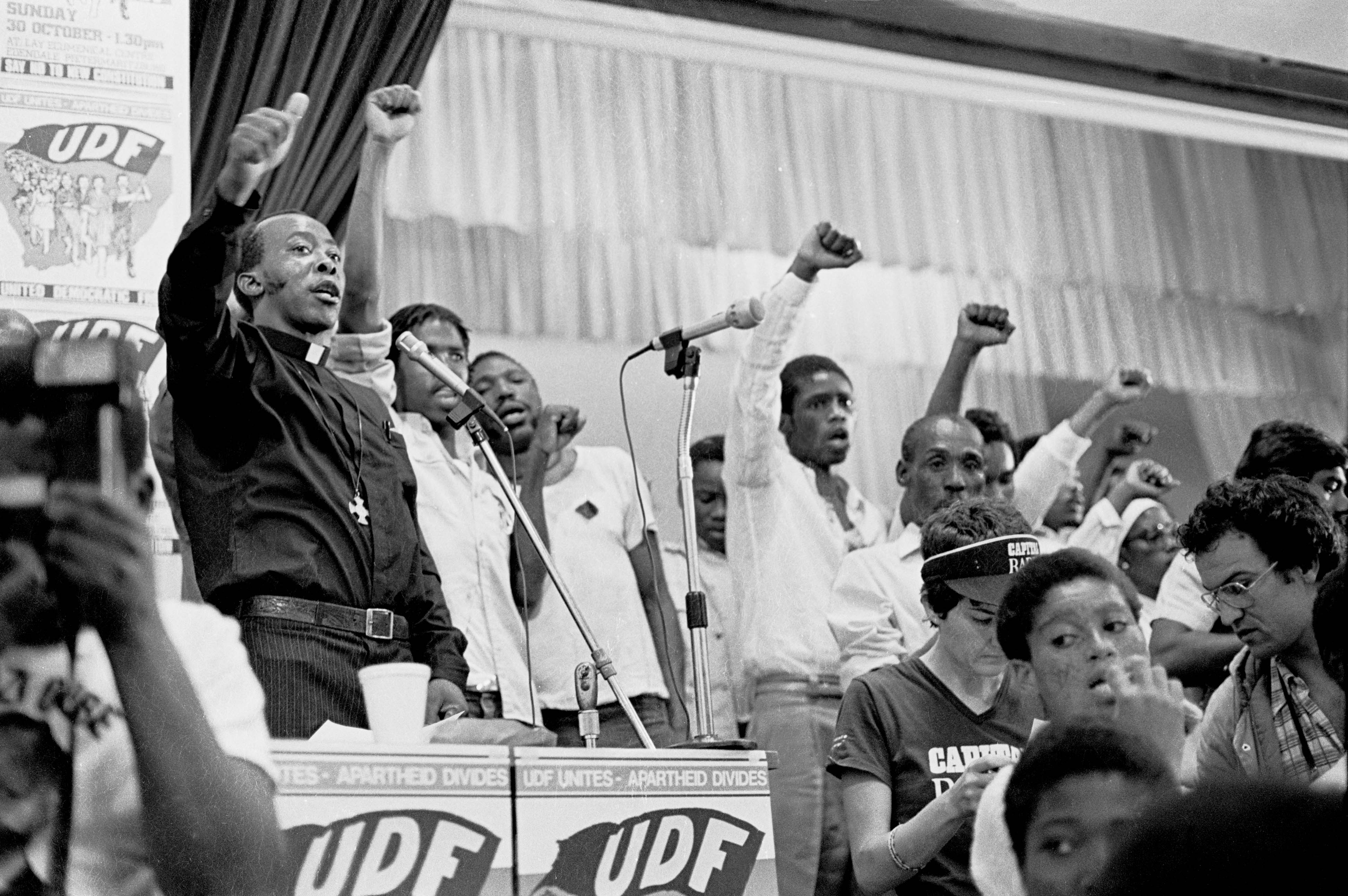

The first UDF public meeting in Pietermaritzburg, Oct 1983. Photo: Billie Paddock/ Robben Island Mayibuye

As a high school activist at the Morester Secondary School in Oudtshoorn, Moses led pupils to boycott “gutter” education. She was detained in 1983 for organising an illegal march and public violence after hitting back at the police and placed in solitary confinement and tortured. But she remained defiant.

That kind of trauma scars a person for life, often affecting their health, intimate relationships and politics. It is extraordinary that, throughout her life, Moses remained caring and warm, and laughed easily.

While at high school, Moses contributed to Saamstaan, one of the great rural community newspapers of the 1980s, during a time when these anti-apartheid newspapers were flourishing around the country, despite being banned regularly, sabotaged and attacked violently by the apartheid security forces.

After the demise of official apartheid, most of these newspapers, which often were at the centre of community life, closed down when foreign donors withdrew funding and the new democratic government did not advertise in them.

The ANC government often did not see the important need to provide state funding to community newspapers so that they could continue to provide information, build social cohesion and hold local elected and public representatives accountable.

When, in the late 1980s, Moses enrolled at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), she was almost immediately elected on to the students’ representative council. In the 1980s, UWC was known as the “peoples’ university” and the “home of the left”, and had become the site of the most prominent intellectual capital of the South African left of all hues.

When the ANC was unbanned in 1990, some of the intellectual luminaries of the ANC, returning from exile or political imprisonment, and many progressive intellectuals from formerly white South African universities joined the university. There the beginnings of South Africa’s Constitution were written, the outline of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was cobbled together and some of the key positions of the ANC during the negotiations for a democratic South Africa with the National Party were thrashed out.

Moses took up the cudgels for students who were being excluded because of a lack of money and lobbied for a national student aid scheme and for gender equality.

Many activists fighting for the liberation of South Africa were themselves steeped in patriarchy, sexism and homophobia. Women leaders like Moses had to fight a triple battle — one against apartheid oppression, another against prejudice against women in the liberation movements and yet another in society.

Although she fought many intractable battles, fighting tribalism, patriarchy and sexism among her own supposedly progressive comrades must have been among the most disheartening for her, for whatever progress we have achieved in formal democracy, their persistence makes a mockery of democracy in real life.

Moses grew up in Oudtshoorn at a time when everyone still knew each other, where moral values were strongly imbued and where social solidarity was important. She had an independent streak, often publicly holding strong contrary views when conforming would have made her more popular. She was tough on corruption and critical of incompetence and dishonesty.

The early-1990s generation of ANC-aligned student leaders were among the first to call for the unity of the anti-apartheid black and white national student movements to symbolically lead the way to reconciliation across the colour line in national politics. UWC at the time dominated black national student politics and the issue of whether the time was ripe to unite the two wings of the student movement while apartheid was still entrenched deeply divided the student body. Moses was a strong proponent of unity.

The black South African National Student Congress and the white National Union of South African Students eventually merged in 1991.

As aspects of the dominant military culture of the ANC in exile began to dominate the newly returned and amalgamated national ANC, following the party’s unbanning in 1990, the more open cultures of the internal wing started to erode and tendencies such as popularity based on shouting the most radical slogans and struggle accounting also began to creep into the student movement.

The 1980s youth activists’ culture of questioning, democratic decision-making and accountability now wilted and many homegrown activists who cut their teeth in the internal struggle were elbowed out.

At UWC, Moses was instrumental in establishing Student Voice, a student newspaper, of which she became the editor. By the early 1990s, Student Voice would become one of the most influential black student newspapers of the apartheid era.

After her editorship of Student Voice, Moses was elected national president of the South African Students’ Press Union, making her among the most influential figures in the country’s national student and youth movements during the transition from apartheid to democracy.

In the period 1983 to 1993, the ANC temporarily lost its hegemony in the domestic anti-apartheid struggle to local, mostly youth activists. The child and youth activists of the 1980s operated almost like the characters in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: they defied the apartheid state and their parents, elders and traditional authorities, whom they regarded as being too submissive to whites, and used violence to counter the violence of the apartheid state. The slogans “Victory or death” and “No education without liberation” personified this defiance.

They were the youth who formed the self-defence units to protect communities against attack by the apartheid police, the army and gangsters. They also fought against Bantustan leaders who were allied to the apartheid government. They fought not only white apartheid but also black traditional autocracy, patriarchy and corruption.

The late United States poet Mary Oliver wrote movingly that: “When death comes like the hungry bear in autumn/ when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse …/ When it’s over …/ I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world …”

Moses, did not simply visit this world — the sacrifices that she and others like her made helped bring about the collapse of apartheid.

South Africa’s great project of nonracialism, democracy-building and inclusive development will falter if we continue to marginalise not only the talents of the many Moseses out there, but also the core values she stood for: genuine democratic decision-making, nonracialism, caring for others and humility.

She is survived by her husband, Clive Stuurman, and their child, Che.

William Gumede is executive chairperson of the Democracy Works Foundation. He succeeded Carol Moses as editor of Student Voice.