Close to 100 jobs at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) are on the line as the continents leading research centre undergoes restructuring (John McCann)

Close to 100 jobs at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) are on the line as the continent’s leading research centre undergoes restructuring. Recently departed employees say this will severely affect its capacity to do crucial research, especially related to climate change.

That research has played a pivotal, behind-the-scenes role in informing policy. During COP 21, in Paris in 2015, its research helped the South African delegation to argue for stronger climate change targets.

Although the Paris Agreement says countries need to do whatever they can to keep global warming to below 2°C, it comes with a further — aspirational — goal of keeping it below 1.5°C. This is in part because the CSIR data showed that subtropical regions in Africa are warming at 1.5 times the global average. This is just one of the CSIR’s critical interventions.

In the restructuring, departments that are being dissolved and merged include natural resources and the environment; defence, peace, safety and security; research development and innovation.

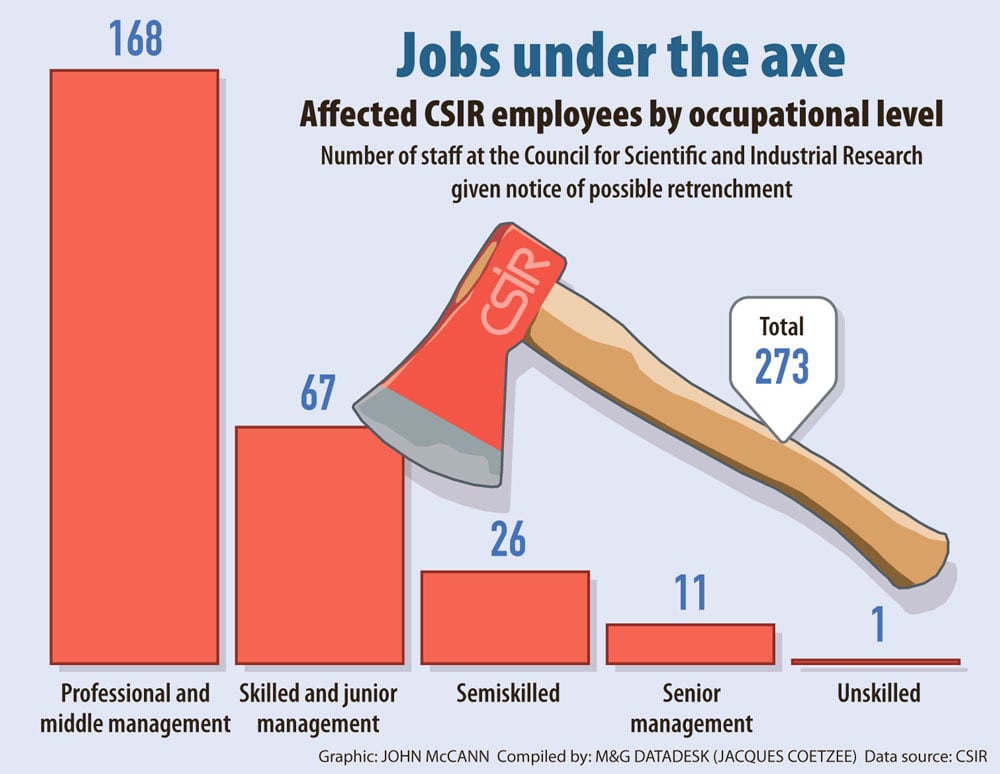

More than 270 staff members, mostly in mid-manager positions, received notices of possible retrenchments in December. At least 46 employees took voluntary severance packages and a further 127 have been moved into different positions in the organisation in a process facilitated by the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA).

Dumisani Mavundla, spokesperson for the CCMA, declined to comment on the matter.

According to Tendani Tsedu, spokesperson for the CSIR, 99 staff members have yet to be placed and are undergoing a re-interviewing process. He said restructuring was necessary because some areas of the business were no longer financially viable.

“The need for austerity measures is necessitated by the failure to raise resources to sustain a group or unit’s operations.”

He added that restructuring included restricting recruitment to critical positions only, in particular for positions directly linked to secured contract funding.

“I’m extremely sad. I’m heartbroken to see the erosion of climate and environmental research at the CSIR,” said a former employee, who preferred to stay anonymous for fear of potential reputational damage.

The internationally renowned ecology professor at the University of the Witwatersrand, Bob Scholes, who worked with the CSIR from 1992 to 2014, said that recent developments at the research institute will have ripple effects across South Africa.

“The retreat from environmental research at the CSIR is most damaging to the CSIR itself, its reputation and ability to provide integrated knowledge-based solutions to government, the private sector and society at large,” he says.

“It will cause a setback to certain types of complex, high-tech, large-scale research in the country, but if the pieces are quickly rescued and given a new home, the damage will be temporary.”

Another former employee, who took the voluntary retrenchment package and also spoke on condition of anonymity, said the loss of skills would impede the research facility’s mandate.

“They’ve lost a lot of senior people. I don’t see how the CSIR can continue to be a leader in publicly funded climate and environmental research,” said the former employee.

Tsedu said that more than 80% of the CSIR’s income comes from the South African public sector and the restructuring is aimed at decreasing its dependence on the state.

CSIR received a parliamentary grant of R1.2-billion for this financial year, this includes R359-million from the department of science and technology.

But the former employee said publicly funded research is important because it drives some of the most basic research on climate change and related policy-making. “Without publicly funded research, [the country] can’t understand some of the fundamental climate and environmental questions facing South Africa and the continent.”

Another former employee, who also requested anonymity, said the CSIR’s department of natural resources and the environment was at its peak in 2013 when it had more than 200 environmental researchers.

“At the end of March, this unit will cease to exist,” said the former employee.

“South Africa punches significantly above its weight in terms of climate and environmental science. South Africa is a strong leader in the big multilateral climate agreements … I don’t see the CSIR taking a leadership role in that any more. And I’m not sure that they want to, to be honest.”

But the CSIR said it has more than 150 environmental researchers. Tsedu denied the restructuring will negatively affect environmental research. Instead, the researchers will be moved into a new department called the “smart places hub”. He said this unit aims to assist industry with “smarter resource management, conservation and competitive manufacturing environments”.

“Our environmental researchers will increasingly focus their research in the direction of the needs prioritised as part of this effort, thereby elevating the CSIR offering and developing their careers in line with the changing business environment.”

Taslima Viljoen, the spokesperson for the department of science and technology, would only say: “I understand that you have also solicited comment from the CSIR and, as the story involves the CSIR’s restructuring, they are better placed to speak on the matter as it relates to their internal operations.”

Jacques Coetzee is an Adamela data journalist at the M&G, a position funded

by the Indigo Trust