TB remains a leading cause of death in South Africa. (Sydelle Willow Smith)

Dalene von Delft poured a glass of water and steadied herself. She could do this, she told herself, looking at the three yellow pills in her hand that she was preparing to swallow.

If I just throw them back hard enough and chase them down with some water fast enough, she thought, they’d miss her tongue completely, sparing her their gag-inducing metalic taste.

She thought it would be a small mercy, looking back over at the packets of pills that had become her life.

When the young doctor had been diagnosed with multidrugresistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) on Christmas Eve in 2010, she knew it would be hard. MDR-TB happens when the bacteria that cause TB become resistant to both of the drugs used to treat common TB and it takes about two years to treat — four times longer than normal TB.

Von Delft had to take nearly 30 tablets a day and six months of painful daily injections. Some of the regimens put her at risk of anything from psychosis to permanent deafness.

At first, Von Delft had been hopeful. After all, she’d been to medical school and was strong, with the endurance to pull the 30-hour shifts that are a hallmark of a junior doctor’s life.

To boot, her husband, Arne, was also a doctor.

“I can do this,” Von Delft told herself, looking at the container of pills on her first day of treatment. “Let’s go for it.”

Months later, the picture was less rosy.

Those dastardly little yellow pills had done a number on her thyroid, causing it to release less of the hormones her body needed to regulate basic functions such as temperature, metabolism and heart rate.

Doctors had to treat the resulting condition, hypothyroidism, with still more medication. Meanwhile, her hair had begun to fall out, her joints ached and the piles of pills left her so nauseous she threw up.

On days that she couldn’t hold the tablets down, Arne would make her take them all over again.

“It made me feel like a bully but that’s what you have to do,” he remembers. “If you don’t keep the drugs in, you don’t get better.”

He explains: “At worst, the TB becomes even more [drug] resistant.”

Von Delft looked back at the three yellow pills in her hand. Then she snatched them up, tossed them back as hard as she could towards the back of her throat, and reached for the water. There, she thought to herself. Only 20 or so more to go.

Are people with diabetes more likely to get TB? Dr Bart Willems says yes.

TB is still the leading cause of death in South Africa, according to Statistics South Africa’s most recent data from 2016. In 2017, almost 230 000 people developed active TB and of those about 16 000 were diagnosed with MDR-TB but only about half will be cured, World Health Organisation (WHO) figures show.

Globally, about one in two MDR-TB patients won’t complete the gauntlet of pills and shots, the WHO says. About one in 10 will fail treatment and double the number will either stop coming back to the clinic or will disappear from health facilities’ records altogether.

Another 15% won’t survive — particularly in Africa.

Until recently, the odds were stacked against those living with MDR-TB in South Africa. Norbert Ndjeka, head of the drug-resistant TB programme at the national health department, sketched a bleak picture:

“It was a nightmare. Patients started to gain weight and you’d get happy, so you’d do a lab test — but they would still have the disease. Then they would deteriorate again, until they died,” he explained.

During that time, the old medicines were nasty, and the treatment — as Von Delft could attest to — dragged on and was only available at specialised hospitals. About five dozen health facilities treated drug-resistant TB before 2014. With such long treatment times and limited space, this meant that patients had to wait up to three months just to get a bed, Ndjeka told delegates at South Africa’s national TB conference that year.

And unlike Von Delft, public sector patients had to endure all this often far away from friends and family.

Alone. Many couldn’t get through the gruelling 24-month course. For Ndjeka, a medical doctor, it felt like little had changed for drug-resistant patients in the more than 10 years since he’d treated the condition at public hospitals in Limpopo.

“We ran a lot of courses for doctors and came up with all sorts of material for patient education [about treatment], but there was never any decrease in the death rate,” Ndjeka remembers.

“I kept raising this and a lot of my colleagues in government and researchers at universities locally felt it was true: the drugs were probably problem number one.”

Dalene von Delft and Nokuzola Madlamba both developed MDR-TB. But diagnosed almost a decade apart, new science pioneered locally has graced Madlamba with a shorter, gentler road to getting better. (Sydelle Willow Smith)

It was the drugs — specifically the daily injections — that made Von Delft’s hearing begin to falter two months into her treatment.

“ As a clinician, especially in South Africa, we use our stethoscopes quite often. If you can’t hear, you can’t use your stethoscope and you can’t practice as a doctor,” she told the United States-based non-profit Results in 2012.

“It was a constant stress. I kept asking myself, ‘When will I completely lose my hearing?’” she said. “Then we heard about bedaquiline.”

Doctors in South Africa had been begging for the drug since 2011. The first new TB medication developed in nearly 50 years promised to replace the daily injections that had robbed so many MDR-TB patients of their hearing.

Von Delft was part of a handful of people in the country who got early access to bedaquiline, motivating with her doctor for special permission from the national drug regulator. In 2013, the government gradually began to give the medication to more people at a few health facilities where patients could be closely monitored for any problems in what it called a clinical access programme. There, MDR-TB patients and even those with the more extensively drug resistant (XDR) TB took the pill daily for two weeks and thereafter just three times a week. All the while, they also took at least three other drugs.

By six months, more than three out of four patients were no longer contagious and the fluid they coughed up from their lungs showed no signs of TB, a 2015 study in The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease revealed.

Only about half of patients with conventional MDR-TB could say the same.

By 2015, the country had rolled the drug out nationally and as of November more than 20 000 people had received the medication, according to figures collected by the international partnership DR-TB Stat, which also includes members of Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and the US nongovernmental organisation (NGO) the Treatment Advocacy Group. Today, South Africa boasts the world’s largest bedaquiline programme, according to 2018 research published in The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

Other newer drugs followed close on bedaquiline’s heels although to a lesser extent, including linezolid and delamanid, which became the focus of its own clinical access programme in 2017.

The country didn’t stop there.

It also took MDR-TB treatment out of hospitals and into clinics. In KwaZulu-Natal, not only was this more than four times cheaper than caring for patients in hospital, 2018 research published in the journal PLOS ONE found, but also a higher proportion of patients were cured of the drug-resistant bug through community and mobile clinics than when they were treated at larger facilities.

And finally in 2018, South Africa ditched deafness-inducing injections for all MDR-TB patients.

“People are excited,” Ndjeka explains. “We feel like we’re turning a corner.”

When Nokuzola Madlamba first developed a cough, she thought nothing of it. But three weeks later with the cough still there, a doctor at Michael Mapongwana clinic in Khayelitsha suggested she take a TB test.

She didn’t see the results coming: She had MDR-TB.

“I just asked, ‘Where did I get this?’ Nobody at home had TB at that time,” says Madlamba. But the former domestic worker had spent 15 years travelling between Khayelitsha and her job in Tokai on crowded buses and taxis.

“My daughter said, ‘Mommy, maybe you got it from the taxis or the bus, if somebody sitting next to you had TB.’”

The 21 pills Madlamba had to swallow each morning left her dizzy and tired. Often, she vomited them up. Constantly nauseous, she stopped eating. Her weight plummeted.

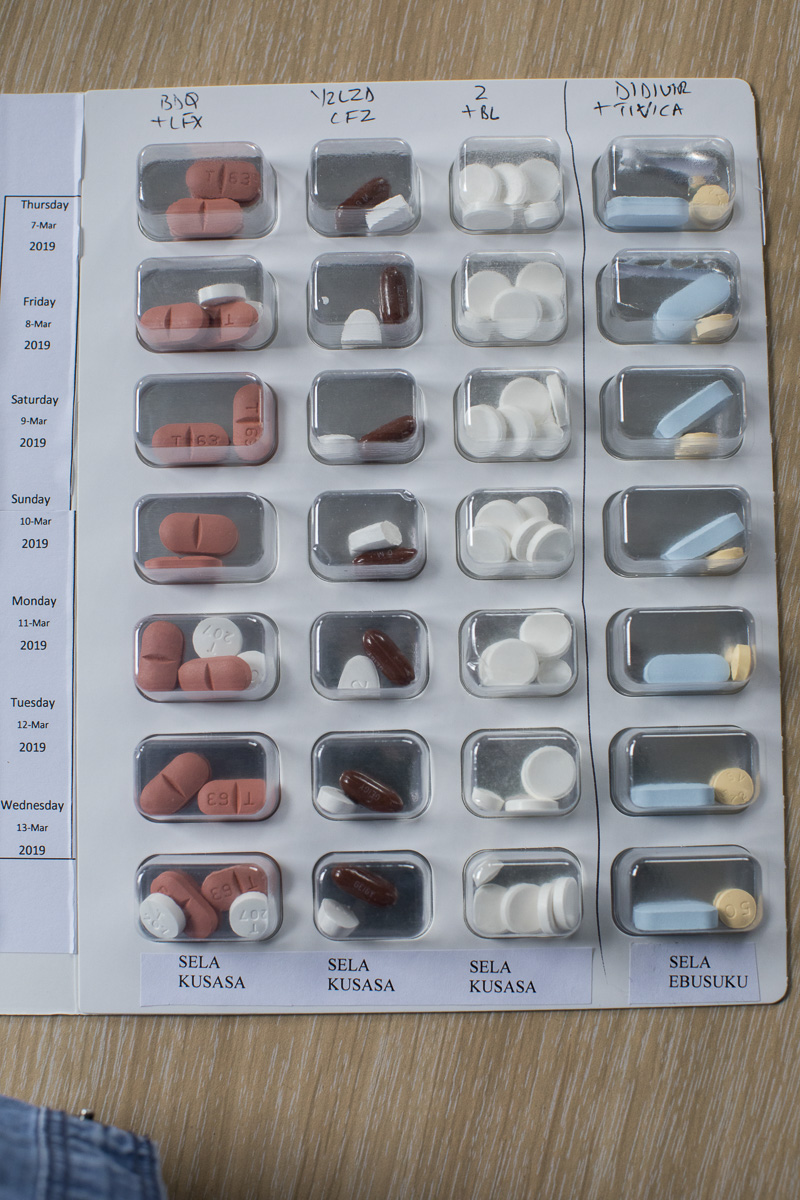

Pills, pills, pills: In the future, MDR-TB treatment could be comprised of just four drugs over six or nine months. (Sydelle Willow Smith)

“I was thinking, ‘I’m going to stop these tablets,’” she remembers. “It was too much.”

By 2016, it had become clear to the world: expecting people to be on toxic treatment for years just wasn’t working. After multiple studies showed shorter treatment could work, the WHO first recommended a nine- to 12-month course for MDR-TB in 2016. The catch? Even today, the organisation recommends a shorter drug course that still includes the daily injection that threatened to rob Von Delft of her hearing. Finding a way to change this may just depend on the newer TB drugs South Africa has been roadtesting for years.

By the time Madlamba crossed paths with researcher Jared Borain she had been on standard MDR-TB treatment for a month and was not only ready to give up, but she also weighed just 45kg, almost less than half what she normally did.

She says: “People looked at me like maybe I was going to die next week.”

Borain is a clinical manager for the End TB trial in Khayelitsha. A partnership between MSF and the international NGO Partners in Health, the six-country study is testing five different nine-month courses to treat MDR-TB and eliminate the need for those risky shots. Most regimens will feature linezolid and all will include either bedaquiline, delamanid or both.

“Even nine months is still a long time,” Borain admits.

“The problem with MDR-TB is that the medicine works,” says Borain, explaining that with treatment people start to feel like their TB symptoms are fading long before they’re cured.

“But the drugs you’re taking to combat the TB make you feel worse in other ways — for the person on the street, what the hell is the point of taking a drug that makes you feel worse?” he asks.

“So one of the things this trial tries to do is minimise side effects. ” The EndTB trial is just a piece of the puzzle into making shorter, gentler MDR-TB treatment a reality. At least three other studies into MDR-TB short courses are also ongoing in South Africa and will evaluate how well patients do on three or four drug injection-free combinations over six to eight months.

Results from some of these studies are due to be released later this year or — in the case of Borain’s trial — in 2022.

Early results from these trials have been promising. For instance, in the Nix-TB study, high-risk patients who had failed or could not complete MDR-TB treatment were given a three-drug combination that amounted to just 27 tablets a week — or about the number of pills these patients would normally be required to take daily under conventional treatment, lead researcher Francesca Conradie told Bhekisisa.

The study found that the vast majority of patients were no longer infectious after four months of treatment and were TB-free after just six months, according to findings presented at the 2017 international Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

But trials haven’t been without their problems. One of the three drugs included in the EndTB regimen, linezolid, left many patients with temporary nerve damage that led to a burning sensation in their feet and that, if untreated, could leave them struggling to walk.

Linezolid is also included as part of the WHO’s longer, recommended treatment course for MDR-TB. Finding the sweet spot between the correct dosage for patients while limiting the side effects is the next step in research, says Caryn Upton, who works at Cape Town’s Task Applied Science clinical research centre on the trial.

She explains: “Fortunately for most of our patients, it’s been almost completely reversible, but it takes months or years for that reversal to happen.”

Even though drugs such as bedaquiline, first discovered in 2004, are relatively new, the bacteria they were designed to fight is getting wise to them. Around the world, researchers are already picking up resistance to bedaquiline in some patients.

It’s not unexpected, says Task founder Andreas Diacon.

When bacteria like TB are exposed to antibiotics they can mutate, developing ways to “outsmart” medication. If even one bacterium becomes resistant to antibiotics, the US Centres for Disease Control explain, it multiplies. Over time and as people take the antibiotic, susceptible bacteria will die but the resistant ones will grow and multiply. This is how repeated use of antibiotics can increase the number of drugresistant bacteria, the organisation explains.

“The only reason for a bacterium to mutate is the presence of antibiotics, so the more antibiotics you add into the system, the more this will happen,” Diacon says. “We must keep developing new drugs; we mustn’t be happy now that we have a few ones that work.”

For now, Ndjeka says South Africa is likely to leave its new, longer bedaquiline regimen for MDR-TB unchanged.

“The major issue so far has been to reach more physicians and to train them up — that’s what we’ve embarked upon,” he explains. “At this stage, we need to pause for a year or two, keep doing what we’re doing, and then we’ll see if there are conclusive results in terms of a six-month regimen.”

In Khayelitsha, Madlamba is back from death’s door. She’s enrolled in the Nix-TB study and now takes just four tablets a day. Her appetite has returned and, at almost 63kg, is on her way back to her normal weight.

“After I drink the tablets, I’m not tired — I can still do everything at home. I can even clean the windows,” she says. “I’m just so happy.”