Devastation: More than 300 people were killed and 300 wounded in a truck bombing in Mogadishu in October 2017. No one claimed responsibility, but al-Shabab was blamed. (Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP)

NEWS ANALYSIS

In June 2018, the United States department of defence confidently told the US Congress that its military operations in Somalia, including air strikes, had resulted in zero civilian casualties in 2017. But it was lying.

A new report by Amnesty International, released on Wednesday, describes a huge increase in the US military’s bombing campaign in Somalia since Donald Trump became president, with more than 100 air strikes by drones and manned aircraft since early 2017.

According to Amnesty’s investigation of just five of these incidents, at least 14 civilians were killed, including five children. The full death toll is likely to be much higher, Amnesty concluded.

“The civilian death toll we have uncovered in just a handful of strikes suggests the shroud of secrecy surrounding the US role in Somalia’s war is actually a smokescreen for impunity,” said Brian Castner, an Amnesty International researcher. “Our findings directly contradict the US military’s mantra of zero civilian casualties in Somalia. That claim seems all the more fanciful when you consider the US has tripled its air strikes across the country since 2016, outstripping their strikes in Libya and Yemen combined.”

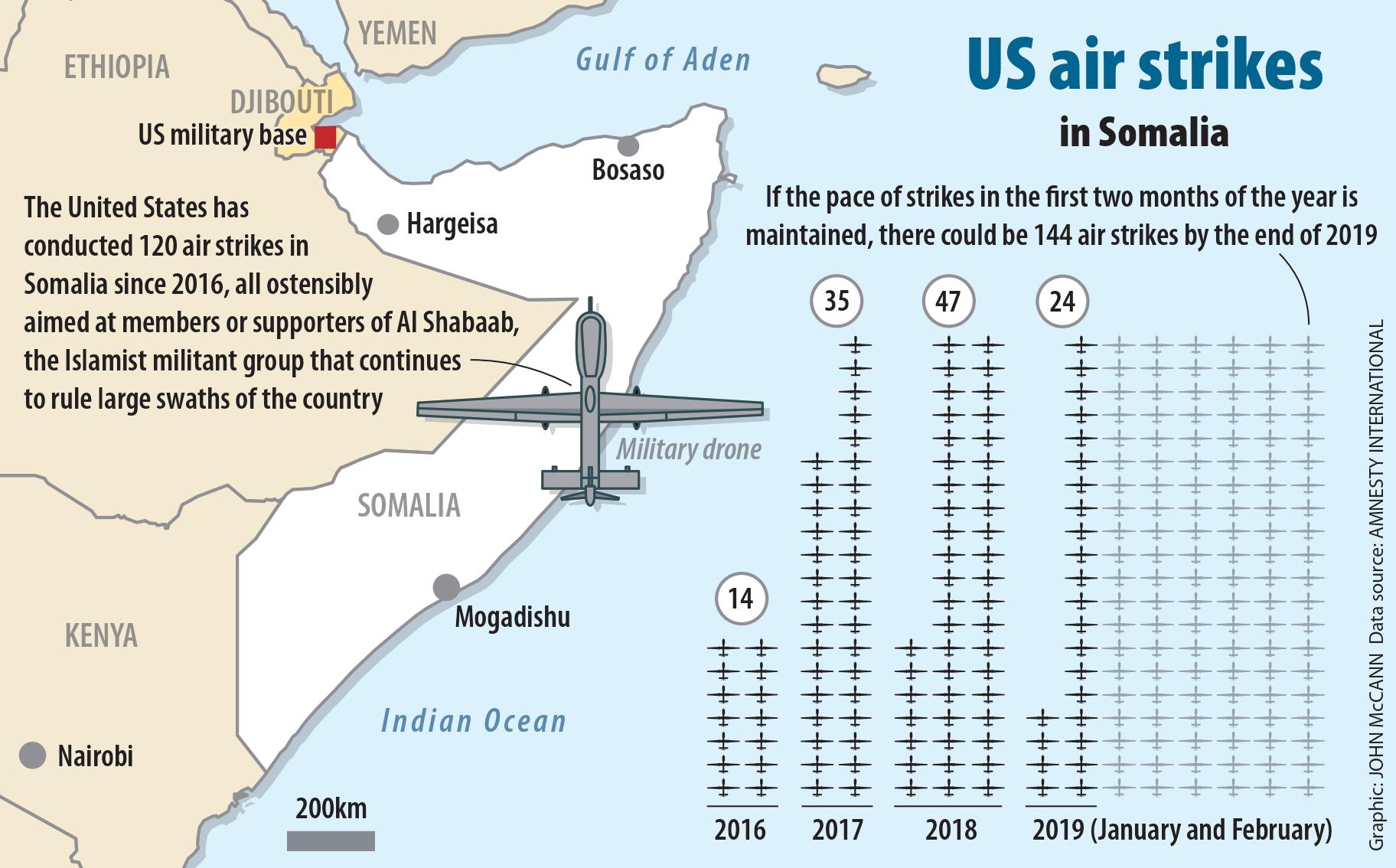

The US conducted 14 air strikes in Somalia in 2016, all ostensibly aimed at members or supporters of al-Shabab, the Islamist group that continues to rule large swaths of the country. That rose to at least 35 in 2017, and at least 47 in 2018, according to Amnesty.

In a response to Amnesty, the US Africa Command (Africom) said Amnesty’s findings “do not appear likely based on contradictory intelligence that cannot be disclosed because of operational security limitations”.

Males targeted

The sudden and dramatic increase in US military involvement in Somalia came in direct response to one of Trump’s earliest presidential directives. The full text of the directive has not been made public; all we know for sure is that it designated Somalia as an “area of active hostilities”, and significantly relaxed the US military’s rules of engagement there.

These have become so loose that almost all military-age men in al-Shabab-controlled areas are now considered legitimate targets, said a retired brigadier general interviewed by Amnesty. Donald Bolduc was the deputy director and then commander of Africom from 2013 to 2017.

Africom has disputed Bolduc’s allegation but refused to say how targeting standards are applied, citing security reasons.

“If General Bolduc is accurate in how the policy is practically applied, then such an approach to targeting would be contrary to international humanitarian law,” said Amnesty.

After Black Hawk

The US has a long and ignominious history of intervening in Somalia. Everyone remembers the film Black Hawk Down — the downing of the American helicopter in 1993 that showed images of American corpses being dragged through the streets of the capital, Mogadishu.

The incident left such a scar on the superpower’s psyche that it fundamentally altered the US’s risk threshold, contributing to Washington’s decision not to get involved in helping to avert the Rwanda genocide a year later.

Soldiers examine the blast mark of a car bomb near Sanguuni military base, in which an American special operations soldier was killed in 2018. (Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP)

Soldiers examine the blast mark of a car bomb near Sanguuni military base, in which an American special operations soldier was killed in 2018. (Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP)

For Somalia, another US intervention would have far more wide-reaching consequences. In 2006, the country was mostly under the control of the Islamic Courts Union, a conservative Islamist group who was far too Islamist for the administration of George W Bush, then in the early stages of what would become the “global war on terror”.

The US supported an Ethiopian invasion to get rid of the Islamic Courts. It worked, at least in the short term; the Islamist group was removed from power and mostly destroyed. But hardline elements in the group, embittered and ultimately emboldened by the invasion, went on to form a far more radical and far more dangerous organisation known as al-Shabab.

The US’s war against al-Shabab began almost immediately, with three air strikes in 2007 that killed 21 people. It has continued ever since, in the form of bombing raids, drone attacks and even the very occasional ground operation.

Nothing seems to have worked, however. Although its fortunes have waxed and waned, al-Shabab remains a potent force. Three weeks ago, on March 1, al-Shabab fighters seized several buildings in central Mogadishu. Security forces took a full day to clear the buildings, and 24 people, mostly civilians, had died by the time order had been restored.

Time and again, both the Somalia National Army and the relatively well-resourced African Union Mission in Somalia have proved powerless to prevent such attacks. Nor have US air strikes made much of a difference, as the US itself clearly understands.

“At the end of the day, these strikes are not going to defeat al-Shabab,” admitted General Thomas Waldhauser, the head of Africom, at an appearance before the US Congress last month. This has not stopped him from ordering more air strikes on Somalia than anyone else in history.

What war?

In yet another congressional briefing, in March 2018, Waldhauser let something slip. “I wouldn’t characterise that we’re at war [in Somalia]. It’s specifically designed for us not to own that,” he said.

That “specific design” relies on air strikes, usually from unmanned aerial vehicles. Using drones allows the US to bomb Somalia at arm’s length, without ever having to admit that it is “at war” in the Horn of Africa.

But for the Somalis on the receiving end of the American ordnance, it certainly feels like war.

“We have been waiting for someone to come ask us about this,” said Liban, a resident of Darussalam village, which was bombed in November 2017.

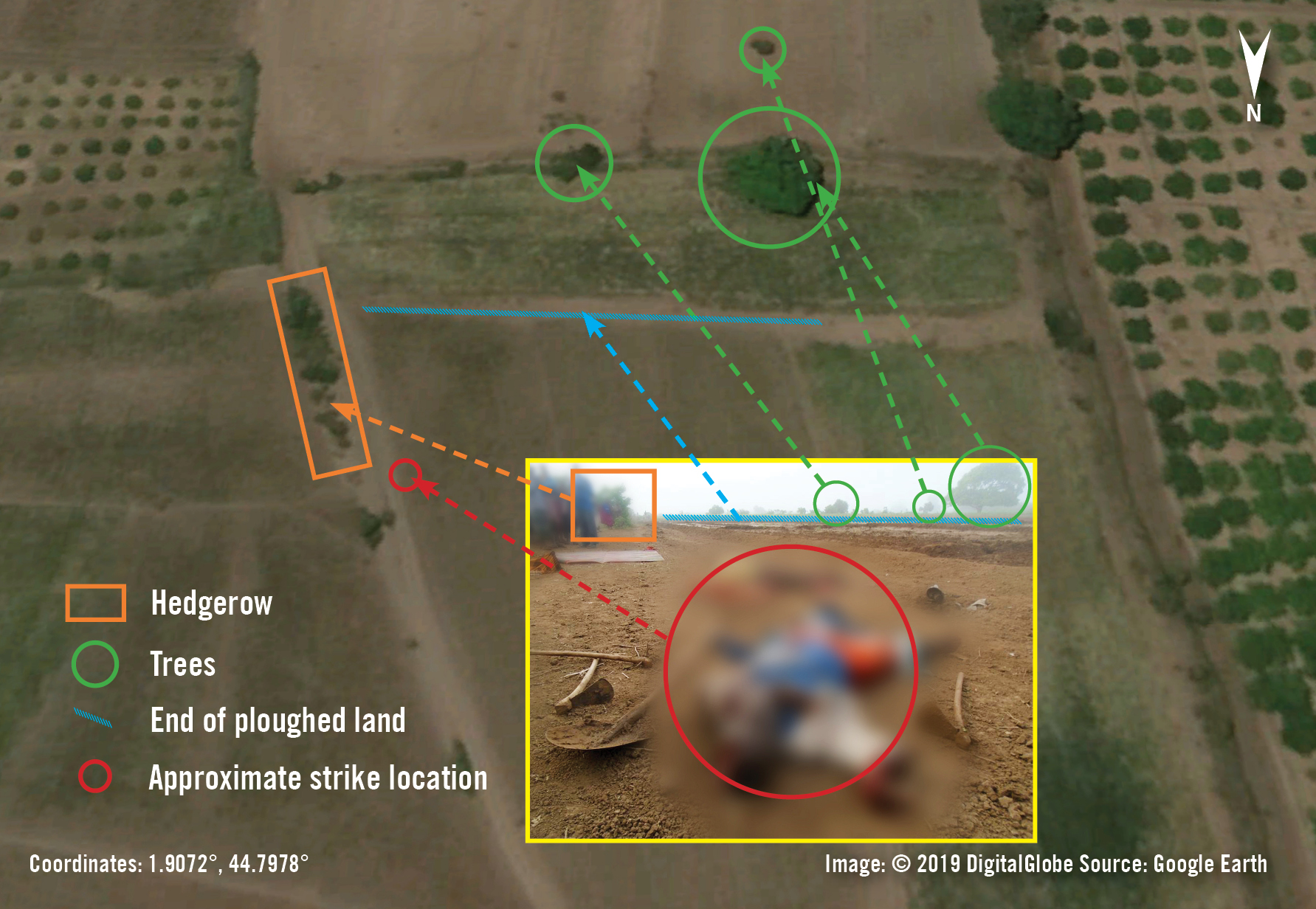

Amnesty International’s investigation concluded that three farmers, all civilians, were killed in the attackwhile they were camping under a tree, probably watching a Bollywood movie on a mobile phone that had to be kept hidden from al-Shabab. Their findings were based on in-person interviews with 18 residents of the village and its vicinity, including six eyewitnesses.

“I saw the heavy splashing light and then the big noise came and I fell down,” said Liban. “When the noise [of an airstrike] happened, everything ceased … I was so frightened. I couldn’t keep watch on the farm at all. I went under the shelter of the tree and hid.”

In the morning, when he went to check on his fellow farmers, they were dead.

Africom disputes this. “Africom conducted a precision-guided strike that corresponds to the time and location alleged, targeting al-Shabab fighters,” it told Amnesty. Its own assessment of the attack “determined that the three men described in the allegation were not sleeping at the time of the strike and were members of al-Shabab”.

Africom also disputes that it is at war in Somalia. But the routine use of drone strikes, and the increasing civilian casualty count, tell a very different story.