Free to be: After being in the industry over twenty years, artist Tracey Rose enjoys the fact that, now she is an academic, she can say and write what she likes. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

A stillness is required to engage seriously with the work of Tracey Rose. Perhaps this has to do with the attractive, carnivalesque, risqué and no-fucks-to-give nature of her medley of installation, photography, video and performance work.

Leading up to her showcase at the 58th Venice Biennale, the Mail & Guardian arranged to have a sit- down with Rose at the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of arts, where she now teaches, to review her 23 years in art. It’s the end of the first term and her first-year students are finalising projects and okaying their plans with Rose in the drawing room on the first floor when we meet. When we are in her third-floor office, she sits, elevates her injured foot, and offers cake before the conversation unfolds.

As an artist, Rose bloomed in democracy’s teething years. She remembers how this restricted the way her work was being engaged with because the art world was mostly looking to South Africa for an apartheid retrospective.

“It did the work a disservice because there was no sort of development from the critique. But there was a point where I consciously cooned. That was me dealing with an audience, media and art consumer that’s predominantly white.

“The performance that happens as an artist within that space becomes a political decision to keep the work alive, relevant and moving. If I didn’t I would be ostracised even more,” Rose admits before adding that her work went beyond addressing apartheid.

“It was more interested in how to transcend the body” — an interest that Rose drew from the Catholic doctrine, which sees the being as mind, body and spirit.

She often places herself at the centre of her own art, as in False Flag: A Deed in 2 Acts. Photo: Art Basel

The need to explore transcendence with her body is evident in Rose’s ongoing use of her physical form as a visual motif, as well as in the essentiality of performance in her practice.

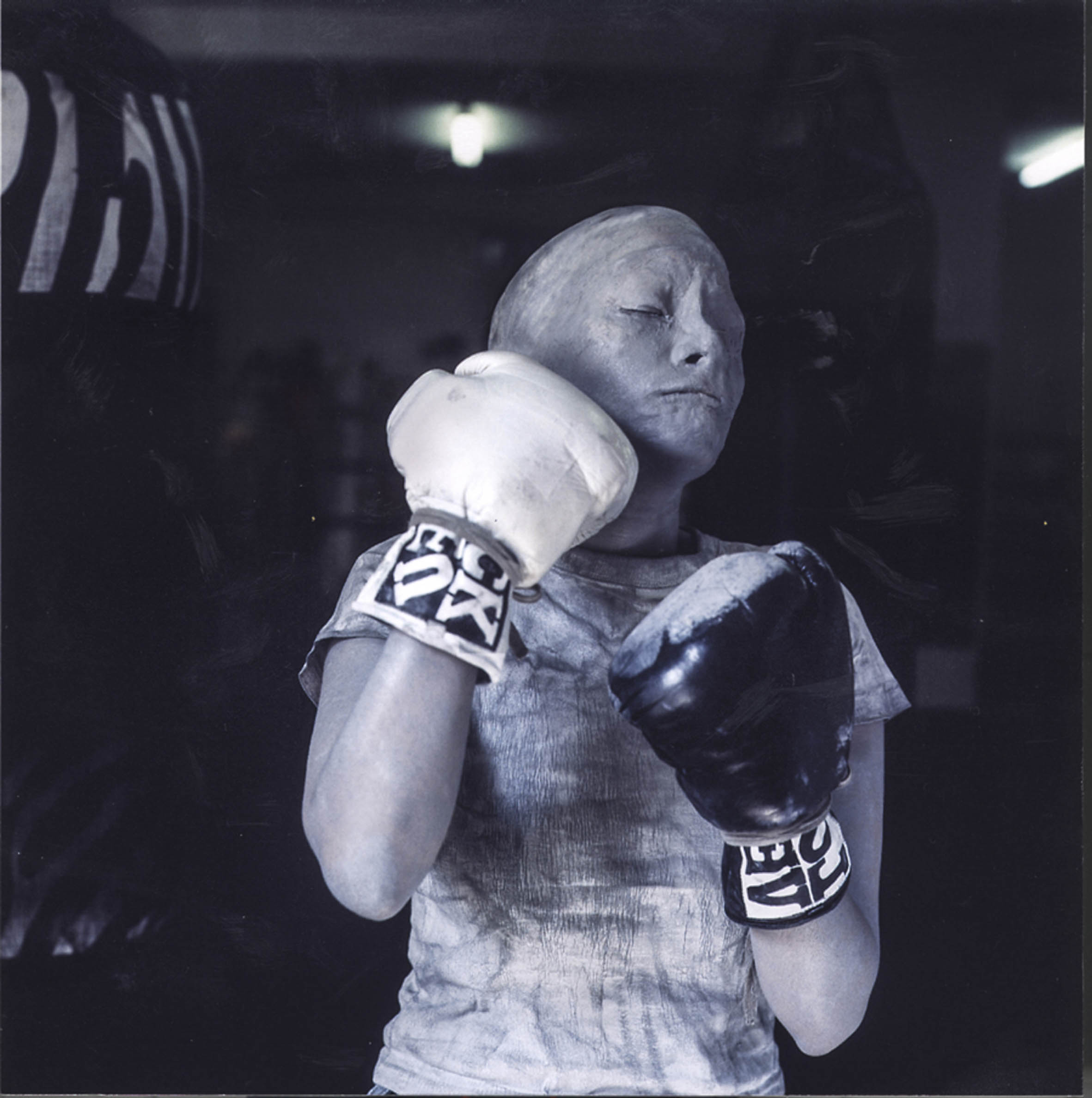

In TKO (Technical Knockout) (2001), Rose is seen relentlessly sparring with a punching bag from four different camera angles.

“That came about because I wanted to beat up a curator who wanted to do a piece on apartheid again, because there was just this glut of apartheidtures.”

One of the cameras is positioned inside the punching bag, allowing the viewer to see the punches coming at them, as if to encourage the viewer to identify with the punching bag and transcend their human form.

In preparation for TKO, Rose took up professional boxing at Nick Durandt’s gym for two years before filming.

In Ciao Bella (2001), a three-screen video installation re-enacting the Last Supper, the body is stretched beyond the expected norms by the act of Rose switching and morphing into all the installation’s characters. For Ongetitled (Untitled) (1998), she films the act of ridding her body of all its hair in an act to surpass the feminine and masculine cues of the human form. Waiting for God (2011) sees her embodying the often-quiet, tiresome and intangible act of faith by quietly waiting on the Mount of Olives in a two-hour-long video installation.

Rose goes into great detail about her performance work and the “extreme relationship that I have had with art and pushing the parameters of freedom of expression.

Pushing boundaries: Tracey Rose’s KKK Supreme (top) and Lovemefuckme (below) show her more radical side. Photos: Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

“I want to know how do I keep expanding what’s possible in the legal range with my body. It’s kind of theatre for adrenaline junkies. Once you start performance art, you keep chasing the dragon,” she bellows in laughter.

Exiled

In 2008, Rose was “kicked out” of her art home, Goodman Gallery. Shortly thereafter, her New York gallerist, Christian Haye, closed his Harlem-based gallery, the Project, in 2009.

“I was persona non grata for a while. At some point … the invitations stopped because I was just too fucken radical. I was too extreme for many curatorial palates. I’m still trying to figure out how to articulate that period sufficiently.

“So I started feeding off Jo’burg in a way that was incredible. I would club without drugs or alcohol from 9pm to 2am with just water. I was going into trances on the dance floor. I was connecting to this city on a vibrational level,” she says, with a smile.

Born in Durban, Rose moved to Johannesburg when she was seven and, as such, considers it her true home.

“Growing up in Jo’burg, I was accustomed to an amount of freedom and access. It’s amazing in how welcoming it is. It’s like the ideal art world because it allows everybody to come into it, to assimilate, to move around and expand it,” Rose explains.

“I stopped looking at art for a while, actually.”

She says she does not get this sense from the contemporary art scene because of how it welcomes “sameness” and “mediocrity” with open arms. She attributes this to the nature in which art is being engaged with by the media, scholars and buyers.

“I stopped looking at art for a while, actually. It’s no longer this holistic thing that you’re looking at. It’s a statement. It’s about poverty, it’s about the global crises, post-colonial this, that. Tick box, tick box, tick box. It’s got all these fucking issues and I’m just looking at shit. There’s no kind of material engagement.”

But Rose also acknowledges the role that art institutions play in producing homogeneous art.

“It’s much bigger than just the choices that people make. If you do not know what’s available for you to consume or engage with, you’re not going to do that.”

Most of what she recalls of her fine art training at Wits consisted of a European take on the arts. When it wasn’t the work of the Old Masters, the art theory included a white feminist take on contemporary art or the simplification of work by black artists to “township or primitive art” categories.

“It was all these derogatory spaces where we weren’t allowed to take the work seriously. It was almost as though they were intellectually underdeveloped.”

The veil that clouded her perception and aspirations as an artist was removed in 1995 during the first Johannesburg Biennale. Titled Africus, the biennale was the South African art world’s international coming-out party. Now that cultural boycotts were no longer in play, the biennale tried to restore the country’s artistic dialogue and exchange with the world.

“… people from all over the world, who are the most rigorous thinkers, were making work out of stuff in real time. That’s not necessarily paint on canvas; it’s material and matter that speaks. It blew my mind. I cried for a year. I couldn’t. I had a breakdown because I realised the depth of the deception and how far and controlled it was. Seeing people of colour make art in my lifetime blew me the fuck away,” says Rose.

“It’s important to know who came before. All those amazing people … I carry them with me in my work,” she says, after referring to her first encounter with contemporary artist Carlos Capelán from Uruguay.

Now based in Sweden, the 71-year-old Capelán is known for the atmospheric nature of his installation work on displacement and dislocation.

“I don’t get why these kids think they’re the first. There’s a lacking in historical referencing and reverencing. Their art doesn’t take any risks. It doesn’t love itself. It doesn’t love people. It’s only interested in power; not even power, it’s all vanity. And I don’t think people are looking at books enough.”

Rose sighs while running a hand through her loose hair in what looks like frustration.

Process makes practice

The layers of materiality in Rose’s work can be attributed to a number of things. The first is an arresting sensation to create the work.

“When the work comes, this idea, it’s more of a sensation and vision. This isn’t a hobby, it isn’t a job. The work eats me until it gets made. Once I get the message, it has to be done.”

Over the years, Rose has come to perceive the role of artists as that of neo-shamans, with the mandate to cause shifts that will birth a healing.

In addition to her heeding a higher call, what informs her work is a combination of personal experiences as well as her insatiable interest in information.

“Artists have got to be the interpreters and intermediaries in spaces. So they consume information, they go into these vile, volatile environments and you take all of it. They reconfigure it and put it through their being and then they create these things that cause a shift vibrationally, spirituality, intellectually and emotionally for the people that engage with it.

“I am also a glutton for information. I consume information all the time. I read. It infiltrates the work.”

Lucie’s Fur Version 1.1.1 – La Messiea (2003). Photo: Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

Once the ideal picture exists, the concept then passes through a series of negotiations, mostly financial, before reaching the form that will be showcased to the public.

“The work that I’m making happens, stylistically, because of all the financial restrictions that I have to go through in order to make it. Sometimes I hustle, I ask for favours. Sometimes I’m using a lesser kind of grade of material, but I know it’s like that because of the necessity of having the work made. That adds a richness to the work.

“Shit, lack is a component in my work. Well, it’s lack and necessity. The lack of having and the necessity to make it are what contribute to my technique.”

“there are more gentle ways to make art.”

Five years ago, Rose had a son. She has restored her ties with Goodman Gallery and created new ones with London gallerist Dan Gunn, and she has taken on the co-ordinating role at Wits’s fine art department.

“I like to think that I’m going into war whenever I make work. Well, I used to but now I’m not as aggressive.”

She laughs, before adding that “there are more gentle ways to make art. I mean, I’m still here.”

With its objective centred around healing, the often textless or unexplained territory that Rose’s work plays in may not always unfold as it should.

“You could read so many things into the work, issues like identity, belonging, feminism, queerness, but also issues of Western culture,” explains Khwezi Gule, who met Rose “around 2007, 2008”, and co-curated her mid-career retrospective Waiting for God at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2011 All of these things are tightly packed into her art works and we have to throw them apart little by little to get to the core,”.

Describing his engagement with her work, Gule says it is too layered to unpack in a short conversation. And, as she put it earlier, this can often restrict the public’s engagement with her texts.

With an awareness of this, Rose is currently working toward a PhD with the hopes of intellectually justifying her canon of work on her own terms.

“When you start to perform a particular character for the media or historians, you get locked into them. So even when you start writing, there’s no space for your words to be published. Now that I’m an academic, I can say what I like and write what I like. When I write what I like, it’s going to be fucken dangerous.”

Venice Biennale: Third time’s a charm

The 58th Venice Biennale marks Tracey Rose’s third instalment. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Curated by Nkule Mabaso and Nomsa Makhubu, the South African Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale will feature artists Dineo Bopape and Mawande Ka Zenzile alongside Tracey Rose.

This will be Rose’s third Venice Biennale after a 12-year resistance to participate. The first participation was in 2001 under the curatorial mentorship of the “godfather of curating”, Harold Szeemann. The second time, which Rose does not speak of too fondly, took place in 2007. Its curators, Simon Njami and Fernando Alvim, collaborated on the African Pavilion to exhibit Checklist: Luanda Pop. Because it drew predominantly from Angolan Sindika Dokolo’s collection of contemporary African art, Rose thought it was “problematic” to have one source represent a continental pavilion.

“I have been asked for the last two Biennales. I said no because they were a mess. I’m not gonna put my name to that. I’m not going to endorse mediocrity.”

She goes on to explain that, having worked with Mabaso and interacted with Makhubu’s work, accepting this year’s offer was easy.

Under the title The Stronger We Become, the department of arts and culture selected the curators and artists to represent the country with themes of social, political and economic resilience. This is in response to the biennale’s broader curatorial theme, May You Live in Interesting Times, set by this year’s curator Ralph Rugoff.

In an introduction published on the Venice Biennale’s website, Rugoff said he wanted to take a serious look at “art’s potential as a method for looking into things that we do not already know — things that may be off limits, under the radar, or otherwise inaccessible for various reasons”.

When Rose received the invitation “about a month ago”, she was asked to present one of her existing works.

“I said no,” she shrugs before leaning her head against the wall, contemplating how much she wants to share about the piece she will be presenting. “I don’t want to talk about it much because I’m a little insecure about how it’s going to be financially possible to pull off. But the content that I have in mind is so important that it can’t wait another two years. Also, it’s so provocative I want to do it now.” — Zaza Hlalethwa

The Venice Biennale runs from May 11 – November 24. Visit labiennale.org for more info