Philosophy of dignity: Zakes Mda draws on Mandingo religion. (Joanne Oliver)

‘I am a painter,” insists Zakes Mda. Well known for a long list of novels and plays, he says he’s really a painter — and now that he has retired from his professorship in Athens, Ohio, painting is his “day job”. The writing takes place after hours. But he’s still able to produce a stream of new fiction, the latest being The Zulus of New York (Umuzi).

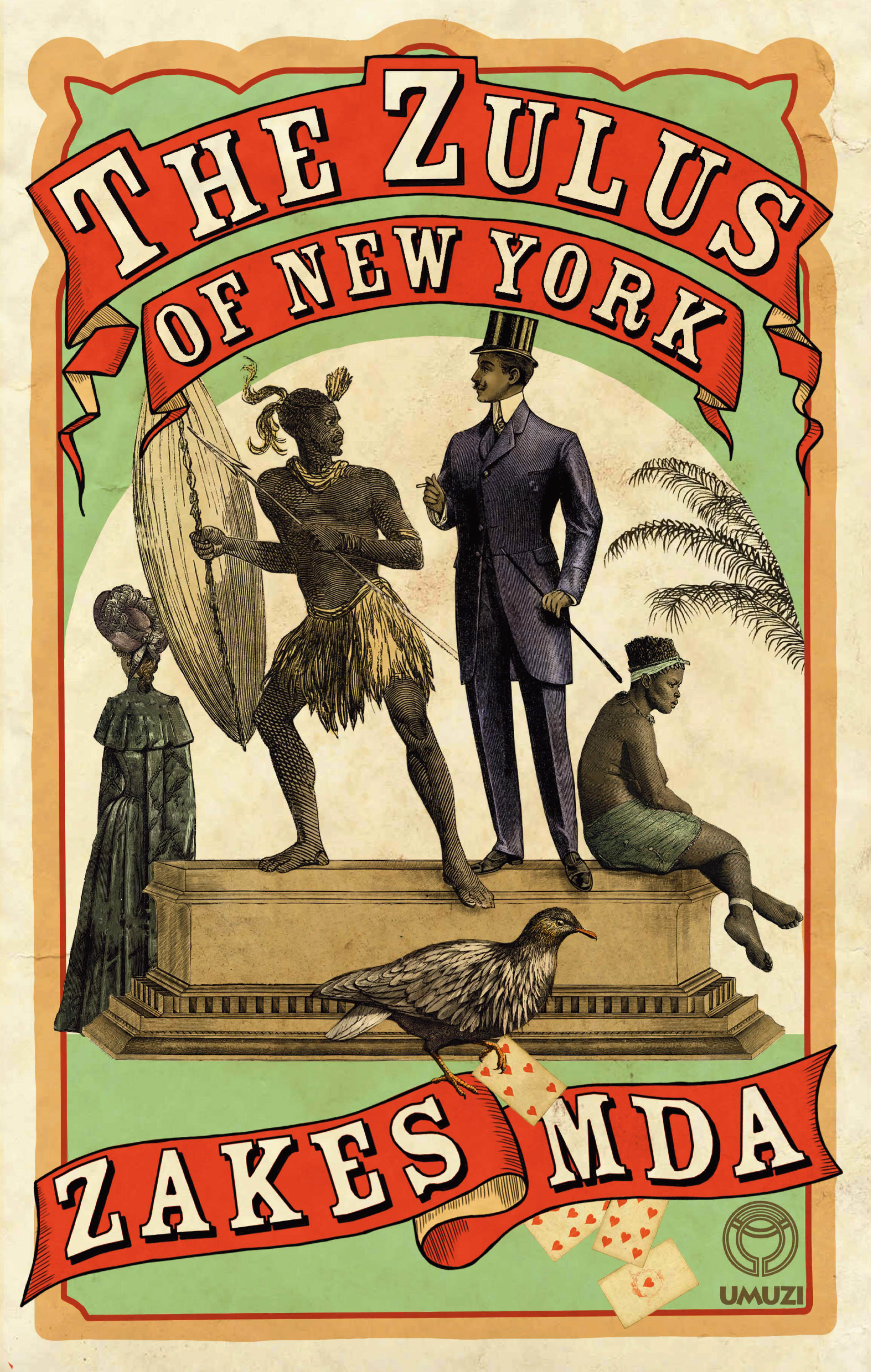

A novel from Zakes Mda’s stream of new fiction. (Umuzi Publishers)

The novel is based on historical fact. In the late 1800s, generated by limited information and news from colonies or areas being conquered by colonists, Europe and the United States developed an appetite for performing “savages” — teams who would dance, act out battles, or, in the case of one wild man depicted by Mda, gnaw raw meat for the titillation of white audiences. Many were called Zulus, though that term was really a generic one for performing black people who came from all over, even from within the US. The eater of raw meat was one such.

Mda’s protagonist is the truly Zulu Em-Pee, a corruption of Mpi (“less punishing to the inexperienced tongue than Mpiyezintombi”, as Mda writes). Em-Pee is located in this historical context by Mda who sets up the story by having him run away from the royal kraal of Cetshwayo after he commits an indiscretion with one of the king’s favoured maidens.

Em-Pee ends up on a ship from Cape Town to Britain — where he will begin his performing career — and later goes to the US, where he has a child, meets a mysterious Mandingo woman and falls in love.

“The Great Farini [the impresario] would claim these were people who actually fought at the Battle of Isandlwana, say,” says Mda. “Africans would do their dances, the same traditional dances they did at home. But Farini would insist these dances were much too orderly. The white people would not believe these savages had dances that are so well organised. Instead, they had to kick and scream and roll on the floor.

“But most of the ‘Zulus’ in New York were African-Americans,” says Mda. “Or whites, Irish people particularly, who painted their faces black! Some of them were buskers. Farini had Owambo people, and Xhosas, but he called them ‘Farini’s Genuine Zulus’.

“If you read the newspapers of the time, you see this fascination. I looked at the London Telegraph, at the Western media of the time, and for them Isandlwana was a big, big thing. They [the British] had the greatest army in the world, but they were defeated by these savages with spears. When King Cetshwayo went to London, crowds followed him everywhere. There was a great fascination.”

This fascination goes back a long way into the history of colonisation and the people colonists brought back to Europe from Africa.

“From the time of Sarah Baartman, which was nearly 200 years before the time I’m writing about, there were these displays of what were called ‘human curiosities and oddities’,” says Mda. “This included anyone who was exotic to the Western world, including Pygmies, people from West Africa. They were put in museums of natural history or, later, travelling circuses.

“That is why people like Farini would accompany these displays with lectures about who these people were, but most of it was invented. ‘This is a princess from such-and-such an island’, all of that. A whole biography would be created.”

He sees continuing parallels with the present day. “It’s still the same, even now. The West wants to see its own image of what Africa is, the image that has already been established there. A lot of African writers, today, will set their stories in urbanised Africa, but a publisher in the US will say, ‘No, I want the authentic Africa’. It has taken a different shape, but it’s the same thing.

“In New Orleans today, if you go to the Mardi Gras, they have created their own image of ‘Zuluness’,” says Mda. “When I launched this book in Stellenbosch, one lady told me a story of when they were in the Virgin Islands, and they were at a bus station when there came this huge guy wearing skins, carrying spears and so forth, who was dancing around for money. He said he was a Zulu. He was a native of the Virgin Islands, but he was performing as a ‘Zulu’. She asked him, ‘How did you know about the Zulus?’ He said, ‘I saw a movie.’ He decided this was his heritage. So it’s not just in the history I’m writing about.”

After “almost 40 years” of living in the US, Mda pays tribute to his adopted home by locating a key scene of the novel in Athens, Ohio, where one of the earliest mental hospitals in the US was founded. “It’s a museum now,” he says. “The mental facility has moved to a different site. It’s a beautiful building, very imposing. It’s haunting. People come from all over the US to celebrate Halloween there. It’s filled with ghosts.”

The novel brings together the historical reality of the 1800s as well as a mythological element that plays out in the cosmology of Acol, the Mandingo (or “Dinka”) woman to whom Em-Pee is so drawn.

“I drew from that tradition because, in history, they were among the people who were displaced and used by these impresarios in these shows. The Dinka [from West Africa] were appealing because they are very tall, pitch-black.

“I didn’t invent any of this cosmology. Their philosophy centres on dignity; it’s part of their ethos when they are growing up. Adulthood is seen as the attainment of dignity. Dignity for them has an aesthetic. It’s performative — they perform dignity. It’s a core value for them, which was important for me writing about characters who are dehumanised. But they can attain dignity by drawing on their own cosmologies, their own mythologies.”

Acol, who ends up in the Athens asylum, “puts herself back together” by drawing on her Dinka religious myths. “That was important for me,” says Mda. “She can’t be put together by someone else, by a man. There’s no knight in shining armour,” he says, although Em-Pee would himself like to play that role, in some way. She does it from her own resources.”