'New Brighton, Port Elizabeth' by George Pemba can be seen at a period-crossing exhibition at the Standard Bank Art Gallery until April 18. (George Pemba/Standard Bank Gallery)

Poised to put black modernist artists on the map, the Standard Bank Art Gallery took on the mammoth task of rescuing works from their exclusionary academic sanctuaries and brought them into the public domain in its current show A Black Aesthetic: A View of South African Artists (1970-1990), curated by art historian and head curator Dr Same Mdluli.

Comprising an eclectic number of unknown and prominent visual artists working in different styles and mediums, the show stretches across history to bring the work together into what seems to be an atavistic colloquy on modern art.

Mind you, throughout the 20th century, this dialogue was neither considered aesthetical nor modernist, but was instead classified using social Darwinist monikers such as “traditional”, “transitional”, “talismanic” or “township”, positioning African artists in a different temporal order. The power of what constituted “art” echoed the racial system that subtended it. The words “art” and “artist” presupposed an enlightened subject, individual, thinker — terms unattributable to an African.

Although today “African” appears (when it does) capacious enough that it fits across racial lines in South Africa, the perceptions of Africa, its cultures and people remain under racist circumspection: by that contradiction alone, Africa is cursed to become the world’s genie. Locating Africa outside of normalcy motivates the disavowal of its contributions (and the subsequent abuse thereof) in the modernisation of global cultures.

This raises concerns about black aesthetics being regarded as something static or confined to the “incapable” hands of black artists. This, of course, is a fallacy. Euro-American modern art is pervaded by black aesthetic forms, whether it acknowledges this or not.

The insidious shadow colonialism casts over modernism as a unidirectional cultural enterprise — the West giving to the empty-handed rest — deprives Africa not only of due recognition of its contributions in world history, but also of its claims to its own cultural productions. At times, this prejudice is hidden under the cloak of reciprocal benefit, whose raison d’être is to paint colonialism differently (à la Helen Zille). Nevertheless, African modernity isn’t in spite of, but entangled with these same adversarial displacements.

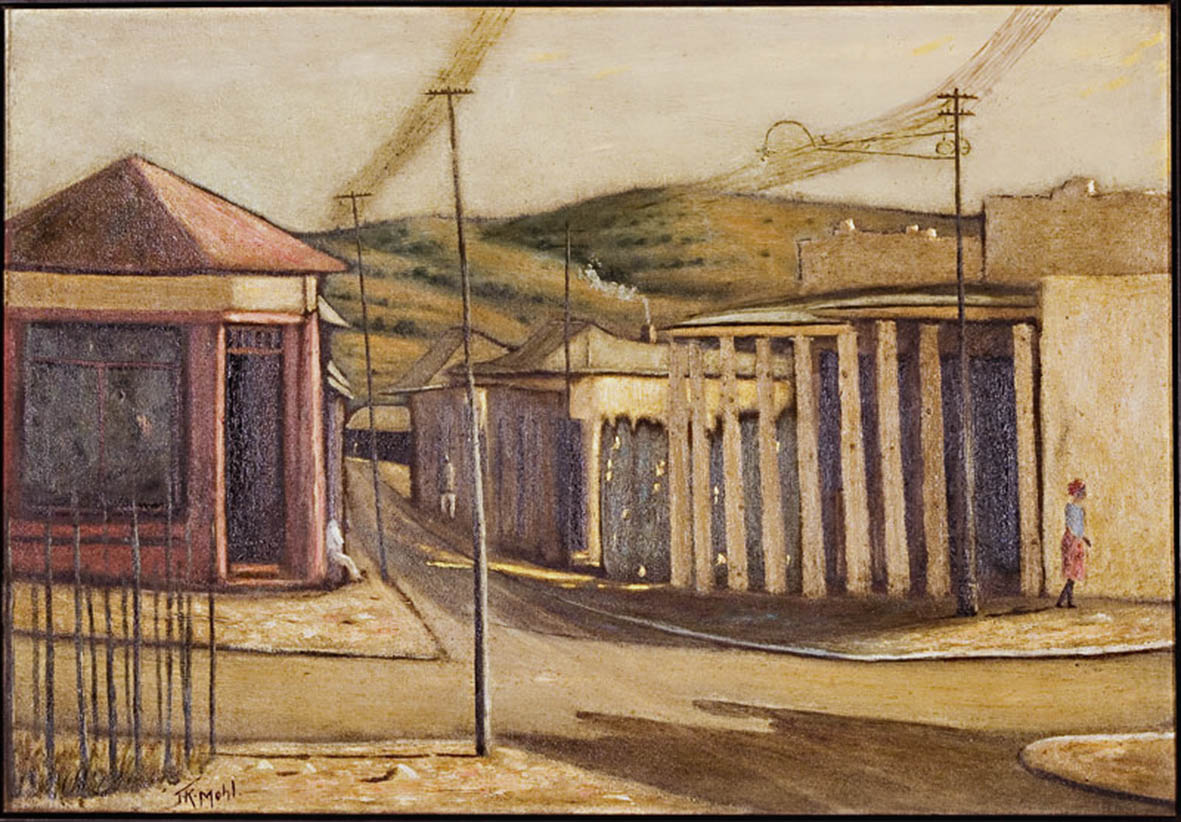

Sophiatown, Corner Rey and Edward Street (John Mohl)

Since contemporary African art has been making steady rounds on global art circuits, the late great curator Okwui Enwezor, in a text coauthored with art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, saw this as less of a “change of heart about the artistic competence of marginal regions” but more of a giving in to global pressures. Those pressures, to some extent, are owed to African and diasporic artists, whose creative and critical efforts have forced or invented different boundaries in the past century.

A Black Aesthetic: A View of South African Artists (1970-1990) unwraps these efforts in this modest exhibition of South African modern expressions and their aesthetic mutations that have given our visual arts their unique and complex features. It includes what we now can consider “traditional” visual arts objects, such as sculpture, paintings, drawings and variations of printmaking media. Its elaborate list of artists includes the early-to-late modernists Ernest Mancoba, Gerard Sekoto, George Pemba, Gladys Mgudlandlu, Selby Mvusi, Dumile Feni, Cyprian Shilakoe, Dan Rakgoathe, Charles Nkosi and so on. With perhaps the exception of a few pieces borrowed from Johannesburg Art Gallery and the Standard Bank corporate art collection, a large portion of these artworks comes straight from Fort Hare’s De Beers art collection.

Senegal Woman (Gerard Sekoto)

It’s from this collection that anthropologist Professor EJ de Jager, in 1992, put together his widely renowned exhibition Images of Man: Contemporary South African Black Art and Artists. There are notable omissions and additions from De Jager’s rather black male-dominated show, as A Black Aesthetic attempts to carve its own path. Yet, a contemporary iteration of such collections (of black modernist art in general) demands far more than nitpicking through the curatorial misadventures of the De Jagers of this world to avoid re-inscribing them.

That the show prides itself on not following any chronological order in its instalment is commendable, but on inspection this tactic seems more like an ornamental feature than a true depiction of the exhibition.

In it, one espies a certain comparative cross-generational chronology, precisely in how it separates the early modern artists from the late modernist artists. This manoeuvre can also be seen in De Jager’s show. It is especially palpable upstairs, in the concentric positioning of the early pioneers (Mancoba, Mohl, Pemba and Sekoto) situated in the centre, whereas succeeding generations unfold unevenly (read: uncritically) on the outer walls. The problem with this framing is that it tends to box these pioneer artists in a mythic age, confining their works to fixed, unchanging temporalities.

Yet this critique is about more than just the flawed categorisation of particular figures within accepted art historical time frames; it is also about misapplied efforts of African modernity, by inadvertently packaging it neatly within familiar parameters, when it resides restlessly within these pristine binaries. It’s always interesting to see how genealogies and tendencies of Black Aesthetic practice, omit situating white South African artists as students (as opposed to only mentors) and beneficiaries of black artistic expressions.

The recent Black Modernisms show at Wits Art Museum, of which Mdluli was among the key dissidents, raised questions more complex than simply the tokenisation of black intellectuals or the absence of notable black modernists. The latent point, it seems to me, was to think of African modernities not only as retrospective currencies (things of the past), but also as a mutating and prospective operation that offers the present a historical mandate.

For example, that A Black Aesthetic excludes substantially more black women artists because their inclusion requires a “much larger inquiry” (only to be attended to in the future), or that the show avoided “inventing” women in a collection that initially excluded them is a duplicitous point, considering the extensive additions to De Jager’s initial omissions. Judging by the exclusion of coloured and Indian artists in the show, what is also troubling is that what is black for A Black Aesthetic appears to be discontinuous with Black Consciousness. Instead it inadvertently ratifies De Jager’s ethnographic focus. As a result, the show not only ends up serving to echo De Jager’s androcentrism (placing the male at the centre), it also rescues some of his shoddy dispositions.

Additionally, one must wonder what the endgame is in the choice of the indefinite article “a” (black aesthetic) as opposed to the definite article “the”? Does the lack of specification raise an issue occluded or missed in conventional discourses on the black aesthetic as a philosophical inquiry? These seemingly pedantic questions seem to not bear any consideration in the show’s conceptualisation, let alone feature in the show’s paraphernalia — not even the curator’s note.

Furthermore, the show rummages around art from the Black Consciousness Movement era — as seen from its title — and this centralisation of another category is given neither explanatory depth beyond the simplicity of a muddy periodisation nor a brief elaboration on how it relates to concepts such as black theology, black abstractions, and township art.

What is really meant by Black Consciousness art? Is it simply black artists’ work done in the 1970s, or is it a formal characteristic that indiscriminately travels throughout the 1970s, somewhat in conversation with the ideological turn of the time? These questions certainly didn’t matter much for De Jager, because for him the late 1960s produced a homogenous artistic form that he simply condensed to the deprecatory phrase “Township Art Movement”.

It is the presupposition of such a labelling that produces the colonial mentality of control of black bodies and their enunciatory power. Thus, in his 1973 study, Contemporary African Art in South Africa, De Jager explicitly writes that “township art has not developed an awesome technical and intellectual power that cannot communicate with the common man; its creative motivation derives from communication rather than technological considerations”.

Regrettably, even the catalogue accompanying the show misses the opportunity to satisfactorily address these concerns. Mdluli’s piece in the catalogue, alongside Zakes Mda’s rather insipid article, leave more than a lot to be desired. Though well bound and prestigious, the book could have benefited extensively had the curator considered a more eclectic and rigorous cluster of scholars and intellectual contributors familiar with the subject area.

Lastly, perhaps we need to view curating not as the oversubscribed definitional and emblematic notion of “cure” but rather as a certain form of authorship and intellection. Maybe then, curating will require more sophistication than managerial skills and an exercise in rearranging the furniture. A Black Aesthetic is definitely a welcome intervention and a feast for the South African public impatient to learn about its cultural heritage, but it robs us of the quality and rigour that would inspire critical curiosity and verve.