Deconstruction: The Sanral site in Stutterheim and WBHOs Saldanha Project illustrates the type of intimidation being meted out by disruptors demanding a stake in projects.

They have been dubbed criminal, and labelled the construction mafia. Their proponents believe they are legitimate agents of “radical economic transformation”. It is often unclear where the line between armed violence and genuine demands for access to economic opportunities falls.

What is certain is that about 183 infrastructure and construction projects nationwide, valued at more than R63-billion according to one industry body, have been hindered — often by violent disruptions led by entities claiming to be local community or business forums, demanding a stake, typically 30%,in projects.

The phenomenon emerged in the Durban area of KwaZulu-Natal and began hitting the headlines in 2016. It has since spread across the country at a time when the construction sector is in dire straits — a series of major players have filed for business rescue or have reported depressing financials.

State infrastructure projects have been the worst hit with the likes of the South African National Roads Agency (Sanral) seeing more than 60 projects affected to a varying extent, including its R1.6-billion Mtentu bridge project, expected to be the highest bridge in Africa, and a road contract near Stutterheim. Both are in the Eastern Cape.

But private sector projects are not immune from destructive actions by people demanding work. A R2.4-billion German oil storage investment, being built by Wilson Bayly Holmes-Ovcon (WBHO) in Saldanha Bay in the Western Cape was halted in early March after “armed gangs” demanded a stake.

Rise of the ‘business forum’

Roy Mnisi,executive director of Master Builders South Africa (MBSA), said that although the phenomenon started in KwaZulu-Natal, it has spread into other provinces, including the Eastern Cape, Gauteng and Mpumalanga. He spoke to Mail & Guardian en route from Mbombela (Nelspruit), where the construction of a fresh-produce market has ground to a halt because the contractor “cannot work”. “It’s happening everywhere,” he said.

Mnisi explained that, typically, a business forum will arrive on a site to demand a 30% stake in a project. Occasionally, they may represent legitimate local emerging contractors who can offer services to a project.

Butin many cases, he said, they demand what amounts to “protection fees” — essentially, 30% of the total contract value in cash to prevent other, similar forums from arriving on site and stopping work altogether.

In other instances, he said, a main contractor may already have sub-contracted 30% of the work, sometimes more, to black emerging contractors in an area.

“But as long as [those local contractors are not] them, they are not interested,” Mnisi said. “The manner in which this has been allowed to happen is purely criminal.”

As far back as 2016, MBSA began holding discussions with forums in KwaZulu-Natal. But so many similar bodies have emerged, in so many different areas, that talks with them achieve little. When consultations with one forum end, another will arrive on site and the process has to begin all over again, he said.

Mnisi is careful to distinguish between legitimate efforts by people or groups wanting to participate in major development projects in their area, and criminality.

He believes that the demands for a 30% cut in projects come from a misunderstanding of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act and its associated regulations, promulgated in 2017.

The regulations were aimed at promoting the inclusion of designated groups in state contracts, including black South Africans, women and people with disabilities, through subcontracting on government tenders.

The regulations also require organs of state to outline the extent to which a tender will be awarded on the basis of functionality — or the ability of a company tendering to provide the specified goods and services. The qualifying criteria for functionality may not be so low that it jeopardises the quality of goods or services provided or so high that it is “unreasonably restrictive”.

Late last year the treasury condemned the “abuse in certain provinces and municipalities” of the regulations to extort contractors under threat of work stoppages.

But Mnisi argued that the efforts aimed at truly transforming the economy are being misused. “We know we have a long way to go towards the transformation of our economy … but it seems, in this country, we have let thugs take advantage of that and use it to their own narrow interest.”

An industry under siege

A common industry complaint has been the failure of law enforcement and government agencies to adequately deal with these events when they happen. And although public infrastructure is damaged or projects delayed for months, ramping up their costs, small black businesses are suffering too.

Webster Mfebe, the chief executive of the South African Forum of Civil Engineering Contractors (SAFCEC), wrote a letter to President Cyril Ramaphosa last month pleading for government intervention. He cited the example of the 2016 killing of a Durban construction company owner who was shot when he refused “disrupters” a stake in a tender he was awarded. Mfebe told the M&G this week that there has been no progress in the case, despite the police force’s knowledge of the incident.

In his letter, Mfebe describes two recent incidents — Sanral’s Stutterheim project and WBHO’s Saldanha Bay project — as a “war zone”. Images of the Saldanha Bay project reveal a scorched landscape, with rows of vehicles roiling in flames, and torched buildings. The letter includes a description of how contractors fled into the veld to escape “armed gangs”.

According to SAFCEC’s data,more than 183 projects, valued at R63.4-billion, have been disrupted or halted by such acts, the majority of which are state schemes.

“Violence begets violence. When people have seen that extortion methods yield results, they mimic the same tactics and strategies,” Mfebe said, referring to the spread of similar incidents across the country.

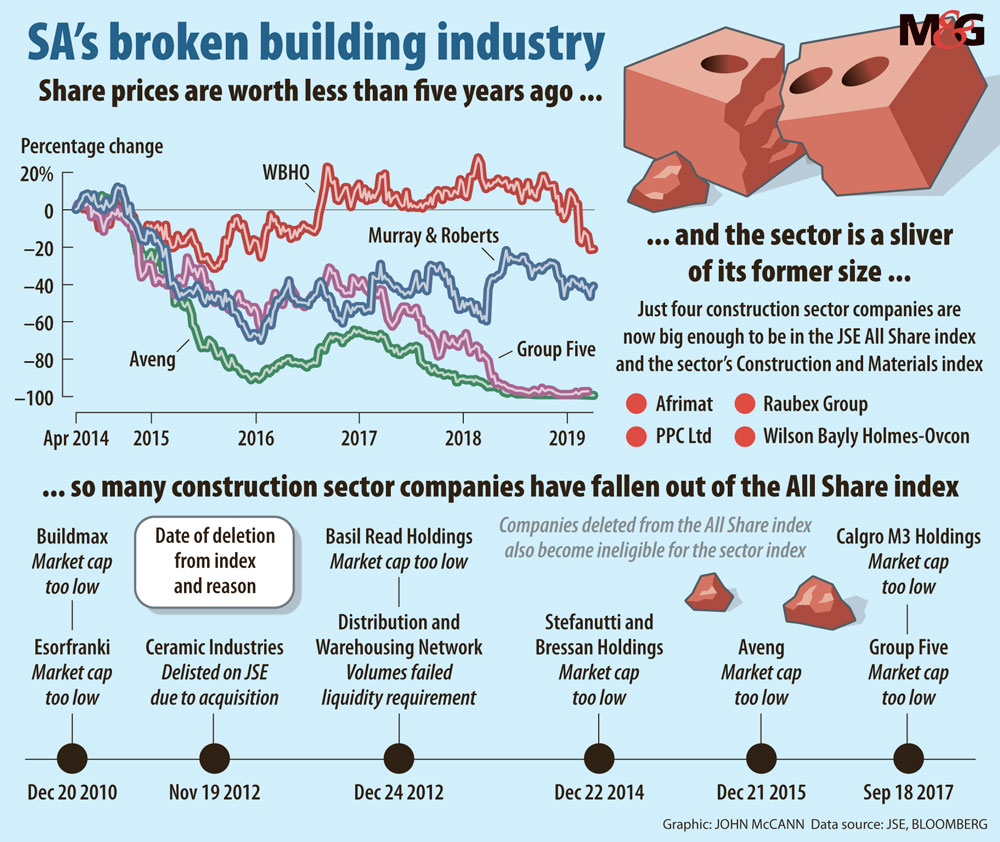

This is happening in the context of a construction industry that is in “an accelerated state of decline”. Over the past decade, the value of JSE-listed construction firms has declined by 71.8%.

The JSE’s construction and materials indexhas shrunk to just four constituents. Since 2012, firms such as Basil Read, Group Five and Aveng’s market caps shrank to levels where they were automatically excluded from the JSE’s All Share Index and thus the sector index. Both Basil Read and Group Five are in business rescue.

Public infrastructure budgets have been slashed,Mfebenoted, going from R947.2-billion in 2017-2018 to R834.1-billion in 2018-2019. There are almost 100 000 construction businesses in the sector,87% of which are entry-level businesses, Mfebe said. The ever-shrinking pool of available construction work, he said, has become fertile ground for gangsterism, state capture and a ruthless “survival of the fittest” mentality.

Industry bodies have encouraged their members to interdict groups that violently disrupt work on construction sites. But, despite SAFCEC members having launched some 51 court interdicts, to his knowledge, not a single person has been charged and the message being conveyed is that legal instruments carry no meaning, Mfebe said.

Apart from legal means, the alternative is for construction firms to pull out as their costs spiral and their losses are compounded. Many public entities, typically the clients in these cases, simply charge penalties for standing time and delays on projects as contractors take responsibility for the security of a site.

Contractors are simply not equipped to deal with these kinds of disruptions, Mfebe said.“They are trained to build infrastructure, not [for] warfare.” Allegations of armed gangs brandishing automatic weapons is a key reason this requires the intervention of a multi-disciplinary task team, which is intelligence driven,he added.

Other construction industry participants have attributed the government’s perceived lack of action to its greater inability to effectively deal with social and service delivery protests. But Mfebe believes there are more sinister reasons at play, citing allegations that some of the business forums are used as “mobilisation instruments for certain politicians at local, provincial and national level”.

But, he said, there are genuine entrepreneurs and groups of residents in an area where a project is taking place who want to get involved.“We can’t paint everyone who wants to be involved as gangsters and thugs.”

Transparency is key

It appears that the emergence of formal, recognisable structures has coincided with claims of declines in violent site disruptions. Two formal bodies routinely come up in reports of violent disruptions on sites, notably in KwaZulu-Natal —the Delangokubona Business Forum and the Federation For Radical Economic Transformation (FFRET), which established itself as a national representative body for business forums. The federation denied allegations of violence and criminality and dismissed the characterisation of its members as “mafia”(See “FFRET: We are transforming as we transform”). Requests for comment from Delangokubona were not answered by the time of going to print.

The federation established itself in late 2016.According to Mfebe, since it has formalised its operations and established itself as a recognisable body, there has been better communication with the industry and a marked reduction in site disruptions in the province. What is more, where there has been a resurgence of site disruptions, the federation has played a role in diffusing tensions.

But as business forums have appeared on construction sites around the country, it is difficult to separate out the legitimate from the unlawful. Ronnie Siphika, an academic and the chief executive of the Construction Management Foundation, attributes the spread of business forums to the growth of FFRET.

“There is no system in place to determine exactly who their members are,” he said.

It is very difficult to understand how their forums are formed and the informal nature of what they do. This contributes to why they are spreading “so quickly”.

Desperation

Sanral has keenly felt the effects of protests and violence on its projects.

Spokesperson Vusi Mona said it is deeply concerned about the threat to the safety of staff, its contractors’ staff and its buildings and equipment. Buthe denied that Sanral is unduly punishing contractors faced with these violent invasions. Penalties are dealt “with as per the contract on the merits of each case”.

In Sanral’s experiences, the sheer desperation for jobs, some income or some opportunities, lies at the heart of much of the “mafia-like” behaviour.

“It remains a challenge for us that on many of our construction sites, previously disadvantaged South Africans appear and demand a piece of the cake,” said Mona.

Although some “go outside the rules” when making demands, said Mona, Sanral is at pains not to label “stakeholders in a derogatory manner” by using terms like the “construction mafia”.

Nevertheless, it condemned “criminality which [tends] to divert genuine calls for proper,broad-based participation”.

“The lessons that we, as Sanral,and other state bodies should take from this is that open and transparent dialogue is key,” said Mona

FFRET: We are transforming as we transform

Two organisations are often mentioned in the same breath as allegations of a construction mafia.

The Delangokubona Business Forum and the Federation For Radical Economic Transformation (FFRET), which has established itself as a national representative body of business forums, have routinely been associated with past violent disruptions of construction work in KwaZulu-Natal.

Both have been linked in media reports to, among others, a halt in construction on controversial businessman Vivian Reddy’s multibillion-rand Oceans development in Umhlanga last year. And both have reportedly been the subject of an interdict by the KwaZulu-Natal provincial treasury and its finance MEC, Belinda Scott.

The federation is headquartered in Durban’s plush suburb of Mount Edgecombe and its social media pages are peppered with the hashtag #RETManje (radical economic transformation now), and demands for greater inclusion in South Africa’s economy.

But FFRET secretary general Robert Ndlelathis week distanced the federation and its members from the moniker “construction mafia” and the spate of violent site invasions that have spread across the country.

Ndlela said the federation was created to fight economic exclusion and act as an umbrella body for the numerous business forums that represent emerging entrepreneurs. Through the federation, forums now have a co-ordinated way of approaching economic opportunities on contracts.

Ndlela said that since the formation of FFRET, there has been a reduction in site invasions in the Durban area and the methods employed by the federation in the region should be looked atas a model for encouraging broader participation in projects and stemming disruptions.

These include the formation of project steering committees that comprise representatives of developers, main contractors, business forums, ward councillors and other stakeholders. Where these exist, Ndlela says “chances of interruption are almost zero”.

The federation is closely tied to Delangokubona, sharing a number of leaders,but the latter is not what it used to be, Ndlela said.

There are, however, “copycats”who employ the tactics previously associated with Delangokubona and other forums that existed before FFRET and which “our members are no longer doing”. He maintains, however, that there is no proof the Delangokubona and other federation members have employed violence.

It’s only now, he says, that shocking pictures have surfaced from, for instance, the Western Cape, and accounts of violence have emerged, “which we as FFRET seriously, seriously condemn”. Economic participation must happen, he said,“but within the confines of the law”.

Industry players, however, believe the failure by authorities to act on site invasions in KwaZulu-Natal has contributed to the use of similar tactics nationwide —they were shown to work and there have been no repercussions. Ndlela said that some of the allegations are “simply not true”.

Ndlela labels extortion by forums demanding protection fees to the value of 30% of projects as “daylight robbery”. But, equally, he dismisses allegations that where forums are included on contracts they do shoddy work or lack skills. He says the federation’s extensive network of members —which he claims is now at 4620 around the country — have the requisite skills.

To promote and emphasise the rule of law,the federationis hosting asocioeconomic justice dialogue which will include the chief justice, the public protector and the national director of public prosecutions. Ndlela said the aim is to bring people together to discuss how to transform at the same time as “we protect our democratic institutions”.

Delangokubona did not respond to requests for comment.