Intolerance: The Ponsonby Masjid, built in 1979, was Aucklands first mosque. (Hannah Peters & Phil Walter/Getty Images)

When the Muslim Association summoned Ahmed Said Patel from Gujarat to Auckland, New Zealand,he had a rough idea of what his responsibilities would be: Auckland’s growing Muslim community needed his services. They were without an imam, and their children were without a Qur’an teacher.

So, without his wife Rabia, Patel boarded the SS Strathmorein Mumbai on September 18 1960 and arrived in Auckland 22 days later.

“It was an absolute sacrifice for my grandfather to come to New Zealand all the way from India, without knowing how things would go,” says Patel’s 24-year-old grandson, Aslam, who also does community work and teaches children at the Birkenhead Islamic Centre. “He knew his purpose, but had no idea whether he would be successful or not. And he probably didn’t know the extent of the job that he had to do.”

When Patel arrived, he found that the New Zealand Muslim Association could not pay him, so he would set off to work at 7am every day — first at a wool store, then at a rope factory and then as a welder and packer at an electrical utilities factory. Only after work, in the late afternoon, would he visit the home of whomever he was teaching that day. “My grandfather believed that Islam is not only for yourself but also for everyone around you, and when you give assistance to others, that made you a better Muslim,” says Aslam.

The foundation for the Ponsonby Masjid, New Zealand’s first mosque, was laid in Auckland in March 1979, and the Federation of Islamic Associations of New Zealand was established that April. When the mosque was completed a few years later, Patel was its first imam. He stayed in that role, while continuing to work, until 1987, when he had a stroke.

Inside Ponsonby Masjid: Last month a gunman shot 50 worshippers at this and another mosque in an act that shook the country. (Hannah Peters & Phil Walter/Getty Images)

Inside Ponsonby Masjid: Last month a gunman shot 50 worshippers at this and another mosque in an act that shook the country. (Hannah Peters & Phil Walter/Getty Images)

“Weddings, births, deaths — my father was the person the community turned to whenever these big events took place,”says Patel’s son, Azhar (45).

Although Patel oversaw the first formalisation of an Islamic community in New Zealand, he and his fellow Muslims were far from the first in the country.

Until as recently as 10 years ago, conventional wisdom said that the first Muslims arrived therein 1874. The census at that time recorded 15 Chinese Muslims in the South Island — presumably miners after the discovery of gold — although four years later, there were no traces of them.

“The story is an evolving one at the best of times,”says Abdullah Drury, who has been documenting the history of Islam in New Zealand since 1996.

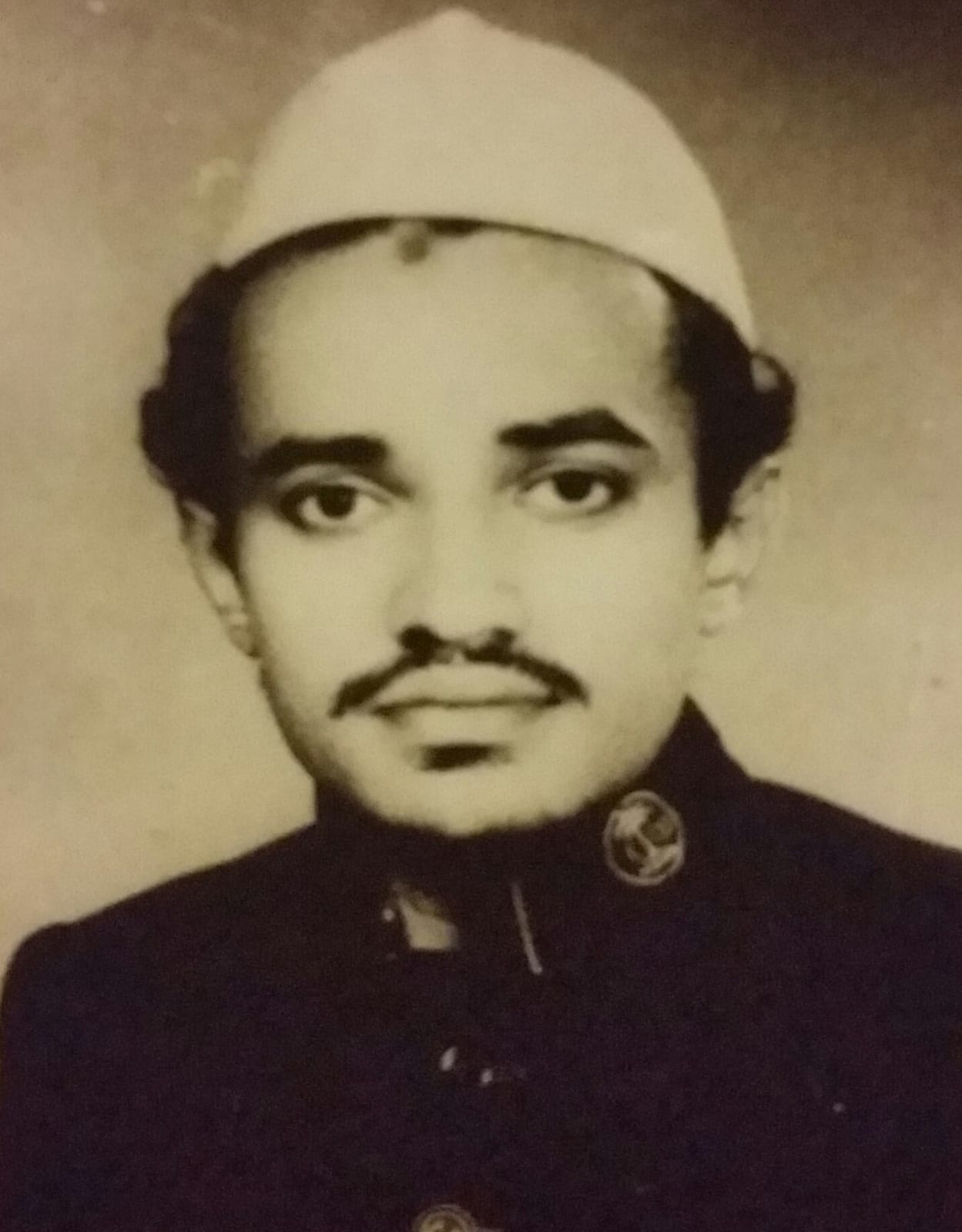

Ahmed Said Patel, the Ponsonby Masjid’s first imam, though Muslims have been recorded in New Zealand for centuries. (Photos: Hannah Peters & Phil Walter/Getty Images)

Ahmed Said Patel, the Ponsonby Masjid’s first imam, though Muslims have been recorded in New Zealand for centuries. (Photos: Hannah Peters & Phil Walter/Getty Images)

Research has now uncovered earlier traces of Islam on the islands. Also called Mahometans, Mussulmansor Mohammedans, there are records of Muslim settlement in the country throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

The first recorded Muslims in New Zealand were workers aboard a French ship in 1769. In 1854, a servant named Wuzerah came to the country aboard a ship from India that belonged to a British imperialist.In the 1870s, Wuzerah transported and laid the stones for the foundation of the Christchurch Cathedral — something Drury suggests may be the first instance of Muslim/Christian interfaith activity.

Muslims brought from India were considered subjects of the British empire and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, which granted Britain sovereignty over New Zealand, enshrined freedom of religion.

The 19th century saw a smattering of other Muslim presences recorded before and after the Chinese miners. In 1861 an Omani sailor (“a remarkably black man”) was recorded in the South Island, as were a father and son from Turkmenistan. In the early 1900s, with the increase in trade, a Gujarati Muslim community was established in Auckland.

In 1951, the first large group of Muslims arrived when refugees from Eastern Europe came to New Zealand, their pale skin allowing them to assimilate with ease. From 1980 onwards, the Muslim population increased with the arrival of refugees, immigrants and students from Asia, Africa and the Middle East, as well as conversions to the faith.

“The one consistent feature of the Muslim minority in New Zealand is the fact that it has always been made up of several overlapping, interactive and evolving communities, and this provides some clues as to future prospects here,” says Drury, who converted to the faith after developing an interest in it while at university. “I see New Zealand Muslim history as an integral part of the rich and complex fabric of this country’s past.”

Although New Zealand’s 2013 census puts the number of Muslims at roughly 46000 — 1.1% of the population — Muslimleaders believe the actual figure is closer to60000. There are more than 30 mosques inthe country serving Muslims, who,despite having cultural, ethnic, linguisticand denominational differences,all serve the same God.

“I’m Maori as can be,” says Musa “Kevin” Taukiri (56),who has been Muslim since 2001. The father of 10 belongs to a high-chief line in Maoridom and is leader of the Hourua tribe. He is the Federation of Islamic Associations of New Zealand’s national dialogue co-ordinator for tangata whenua (land affairs), where he is involved in land treaty negotiations between Maori and the government. Professionally, he is part of efforts to certify exports of lamb and beef as halaal.

Taukiri says he has been able to marry his Maori and Muslim identities. “As a Maori Muslim you have to know your boundaries, but you are never excluded from being who you are. I am respected in both communities, and my children take part in village life.”

Janifa Bhamji (39) is the daughter of a Maori mother and Fijian-Indian father. “Similar to Muslims, Maori do prayers for everything,” says Bhamji, who works for the Maori Mental Health Organisation in Christchurch. “The principles for both are very similar: give your heart in everything to make people feel at home. Keep good relations with people. And have good intentions when you do things, to guarantee a good outcome.”

Zimbabwean-born Sabah Rahman (22) says that identity as a Muslim New Zealander means community. “As separate as I felt from other aspects in my identity, I never experienced that with my religion. It’s a fuller, deeper connection, and I think that’s because of our Kiwi values,” she says.

Although there may be tolerance for the most part, there remain differences that the community continue to work at. Latifa Daud (26), who is involved in many community initiatives, including a drive to improve women’s access to some mosques in Auckland, says: “I think that as the Muslim community in New Zealand we have some soul-searching to do internally as we move forward, especially after [the] Christchurch [killings].”

On March 15, 50 people died when a lone gunmen attacked two mosques in the city.

Zach Penman (29)converted to Islam when he was 24. “The culture in New Zealand is very secular, and I was a product of that,” he says. “When I was 21, I became conscious of God while I was doing postgraduate research on contemporary Western moral philosophy. I’ve never been this happy or successful — my character has improved, and my family relations are stronger than ever. As a white man, I go from being invisible to hyper-visible in my Muslim identity when I wear thobe [a robe]or if I am out with my wife, who is black and wears a headscarf. I think we look cute, but apparently we look menacing to some white New Zealanders.”

In New Zealand, national, cultural and religious identities are all tied to one another. These overlapping identities have undoubtedly strengthened the Kiwi Muslim community, but also amplified its suffering in the wake of the Christchurch attacks.

When Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern quoted the Prophet Muhammad a week after the killings, she reiterated this.

“The believers in their mutual kindness, compassion and sympathy are just like one body,” she said outside the Al-Noor mosque on March 22. “When any part of the body suffers, the whole body feels pain.”