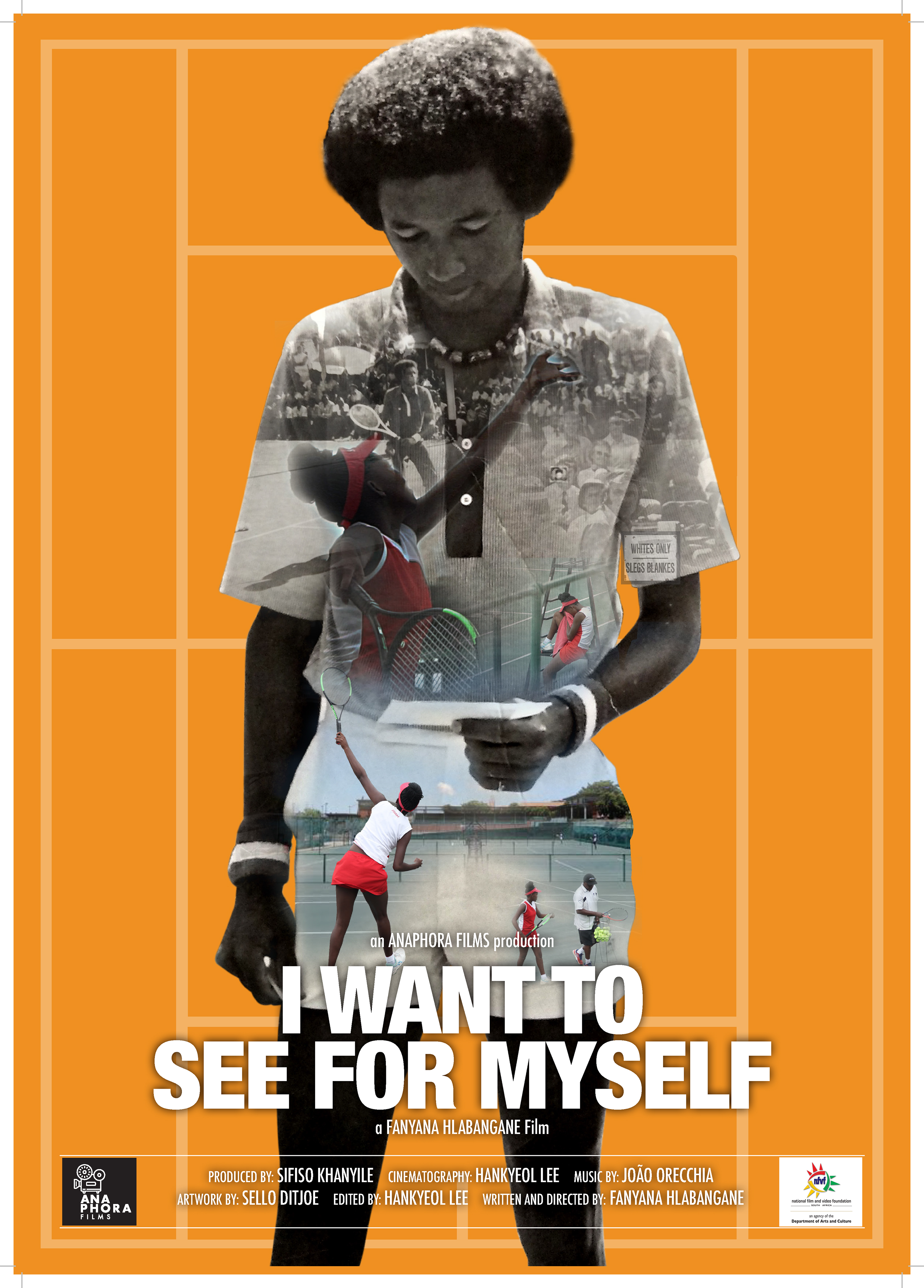

Best serve: A documentary layers old footage of US tennis star Arthur Ashe with scenes of Amukelani Mokone and the Arthur Ashe Tennis Centre in Soweto. (Chris Smith/Popperfoto/Getty Images)

It was 1973. Steve Biko was months away from being banned by the apartheid government. Armed with sanctions that ranged from a halt on weaponry imports to a ban on participating in the Olympics, the world had turned its back on the South African government.

It was during this period that the government granted American tennis player Arthur Ashe a visa to participate in the South African Open. He was the first black tennis player to win the singles titles at Wimbledon, the US Open and the Australian Open.

Growing up in a segregated Virginia, Ashe was aware of sanctions and the apartheid regime’s effect on black tennis players. He noted the offence taken by anti-apartheid activists but he rejected the plea that a sportsman of his stature should not participate in the open. He responded with a simple: “I want to see for myself,” referring to the living conditions of black people.

During his visit to South Africa, Ashe encountered young people who regarded him as a hero. Those of them who were aspiring tennis players could only dream of following his path. The South African Lawn and Tennis Union of the time severely limited their access to the sport.

Aware of the obstacles black athletes faced, Ashe built the Arthur Ashe Tennis Centre in Jabavu, Soweto.

Four decades later, the centre still stands as a monument for opportunities and equality through sports.

One of its stars is Amukelani Mokone, whose efforts have earned her a scholarship at one of Johannesburg’s prestigious high schools, a trip to Wimbledon and a role in an award-winning documentary.

I Want to See for Myself, which recently won best documentary at the Dieciminuti Film Festival in Italy, was written, directed and produced by filmmakers Fanyana Hlabangane and Sifiso Khanyile in 2018.

With the narrative focused on Mokone and her coach, the documentary captures the effect the centre has had on Jabavu residents.

Oupa Nthuping has been coaching tennis at the centre for 10 years and he has coached Mokone since she was seven.

Using archival and original footage, Hlabangane and Khanyile present this story in a sandwich format. Nthuping and Mokone sit neatly between footage of Ashe speaking on segregation and access in tennis.

With a limited time frame of 10 minutes, Hlabangane and Khanyile use such tactics to show, rather than tell, a layered story.

It is about access, spatial planning, progress, the estrangement that black born-frees have to navigate in their everyday lives and the role of skills development — just as much as it is about tennis.

The filmmakers use natural sound, colour, framing and silence as storytelling tools over and above what is relayed through titles and sound bites from the interviews with Mokone and her coach.

Consider how the sports centre is introduced to us using footage from 1977 — when it first opened its doors — before exchanging the same scene for one that was shot recently. We see the centre’s surroundings developing from those of devoid of foot traffic into a congested residential area.

Nthuping’s interview is set in the tennis centre, where a series of shots suggests he is alone. His opening remarks touch on the difficulties that come with playing tennis: players need rackets, shoes, balls and well-maintained courts. He pauses. Then, through a series of shots, we watch him coach, clean the centre and quietly do repairs.

With regard to the estrangement of black born-frees, I Want to See for Myself moves between Jabavu and St Mary’s School, in Johannesburg suburbia. The scenes in Jabavu are up close and detailed. In contrast to this, scenes of Mokone at her school are shot through a window or at the door as if the lens was not granted access into the space.

Mokone adds to this by saying she knows she is not like her classmates, who are not there on scholarships.

Although I Want to See for Myself is pressed for time, it does not rush to get its message across. It pauses to let the viewer reflect and anticipate the next scene. It does not bombard them with facts, experts or timelines. Instead, it takes its time to explore national issues in a manner that one could argue has a more lasting effect than the long-form and subject-heavy format that documentary often takes.