Looking back: 'Albert Adams An Invincible Spirit' exhibits the artists seminal works such as The Captive (1952)

Although Albert Adams has had a number of posthumous retrospectives, the current one, entitled Albert Adams — An Invincible Spirit, may just be his most important, especially if timing — straddling Freedom Day, South Africa’s elections and the publishing of his biography — is factored in.

The exhibition, at the Wits Art Museum (WAM) until May 25, is curated by Marilyn Martin and celebrates 90 years of the exiled artist’s birth. It once again encapsulates an oeuvre spanning more than 50 years.

Comprising paintings, drawings and prints, including several key works such as South Africa 1959, from the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s collection, the works highlight the “universal” scope of Adams’s political outlook while speaking to the particular effect of apartheid on South African society.

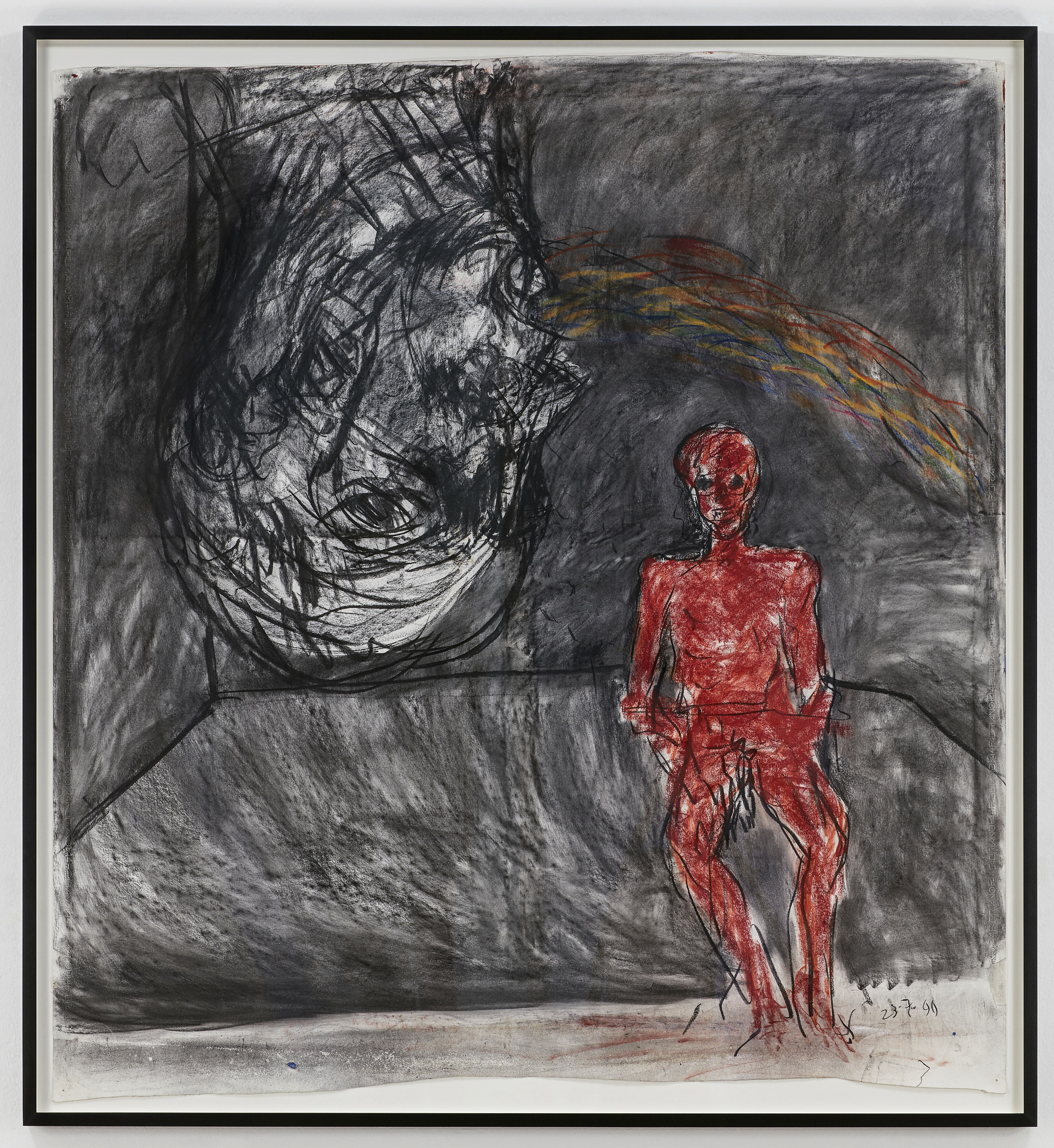

A particularly pointed image in this regard, which viewers confront quite early on in the exhibition, has to be the charcoal and pastel on paper work, Red Figure (1999). Standing 1 640cm x 1 500cm in dimension, an upended, heavily lined, greyish head spews out a rainbow-like flame (or flame-like rainbow) within range of an almost skeletal figure rendered in red on a backdrop suggesting Table Mountain. The work forms part of the artist’s cherished Incarceration series which, given the timing of the exhibition, is pregnant with symbols of South Africa’s social maladies and the country’s thwarted potential.

Red Figure (1999), charcoal and pastel on paper work. (Albert Adams)

For Martin, a curator of several of Adams’s shows since meeting the artist during his visits to the country, this particular show (which coincides with the publishing of his biography by Elza Miles) is of particular visual significance.

This is because the spacing of the WAM allows the viewers to appreciate Adams’s knack for serialising his work, the three tiers of the building lending themselves to capturing a sweep of the artist’s areas of focus.

Of course, with a large portion of his work in varying hands, viewers are witnessing broad strokes and just a sample of his prowess.

Significantly, says Martin, the exhibition features few of the artist’s prodigious self-portraits and his etches.

“With other retrospectives, such as at the Rupert Museum in 2017 [which was cocurated with Robyn-Leigh Cedras], we have many of the same key works, but this has a more developed schematic outline of different phases. With the Rupert Museum, everything had to go to one big room.”

The show begins with a series of portraits on the lower floor, including those of the artist and a striking, colourful rendering of his studio in London’s Delancey Street.

Introspective: The show begins with a series of portraits, such as Portrait 2 (1950), however many of Adams’s prodigious self-portraits and etches are not available for exhibition. (Albert Adams)

The main tier covers early works, drawings in expressionistic styles, very pointed political works such as Untitled (Four Figures with Pitchforks) (1950), key works such as the previously mentioned, Picasso-recalling triptych South Africa 1959 and South Africa 1958 to 1959 (Deposition) as well as other seminal works such as Sleeping Man at Rondebosch Fountain — a large-scale oil on canvas depicting a headless, slouching figure with smudged legs passed out on a step.

Here, mood, palette, technical and thematic range and variations in scale may hit the viewer like a fusillade, with familiar works and Adams’s variety of influences developing full power from the manner in which the works converse with each other.

The upper level of the exhibition encompasses works from the Celebration series (Adams’s lyrical and inventive look at the Kaapse Klopse) and works that feature apes, a theme the artist returned to, albeit decades later.

Born to an Indian father and a coloured mother in Johannesburg in 1929, Adams moved with his mother and sister to Cape Town at the age of four. After high school, Adams was unable to study fine art at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, being refused entry on the basis of his race.

He was later awarded a scholarship to study at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, which he did from 1953 to 1956. He then studied under the Austrian poet, artist and playwright Oskar Kokoschka, who is often credited with bestowing on Adams a particular artistic sensibility and passion for justice.

For the few years Adams was back in Cape Town before returning to London for good in 1960 (the year of the Sharpeville massacre), he worked and exhibited often, with Kokoschka sending a written message for one of his exhibitions.

Adams later taught in secondary schools in London’s East End and taught art history at the City University for 18 years from 1979.

In an article looking at a Smac Gallery retrospective on Adams, an exhibition cocurated by Martin in 2016, Mary Corrigall makes the point that “it doesn’t help that he died before giving curators enough insight into what motivated his art; so much of what we know is based on their suppositions”.

In the book Journey on a Tightrope, an exhibition catalogue that accompanied a retrospective at the Iziko South African National Gallery in 2008, little seems to be directly attributable to Adams by way of quotes or even his own writings. A concise journal featuring sparse but often visceral entries between August 1956 and July 1960 — put together by his partner Edward Glennon and Art Space Gallery in London — shows Adams to be a highly sensitive individual, navigating shame, rejection, encounters with art and a deep awareness of injustice, but resolving to do something about it.

Martin, having befriended the artist in his latter years, said during a phone interview: “He never regarded himself as a political exile. He was quite clear about that.” On the other hand, she recognises the religious themes to his works as “vectors of social and political commentary”.

Her words seem at odds with what the works quite emotively point to.

Also, Martin says, the artist was reticent about promoting his own work, noting that not much of his etchings are available, and that he was a very good printmaker.

The above is not to suggest any duplicity on Martin’s behalf but merely to highlight that Adams’s life, works and political ideas still present opportunities for further study and reframing.

The biography, which launches on the last day of the retrospective at WAM, may provide an opportunity to encounter the iceberg beneath the water’s surface.