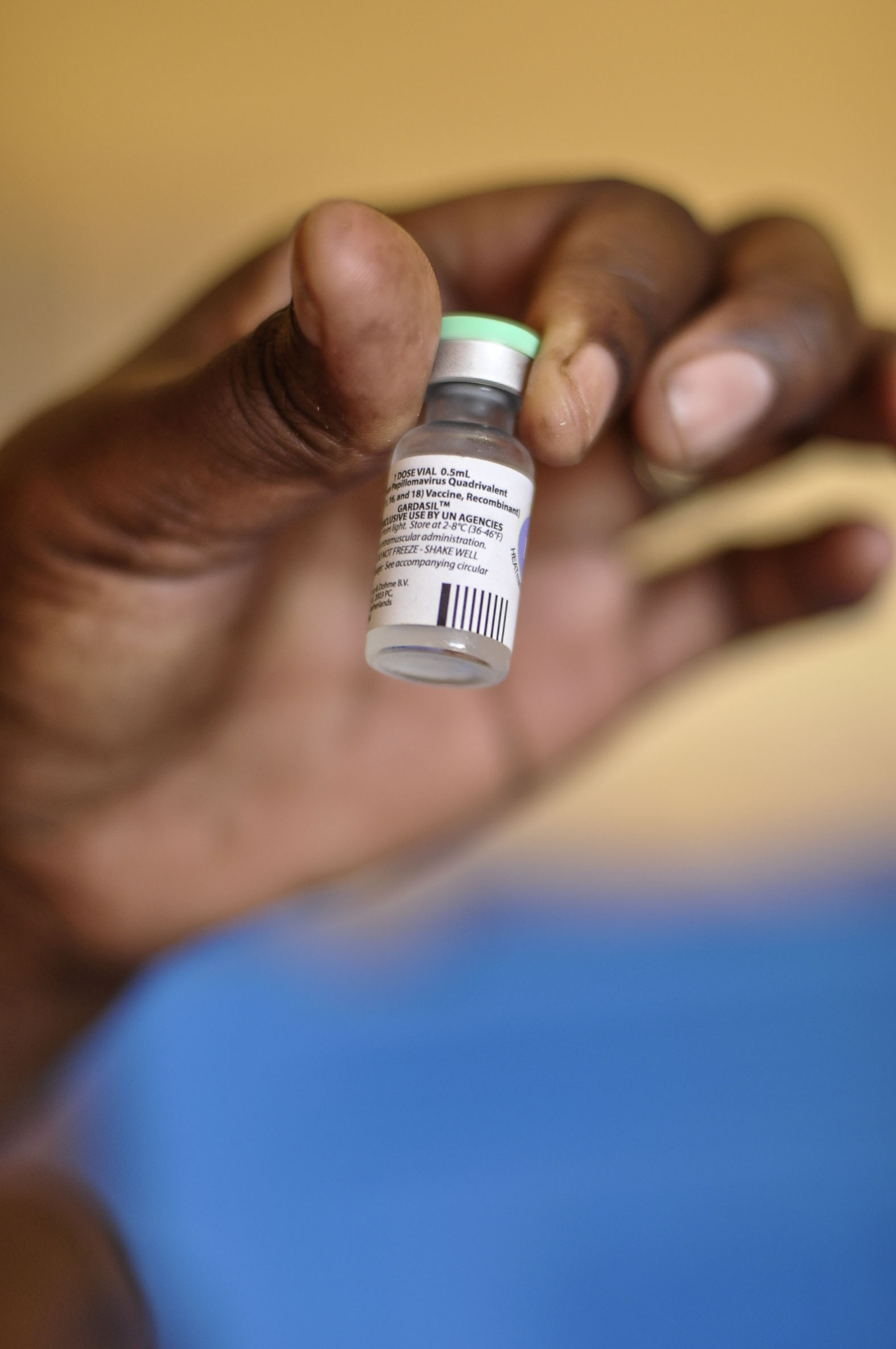

Why this country is thinking outside the box whene it comes to cervical cancer screening and the HPV vaccine. (UNICEF)

Girls begin queuing at their local school with their friends, waiting for their names to be called. Many are apprehensive. After all, most had not been vaccinated since they were babies. It’s 2013, and a new immunisation has arrived in Kanyirabanyana, a village in the northern district of Gakenke in Rwanda nestled among rolling hills and plantations growing crops from bananas to potatoes.

Unlike the 10 vaccines already offered to young children as part of the national immunisation programme, this jab is different: it’s being offered just to older girls, age 11 to 12, in the final year of primary school.

Three years before, Rwanda decided to make preventing cervical cancer a priority. The government agreed to partner with pharmaceutical company Merck to offer girls the chance to be vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer.

It was the first time an African country had embarked on a national cervical cancer prevention programme.

It was an ambitious goal. Cervical cancer is the most common cancer in Rwandan women, and there were considerable cultural barriers to the vaccination programme – HPV is a sexually transmitted infection and talking about sex is taboo in Rwanda.

Rwanda’s history also made it seem an improbable candidate for achieving high HPV vaccination coverage.

About 800 000 people died in the Rwandan genocide, and its widespread destruction left the country devastated. Coverage of most WHO-recommended childhood vaccinations plummeted to below 25% in the massacre’s wake, shows 2016 research published in the journal, Vaccine.

But within 20 years, the number of babies in Rwanda receiving all recommended vaccinations, such as polio, measles and rubella, had increased to around 95%.

Could it now have the same success with HPV?

Rwanda was the first country on the African continent to roll out the HPV vaccine. (UNICEF)

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women. There were an estimated 570,000 new cases in 2018 – and over 310,000 deaths, the vast majority in low- and middle-income countries, the World Health Organisation (WHO) says. Sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind the rest of the world in introducing the HPV vaccine and routine screening, which means the cancer often isn’t identified or treated until it has reached an advanced stage.

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV, the WHO explains.

Most of us are infected with at least one type of genital HPV at some point in our lives – usually as teenagers or young adults. In most cases, the virus is harmless and resolves spontaneously without causing any symptoms such as genital warts.

There are more than 100 strains of HPV, at least 14 of which can cause cervical cancer and a range of less common cancers, including those of the penis, vagina and anus. Persistent infection with two strains of HPV, 16 and 18, is responsible for 70% of cervical cancer cases.

The first vaccine against HPV became available in 2006. But with the excitement about the new vaccine came the realisation that not all girls would have the same chance to receive it.

It was likely that at least a decade would pass between its introduction in high-income countries and in low-income countries.

Today there are three HPV vaccines – Gardasil and Gardasil 9, made by Merck, and Cervarix, made by competitor GlaxoSmithKline and a newer version — Gardasil 9 — that was licenses in 2014. All three vaccines are highly effective at preventing infection with virus types 16 and 18. Gardasil 9 otects against nine types of HPV, which between them cause around 90% of cervical cancers, researchers estimate in a 2017 study on the vaccine published in The Lancet and funded by Merck.

Before the HPV vaccine arrived in Kanyirabanyana, 63-year-old community health worker Michel Ntuyahaga spent weeks canvassing his village, going to each of the 127 mud-brick houses to inform parents about the upcoming immunisations campaign.

Joined by a nurse, he explained to parents that if they had an adolescent daughter, they had an opportunity for her to be vaccinated against a deadly women’s disease – cervical cancer.

“I explained to parents that the cancer is a disease and that the one measure to prevent it is vaccination,” he says.

Ntuyahaga wasn’t the only person educating the community about the impending jabs.

Constantine Nyiransengiyera has been a primary school teacher in Kanyirabanyana for 13 years. In addition to teaching maths, science, French and English, she was – and continues to be – responsible for gathering all the 12-year-old girls at the local school and educating them about the HPV vaccine.

Silas Berinyuma, a leader in Kanyirabanyana’s Anglican church for more than two decades, preached about the importance of the vaccine for weeks before it arrived in the village. The church used drama to depict scenes of cervical cancer’s devastating impact and these plays go on even today.

Similar scenes were playing out across the nation in part care of Rwanda’s network of 45 000 community health workers, volunteers who are present in every village.

In Bugesera, a district not far from the border with Burundi, billboards line the roads advertising soft drinks alongside public health messages.

One says: “Talk to your children about sex, it may save their lives.”

Not far off the main road is Karambi, a community surrounded by banana plantations.

In 2013, the then 12-year-old Ernestine Muhoza was vaccinated against HPV at her school. “The teachers called just girls for assembly and told us that there was a rise of a specific cancer … and that it was time for us to get vaccinated,” she remembers.

When she went home to tell her parents about the new immunisations, they’d already heard about it on the radio and via community health workers.

Muhoza’s parents readily agreed.

But not every parent did.

Some were sceptical. Why, they wondered, would their girls be getting vaccinated at this age? Why couldn’t all girls and women receive the inoculation?

And then there were myths that the vaccine would make girls infertile.

The Community health worker Odette Mukarumongi worked tirelessly in Karambi to counteract the myths that had begun cropping up across the country. And she stressed what might happen if one day girls didn’t get vaccinated and developed the cancer.

“I told parents that a girl will go into constant menstruation – like endless bleeding – if she gets cervical cancer,” she says.

Irregular vaginal bleeding, including after sex and between periods, can be a symptom of advanced cervical cancer, the United States medical research organisation Mayo Clinic warns.

Rwandan Health Minister Diane Gashumba admits that the rumours surrounding it were difficult to quash.

“The rumours were not anticipated. But, of course, as the HPV vaccine was a new vaccine for a new target group there were many questions,” she says.

And Rwanda wasn’t the only county to have its HPV vaccination fall victim to the rumour mill. The myth has cropped up in countries as diverse as India, Tanzania and Romania in part fuelled by internet conspiracy theories, researchers found in a 2012 study published in the journal Vaccine. In Romania, scientists noted that enshrined gender roles made some mothers more willing to risk cervical cancer among their girls than risk their fertility.

There is no research to show that the HPV vaccine impacts a young woman’s fertility.

In Karambi, Mukarumongi says parents eventually “surrendered” and allowed their daughters to be vaccinated. Today, she says, mothers and fathers rarely refuse, now that they can see the widespread acceptance of it in the community.

Gashumba says that trust in the government and the integral role played by church and village leaders as well as community health workers in dispelling myths about the vaccine helped to overcome the misinformation.

“It was also about the trust the community has in the government”, she says. “That was really important – the community knows that we do not bring things that are not good for them.”

What happens after the Big Pharma drug and vaccine donations end & and big donor bucks dry up? (Shonagh Rae Heart)

What happens after the Big Pharma drug and vaccine donations end & and big donor bucks dry up? (Shonagh Rae Heart)

Rwanda and Merck’s 2010 agreement meant that the company would supply the country with HPV vaccinations for three years at no cost. As one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, Merck wanted to demonstrate that it was feasible to introduce the vaccine in low-income countries in the hope that Gavi – a global health alliance to increase access to vaccination in these countries – would take note and get on board.

“You quickly recognise that you have a vaccine that can have such a major impact in preventing cervical cancer, and the greatest disease burden is concentrated in the world’s poorest communities. You cannot, with any conscience, not come forward and make the vaccine affordable and create a sustainable vaccination programme’, Mark Feinberg says.

Feinberg is the former chief public health and science officer at Merck and was involved with the Rwanda programme. He is now the president and CEO of the International Aids Vaccine Initiative.

“The programme in Rwanda had two purposes: to get the vaccine to a population who could benefit, but also to demonstrate what was possible.

“Rwanda is an incredible country in its commitment to national health”, he explains. “If it wasn’t possible in Rwanda, we knew it wouldn’t be possible anywhere else.”

But Rwanda’s deal with the pharmaceutical company wasn’t without its critics. In a scathing letter to TheLancet, German researchers voiced “serious doubts” that the HPV programme was “in the best interest of the people”. A major issue, they contended, was that while the burden of cervical cancer in the region was substantial, there were far more pressing diseases to vaccinate against, such as tetanus and measles.

Rwanda’s then Minister of Health, Agnes Binagwaho, replied publicly in a letter co-signed by two US researchers.

Rwanda already had very high vaccination rates for tetanus and measles, the trio pointed out.

“Are the 330 000 Rwandan girls who will be vaccinated against a highly prevalent, oncogenic virus for free during the first phase of this programme not regarded as ‘the people’?” they asked.

Binagwaho, now vice-chancellor at the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, is still critical of those who called into question the country’s move to roll out the HPV vaccine nationally.

She explains: “The people who have created a backlash haven’t done their homework – they don’t know our country, they don’t know that our kids are well vaccinated with other vaccines available.”

Today, the Rwandan health ministry says 93% of girls get the shot to protect them against HPV. In a country where 96% of girls attend primary school that’s in large part because the campaign has focused on schools like the one in Kanyirabanyana, says Claire Wagner, a student at Harvard Medical School who formerly worked as research assistant to Binagwaho.

Health Minister Gashumba concludes: “We are working on our goal. We put our people first.”

Rwanda rebuilt a health system from genocide’s ashes and has the HPV vaccine campaign to prove it. (Shonagh Rae Heart)

Rwanda rebuilt a health system from genocide’s ashes and has the HPV vaccine campaign to prove it. (Shonagh Rae Heart)

Since 2006, more 80 countries including South Africa have introduced the HPV vaccine. But immunisation programmes are only one part of curbing cervical cancer deaths – the other is making sure women get regular screening to catch cancer early and treat it.

For many women around the world, also in South Africa, cervical cancer screening comes in the form of regular Pap smears. As part of the test, health workers will send a swab of cells collected from a person’s cervix to a laboratory to check for any abnormalities. South Africa’s largest medical aid, Discovery, covers one such test every three years for members, the company’s website says.

In the public sector, women who are HIV-negative get a Pap smear every 10 years although younger women can also request the service, according to its latest publicly available guidelines released in 2014.

Women living with HIV who are at a higher risk for developing cervical cancer should be screened every three years or annually if they have a positive result.

But Pap smears are labour intensive and require laboratory services not always available in low income settings. And if they are available, they’re usually concentrated around urban areas or teaching hospitals, meaning women in farther flung areas can wait weeks if not more for test results, a 2012 WHO report argues. This can cause deadly delays in treatment.

So when Rwanda introduced its first national cervical cancer screening programme in 2011 to coincide with its vaccination campaign it chose another, simpler way.

Doctors and nurses would take a solution of acetic acid, a substance found in household vinegar. The solution allows abnormalities in the cervix that might be cancerous to appear white to the naked eye.

No samples or high-tech laboratories are needed. HIV-positive women can start this type of screening from the age of 30 while women without the virus have to wait until 35.

But the test is not without its limitations. South African guidelines caution that the test can produce false positives. In a 2015 study conducted among 300 women in an Indian hospital and published in The Journal of Mid-Life Health found that this method was 87% accurate compared to Pap smear, which was slightly more accurate at 93%.

In 2005, six African countries including Malawi, Tanzania and Nigeria began a four-year pilot of the technique to see how it would work among large groups of women. In total, almost 20 000 women were examined using the simple, vinegar-like solution. Researchers found that without having to wait for lab results to come back, about six out of 10 women who showed signs of lesions or other possibly pre-cancerous abnormalities were able to get treatment within a week. Delays in the other 40% of women were mostly due to a lack of working equipment or needing their partners to consent to treatment. Almost all of those who underwent these procedures would recommend them to other women, a 2012 WHO report shows.

On the heels of the results, several countries planned to scale up this form of testing.

Meanwhile, the closest health centre in Bugesera near the Rwandan-Burundi still doesn’t do cervical cancer screening, says community health worker Odette Mukarumongi. Instead, she tells girls and women that if they experience any symptoms of cervical cancer, like pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding, they should go to the health centre for a check-up.

Rwanda goes where the Pap smear has never gone before. (Shonagh Rae Heart)

Merck’s HPV vaccine donation programme ended in 2014. But just as Feinberg had hoped, the Gavi Alliance announced it would co-finance Rwanda’s HPV programme. Rwanda would chip in US$.20 (R3) per dose of the jab and the internal donor would cover the remaining $4.50 (R63) of the cost.

But Gavi’s money is unlikely to last forever. The donor aims to support the world’s poorest nations to vaccinate their populations so countries become ineligible for funding as they become richer and once their gross national income per capita exceeds US$1 580 for a period of three years. Once countries hit this threshold, Gavi begins to phase out financial backing.

Eventually, Rwanda will have to fully finance its HPV vaccine campaigns on its own.

Felix Sayinzoga from the Rwandan ministry of health’s maternal, child and community health division admits he’s worried: “The HPV vaccine is very expensive.”

He says: “What we are doing annually is looking at how we can plan for the next three years. We need to invest in the life of our people.”

— Additional reporting Laura Lopez Gonzalez

This is an edited version of an article first published by Wellcome on mosaicscience.com and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence. Sign up to the newsletter at http://bit.ly/2DRzmEu Wellcome, the publisher of Mosaic, is funding a number of projects related to HPV, in places including the UK, Tanzania and the Gambia.