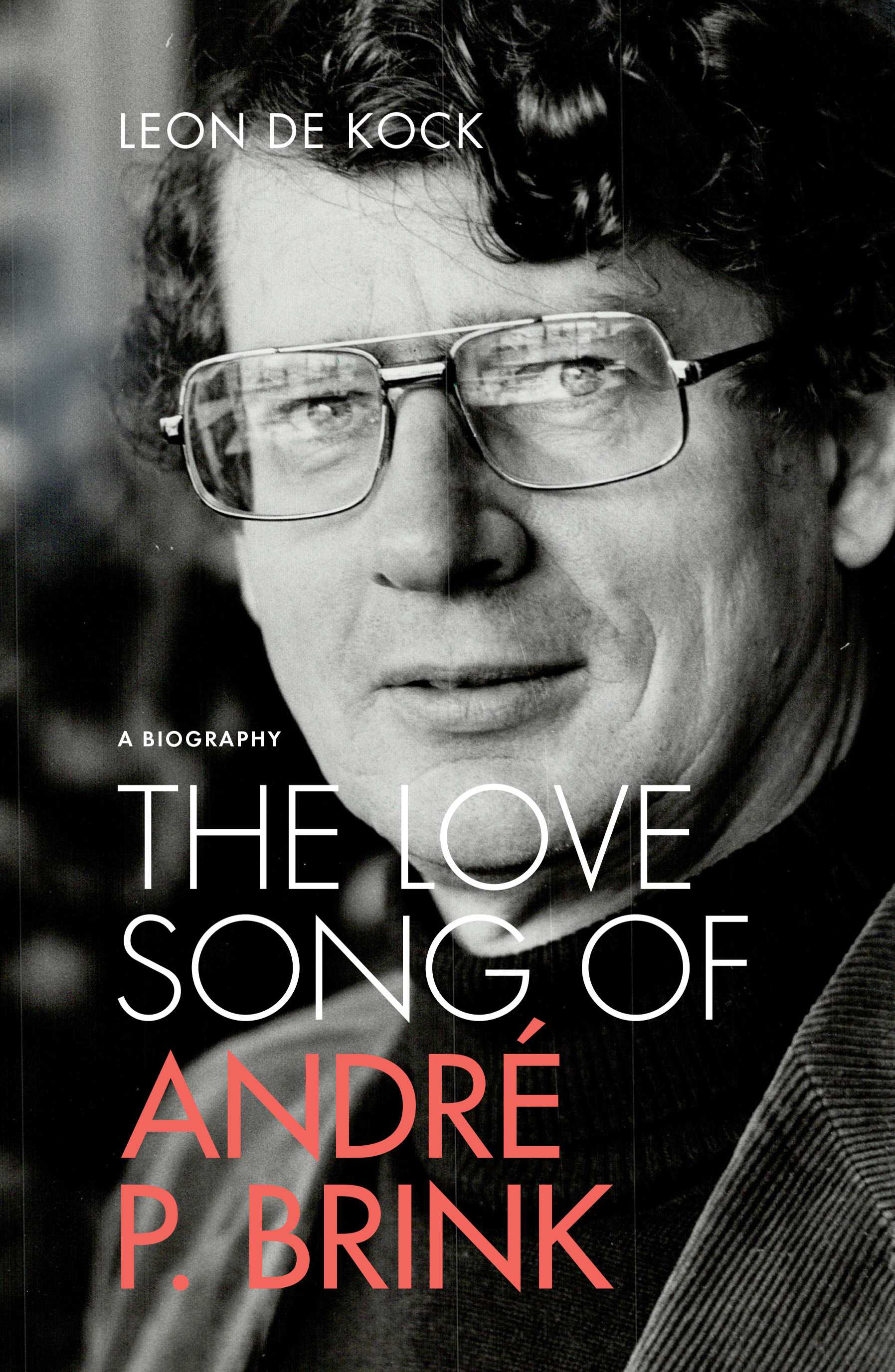

Graphomania: André Brink wrote personal journals throughout his life. (Louise Gubb/Corbis/Getty Images)

THE LOVE SONG OF ANDRÉ P BRINK by Leon de Kock (Jonathan Ball)

Leon de Kock’s biography of André Brink appears in both English and Afrikaans, as did the major works of the Afrikaner author. In English, the biography is titled after TS Eliot’s poem, The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock, and the piece of that poem that appears at the start of De Kock’s book is appropriate enough: “There will be time …/ … for a hundred indecisions,/ And for a hundred visions and revisions …”

But, otherwise, Prufrock and Brink are a distinct mismatch. The timid Prufrock, after all, wonders: “Do I dare to eat a peach?” He is overwhelmed by the possibilities of sensual experience, whereas Brink spent a huge portion of his life in pursuit of sex and sensuality.

Prufrock admits: “I have measured out my life in coffee spoons” — the smallest implement in the early 20th-century cutlery drawer. Brink, on the other hand, measured out his life in novel upon novel, some of them rather large, plus vast amounts of non-fiction writing (important critical works such as Aspekte van die Nuwe Prosa as well as thousands of reviews and columns), volume after volume of private diaries, and a long, long stream of lovers.

Perhaps the Afrikaans title of the biography sets the tone better. It is André P Brink en die Spel van die Liefde, in which spel is “play” as well as “performance”. Certainly, it is clear from the biography that Brink needed to perform love, or to turn sexual lust into a performance of love. Driven by desire that seems to have been largely sexual, he was also driven to transform his lust into love by idealising these women, elevating his desire into something more noble by conceiving of them in the most romantic of terms. When the transformation didn’t work, he complained to himself, usually after sex, that he felt “uninvolved”.

De Kock had access to Brink’s personal journals, which he wrote, voluminously, in parallel with his other writings. They were generative of his other works, surely, but also an ongoing accounting to himself of his tumultuous feelings and a way of processing them. De Kock says the journals, placed together, would easily fill a decent-sized shelf — millions of words over and above the millions he published.

Coming out of a fairly conservative Afrikaans background, at a time when apartheid, white supremacy and Afrikaner nationalism were in their pomp, Brink underwent a swift makeover once he was exposed to European currents of thought such as existentialism. He also began to see apartheid South Africa from the outside, and it horrified him.

He filtered these perceptions into his writing, which grew steadily more radical and dissident: first the sexual radicalism of works such as Lobola vir die Lewe (1962) and Orgie (1965), which shocked the Calvinist establishment, then the political radicalism of works such as Looking on Darkness (1973) and A Dry White Season (1979), which exposed the evils of the white National Party (NP) government and its apparatus of repression.

The sexual comes first. Brink saw existential freedom in sexual terms. Looking on Darkness, as Kennis van die Aand, was the first Afrikaans novel to be banned by the South African censors. The story of a love affair across racial lines, it was radical in that simply positing and describing in depth such a relationship was subversive of NP policy, such as the Immorality Act, the sexual and matrimonial version of the state’s desire to keep white and black people apart at all costs.

Works that followed deepened the implications of what it meant for the dividing lines of apartheid to be broached. An Instant in the Wind (1975) explored the historical resonances of co-operation and understanding between black and white; A Dry White Season retold the story of Steve Biko’s death by telling of a white man’s quest for the truth. Here, Brink’s work was at its most radical. Afrikaans author Marita van der Vyver speaks of how the sexual narrative of Looking on Darkness was an eye-opener for someone who grew up in repressed Calvinist Afrikanerdom, and I am assuredly not the only white South African who found in A Dry White Season the spark of a political education.

Brink showed immense courage in his political dissidence, enduring security police harassment and general opprobrium from the Afrikaner establishment, while refusing to go into exile as did his close friend Breyten Breytenbach. Yet his sense of what it meant to fight for freedom had roots in his quest for existential freedom, which for him was located in the erotic. De Kock tags him as a kind of Don Quixote, but he was just as much a Don Juan.

At the same time, Brink was always torn between a conservative understanding of the meaning of love and sex (as in marriage and fatherhood) and his freedom to follow the scent of his lusts. The vacillation led to much pain for him and others. The journals show a man, as De Kock puts it, who “seemed so swiftly to swing from guilt and self-flagellation to joy and erotic affirmation” — and back again. The guilt was, perhaps, an essential part of the package.

Brink married young, and then his formative affair with poet Ingrid Jonker shattered that marriage. Yet his tortured relationship with Jonker, who died by suicide in 1965, did not put him off either his later attempts at marriage and a stable family life or his repeated, almost cyclic, pursuit of sexual liaisons outside of marriage.

His marriage to Alta Miller ended because of his many affairs. (Getty Images/ Bettmann)

He was married five times and each time, except for the last one, the marriage was compromised and finally destroyed by his affairs. He kept pursuing his lust objects relentlessly, romanticising them all the while, even as he bounced traumatically between wives and mistresses (“a hundred indecisions”). And he wrote it all down (“a hundred visions and revisions”) as it happened.

The graphomania and the erotomania went hand in hand. This is made clear by an episode when he was still at school. At 17, he developed a passion for a girl pen pal who was a mere 12. Enflamed by one small, black-and-white photo of his correspondent, and more by his own letters to her than hers to him, he blew up a cool, arm’s-length interaction, with almost no personal contact, into a vast but substanceless romantic vision.

That may be expected, perhaps, of an over-excited 17-year-old, but Brink basically kept on doing this kind of thing for the rest of his life. It was only towards the end, when he was 70, that he achieved a marriage that stabilised him. This marriage, to the Polish-born Karina Szczurek, who was 27 when they met, is presented by De Kock as a telos in Brink’s life — he finally “got lucky”.

Such a conclusion makes a warm and fuzzy ending for the biography and Brink’s life, but it feels too much like an endorsement of conservative mores, as if to say that Szczurek was the woman who finally tamed him, who gave him the socially acceptable role he had been really questing for all along.

Perhaps this is a question about social roles, about public personae (which include that of the married man and father) versus a private, inner self that is essentially subversive of such social roles. It’s hard to conclude that Brink reconciled the two, or integrated the inner and the outer.

It’s notable that, throughout these long periods of inner romantic and sexual turmoil, Brink maintained a cool, courtly public exterior. To those who encountered him in a relatively superficial way, he seemed relaxed, confident and gracious. Were these different sides of him in conflict, or did they, in some more complex way, support and enable each other?

Whatever the case, De Kock’s biography is a compelling read in its own right, judiciously balancing Brink’s vivid inner life with his public roles, the life of the writer, the public intellectual and leading academic.

One might have wished for more detail on his literary work, but that has been done elsewhere, and De Kock is very good on the way the life and the work fed each other.

Above all, The Love Song of André P Brink is a compelling and intimate portrait of a compelling figure and his complicated intimacies.