From Binyavanga, Brian Kamanzi learnt the importance about different kinds of writing and that it always involved confronting yourself.

“Never, ever smoke this will kill you. If you even step on it your lungs will turn black” he said with a wry smile breathing deeply setting aglow his cigarette for its final few moments of purpose. After tossing it to the ground he turned his gaze sharply towards me, standing no taller than his knee and nudged me as we walked towards his sister Ciru’s door.

We knew him as “Ken” in those days, and on that morning we walked through the University of Transkei apartment compound UNIWES where our family lived. Uncle Henry and my father Kamanzi, after a long odyssey across several places in East and Southern Africa had found a home in Fort Gale, in what was then Umtata. After gaining some stability their families soon received their nephew, Ken and nieces, Ciru and Lynda. My earliest memories of family, unreliable and scattered as they may be, have this trio entangled in a montage of laughter, debate, disagreement, love and storytelling.

We lived in a world, which many in the country may not know existed, wrapped around the university, UNITRA, alongside people from the region, across South Africa, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Rwanda, Ghana, Bangladesh, India, Nepal and more.

Ken himself had arrived to study finance and marketing, and as the story goes, wasted no time in rebelling against any trajectory resembling safety and stability. The idea of the “Good Immigrant”, the middle class, the aspirant, the straight-and-narrow complaint postcolonial subject is something that Ken, later in life, wrote about often, with fierceness and great intimacy. In Umtata, now Mthatha, Ken would come to conflict often with his uncles in between their madcap efforts and adventures to make home and community in a valley surrounded by rolling hills.

The last time I saw him was around the fire at the naming ceremony of my niece Rosalia, daughter of my cousin Kirenga, the first born son of my late Uncle Henry. Ken — now Binyavanga — in a slurred speech, recovering from a recent stroke, vividly recounted Mthatha misadventures. Laughing from deep within his rounded belly he reminded his uncle, and the curious ears around them, of their attempts to slaughter a goat using ropes and pulleys which sought to replace the slender hands of brothers on our grandfather’s hill in Mutolere.

By the way, Ken also loved Nandos.

Binyavanga at war with the world, his family and himself headed to Cape Town to forge his own path. Now, far from from the weight and expectation of the “good immigrant” he found home and community on his own terms. The only ‘institutions’ Binyavanga tolerated were the homes for misfits, places of debate, contradiction and of course libations.

In what many still describe as the “Cape Colony” he sought Pan-Africa, not in the lecture halls and library’s of elite institutions but in the corridors, bars, and neighbourhoods frequented by fellow migrants and travellers. In spaces too undesirable to be considered “Afropolitan”, complex and alive with the possibility of a different way of being with each other. Places that trouble identity, boundary and border with food, music and also sometimes indifference and violence.

Binya, also loved Groove Lounge.

It would not be long before he found home in publications, comrades and family in Chimurenga, boss and soon interlocutors in major South African newspapers — after many years of struggle and outright rejection and depression. I was a teenager when he put together How to Write About Africa, I remember my father coming home from campus with an article in hand, pages neatly stapled in one corner. Very few words were exchanged about it but this was the first time I had heard of him referred to as a “writer”, a belated vindication for something he had known about himself long before the recognition that soon awaited him.

When I arrived in Cape Town to study Lynda spent a great deal of time trying to educate me. She then taught at the University of Stellenbosch and would periodically drag me to poetry readings and this and that book event. Poems and impassioned monologues about “revolution” — which a scrawny, stubborn engineering student dismissed as vague and obscure. Lynda reintroduced me to Binyavanga and invited me into a world of African literature that did not simply exist in pages bookstores but was alive all around me in ways I was initially not prepared to see.

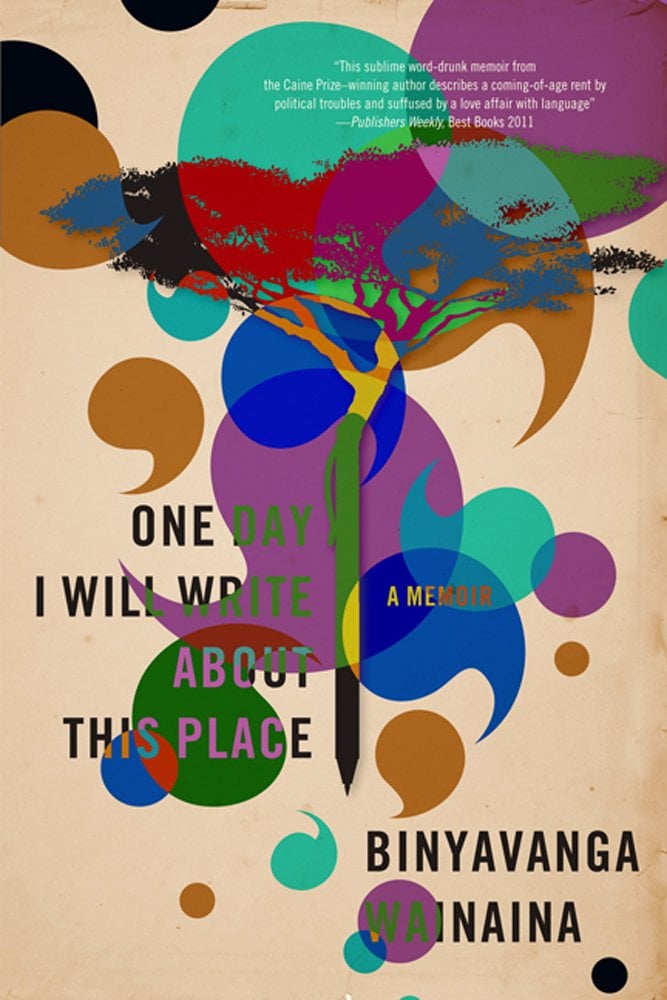

Binyavanga and I met, after very many years, at a launch of his book One Day I’ll Write about this Place at the Slave Church in Cape Town. We had ignited a friendship that had brought me to writing and start a journey to war with the world, my family and myself.

He encouraged me to write and compelled me not to just to talk but act. He help found organisations like Kwani? to support other African writers and ended every conversation we had over the years about his excited by a young person somewhere. I did not know him, as I wish I had, but already in the wake of his passing I am learning and tracing the road of life lived fully.

From Binyavanga I learnt the importance about different kinds of “writing” and that it always involved confronting yourself. From him I am still digesting that this too means visiting and revisiting moments in time, real and imagined, and allowing the messiness to bring change and not shy away from embarrassment of the many failings we often pretend do not exist or disguise through social media filters.

The story about Binyavanga is not the story about “The African Writer”, “Mavericks” and “Tortured souls”, it’s the story of the everyday, the banal, the absurd, the messy but also the tale of lifelong relationships, of pain, rejection and transformation. Writing about Ken. Writing about Binyavanga, as is writing about Africa, is about what is left off the page, what evades description forever immersed in a war between a harsh, and often bitter, reality and the persistent desire for a radical imagination to remake the world anew.