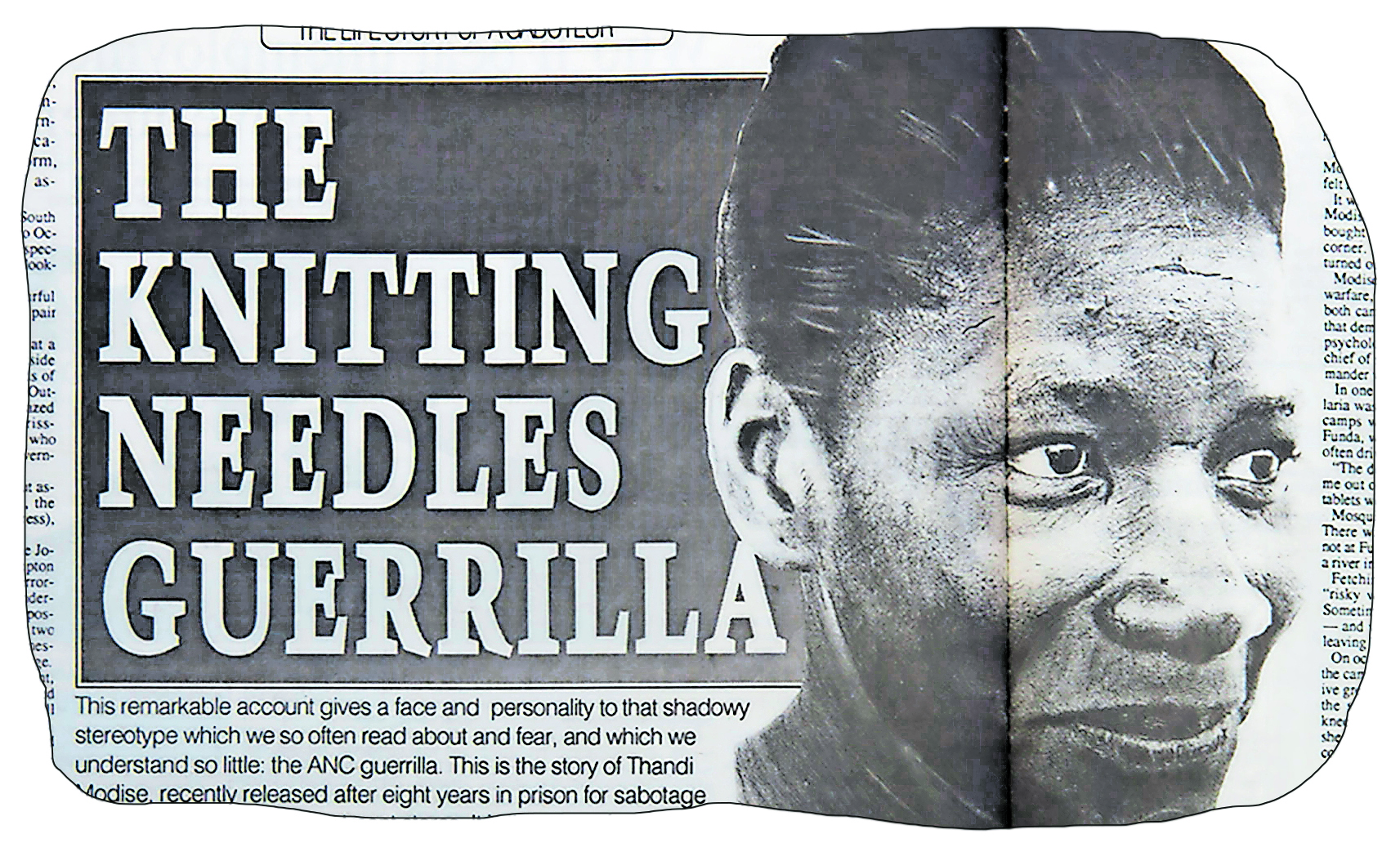

This is the story of Thandi Modise in the Weekly Mail March 23 to 30 1989 edition.

THE LIFE STORY OF A SABOTEUR

This remarkable account gives a face and personality to that shadowy stereotype which we so often read about and fear, and which we understand so little: the ANC guerrilla. This is the story of Thandi Modise, recently released after eight years in prison for sabotage at two Johannesburg department stores. It is the story of a tough and angry woman, whose rage goes back to her days at a small Cape school which had been set on fire by the pupils …

During her years underground, Thandi Modise bore no resemblance to the guerrilla of government propaganda — a sinister, camouflage-clad figure in combat uniform, lurking under cover with an AK-47 assault rifle at the ready. From January 1978, when she entered South Africa from Swaziland on a false passport, to October 1979, when she was arrested, the bespectacled ANC fighter went about her business looking as ordinary as possible.

She usually wore a two-piece suit or colourful slacks and carried a handbag from which a pair of knitting needles protruded. She formed part of the hustle and bustle at a busy police station. She was a passerby outside an South African Defence Force building. She was among hundreds of women shoppers in a city centre chain store. Outside the Krugersdorp power station, she gazed with curiosity at electric pylons and crisscrossing wires. She was one of the women who chatted with labourers tending gardens at government buildings, often inquiring about a job.

But in all these places, she was carrying out assignments for Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, the military wing of the ANC), reconnoitring potential targets.

After her arrest, Modise went on trial in the Johannesburg Regional Court and later in Kempton Park, where she was convicted under the Terrorism Act. She was originally charged with undergoing military training, recruiting for MK, possession of arms and explosives, and arson at two stores — OK Bazaars and Edgars in Johannesburg. She was acquitted on the recruiting charge.

Sentenced to a total of 16 years’ imprisonment, eight of which ran concurrently, she was released last November, just 24 hours short of her full eight years. She spoke freely to the Weekly Mail about the extraordinary life she led after she fled the country at the height of the 1976 student uprisings.

Modise, the youngest of six children, was born on Christmas Day 30 in the Vryburg township of Huhudi in the Northern Cape. At the time of her birth, her father, Frans Modise, was an ANC activist. The organisation was banned a year later.

Thandi recalls her father was an orator who spoke regularly on public platforms of the ANC. A stoker on the railways, he was among the first blacks earmarked for advancement as a driver. His chances, however, were thwarted by his commitment to politics. Although as a child she liked to copy her father, she said her scanty knowledge of her father’s activities had no direct bearing on her eventual decision to undergo military training.

In December 1974, Modise discovered that she was pregnant. The child – a daughter called Boingotlo — was born prematurely in early 1975, and given over to the care of Thandi’s mother. In March she returned to the classroom, and her schooling continued until mid-1976, when she – and thousands of other South African students – left school never to return.

It was not the contentious issue of Afrikaans imposed in 1976 as a medium of instruction in black schools that sparked her resistance to apartheid. Afrikaans, she said, was no problem in the Northern Cape among black children, who interacted freely with Afrikaans-speaking coloured pupils.

It was “unprovoked police harassment” on school premises that angered children, she said, resulting in the closure of her school, Barolong High School. The school, known as a hotbed of political activity, was later re-opened — but when she returned to class she found it had been set on fire. Modise claims she was harassed by the security forces, who detained her and other students on suspicion of arson. She was never charged.

With police allegedly refusing to heed students’ peaceful demonstrations against the presence of security forces, she said, pupils became more militant. Violence escalated, and many pupils took part when a policeman was set alight. “I saw him being burnt alive,” she said. “It was the incessant resistance of the oppressed masses that gave me the courage to resist apartheid violence, ” she said.

The students’ revolt coincided with the build-up to Bophuthatswana’s “independence”. Anger over the possible incorporation of her community into the “homeland” also contributed to her decision to flee the country.

The last straw, she said, was the day she alleges she was shot at by police. The bullets missed her, but she wanted to shoot back – and had no weapon. “My belief that my parents would not mind my decision to leave the country strengthened my courage,” she added.

Of the 10 schoolchildren to flee the country with Modise, six were from her school, two of them the youngest in the group — a 13-year-old boy and a girl of 15. There were six boys and four girls. Two of the girls in the group would later turn state’s evidence and testify against her at her trial.

Describing her flight, she says: “We started walking toward the Botswana border at 11pm in July 1976, and crossed into Botswana at sunrise. We had one aim — military training.”

ANC functionaries in Botswana offered both boys and girls a choice of going to school or military training, but girls were encouraged to continue their schooling.

Most of the girls responded to this encouragement, but Modise’s desire to handle a weapon and the challenge posed by military training led her to refuse the education option. She was the only girl in the group of 20 that subsequently left to train as guerrillas.

After the ANC had arranged travel documents for the recruits, they flew from Botswana to Tanzania via Zambia. The 20 were screened by the ANC in Dar-es-Salaam and became part of a larger group that was given elementary political education for a few months before they were taken to the Nova-Katenga camp — known as “Detachment June 16” – in Angola.

For the next year, Modise would move between the very modern Nov-Katenga and the more primitive Funda camps. At one time, there were fewer than 30 women of a total of 500 trainees. Woman guerrillas, she said, were a new phenomenon. “The male comrades respected us for having the courage to be soldiers. They did everything to make us feel their equals.” Perhaps because there were so few women, “everything was the same, except that men and women lived in separate barracks”.

Modise said the normal practice was for three or four women to share a room in the camps, although when she was the only woman at Funda, she occupied a room by herself.

They slept on inflatable mattresses, covered with colourful blankets. During the day, the airbags were arranged as lounge furniture. A stack of mattresses became a coffee table in the middle of the room. To add colour and freshness to the room, the women decorated it with greenery from a well kept garden at the entrance of Nova-Katenga camp.

Uniforms were the same: men and women wore camouflage trousers, shirts and caps and boots of black leather or green canvas. An alternative uniform was the greyish-green gear issued to urban guerrilla warfare trainees.

In both camps women and men were expected to follow the same training programme and to carry out the same chores. ”Women comrades experienced problems in the obstacle course. We tired quickly when scaling high walls, crawling under a low fence and crossing a wide river without a bridge,” Modise said. Also part of the training were olitical education, engineering, tactics, map-reading instruction in the use of weapons and explosions.

Everyone woke up before sunrise donned track suits or shorts and T-shirts and began the day with intensive physical training. These sessions were supervised by an instructor slogans and extolling revolutionary figureheads in the socialist world.

After exercise, the trainees washed, changed into uniforms and went to have breakfast in a huge dining hall — soup, bread baked at the camp, biscuits, and tea, coffee or cocoa.

Meals were followed by assembly outside.Rain or sun, the trainees stood in rows listened to international news read by men and women trainees assigned to the task and compiled by a special team from various sources including radio and newspaper reports. Once the news had been read, the soldiers were divided into sections and platoons to engage in day-to-day camp activities. Training was given in the use of an assortment offirearms, cannons androckets, mostly the Makarov pistol, the Scorpion machine-pistol and other communistarms, as well as the Israeli Uzi – the weapon Modise favoured.

South African arms – either abandoned or captured from South African soldiers -were donated to the ANC by the Angolan government and formed part of the weapons courses.

Military training was not only an outdoor activity. Soldiers spent the latter part of the day studying or consulting in the spacious library, which housed an assortment of books including works on the theories of Marx, Lenin and Engels as well as the ANC bulletin, Sechaba, and another ANC publication, Voice of Women.

Soccer matches were arranged. “My favourite soccer team was the ‘People’s Club’,” Modise said. “Others were Callies and Swallows, named after teams in South Africa.”

Films on warfare and revolution were screened for the trainees, while performances by a number of cultural groups formed part of entertainment. An avid fan of jazz and classical music, Modise sang soprano in a choir, which ANC president Oliver Tambo joined whenever he visited the camps. OR (Oliver Reginald), as Tambo is called by many, was given a rousing welcome on his arrival. “My choir welcomed him by singing his favourite song, Vukani mawethu (Arise, our people), which was popular in South Africa’s black schools when he worked as a teacher in the 1950s. Home-brewed choral music filled OR with nostalgia, making him an instant star chorister. Surprisingly, he sang also.”

Monthly parties, whether to mark birthdays or other events, became the norm. The trainees wore civilian clothes for these occasions issued to them from a store of new or used clothing donated to the camps and usually worn at weekends. They ranged from jeans and sandals to elegant fashions: “I still long for my soft cream two-piece suit made in Paris,” Modise said.

At these parties the “comrades” drank and danced to the strains of music played by local jazz and disco bands. On hand were Konyaki vodka and beer, as well as cake and cold drinks.

In both camps, rise was a staple. “We all craved pap,” she said, “but it was never on the menu.” There was, however, canned food from the Soviet Union and East Germany, sometimes game – buffalo or wild pig hunted by some of the trainees — and, at Funda, fresh vegetables grown at the camp.

Modise was occasionally invited to dinner at the Luanda residences of MK commander-in-chief Joe Modise and his adviser, Joe Slovo. Slovo was particularly good at preparing powdered eggs, and these became her favourite dish. One evening at Nova-Katenga, an unsuspecting Modise was among the soldiers who were served baboon meat, brought to the camp already skinned by the hunters. “After we had had supper and had finished custard and canned fruit, one or the hunters announced that the meat we had eaten was in fact baboon.”

Rather than being horrified at this discovery, Modise said she enjoyed the experience, as she felt it prepared the trainees to live off the land. It wasn’t the first unconventional food eaten by Modise. “In Dar-es-Salaam the male comrades bought what we thought was fish from the street corner. It was delicious. I asked for more.” It turned out to be python.

Modise was trained in urban and rural guerrilla warfare, specialising in explosives. She served in both camps as a political commissar, a position that demanded she plays the role of doctor, nurse, psychologist and social worker. She was also chief of supplies and assumed the duties of commander when the incumbent was absent. In one camp, she was the medical officer. Malaria was a common problem in Angola, and the camps were full of mosquitoes — particularly Funda, where people visiting the pit toilet were often driven out by mosquitoes. “ The devils bit me on the buttocks and forced me out of the toilet,” Modise said. Anti-malaria tablets were administered as a matter of course. Mosquitoes were not the only hazard at Funda. There was running water at Nova-Katenga, but not at Funda, where water had to be fetched from a river infested with crocodiles. Fetching water and doing the laundry were “risky without an AK at the ready,” she said.

Sometimes the trainees saw a crocodile surfacing – and would flee in terror. “One comrade fled, leaving behind her AK”, Modise said. On occasions like Women’s Day, the women in the camps wore special uniforms. One was an olive green jacket and a skin with a slit at the back; the second was a grey dress worn above the knee. The latter outfit was nearly discontinued, she said, as it incited “wild stares from the male comrades”. But both uniforms “gave us a feminine touch”, and the women liked to wear them. “We drilled in the short dresses on women’s occasions and we felt like women. The men whistled, but we ignored them.”

Modise had just completed a course in rural guerrilla warfare at Nova-Katenga when she was posted to another camp for advanced weapons training. She boarded a bus along with a number of Cubans on their to Luanda for a flight home and MK soldiers. “lt was a luxury bus donated by the GDR strictly for use by woman combatants,” she said. In fact, she was the only woman on the bus. Weapons were laid on a rack above the seats, and she took a seat towards the back of the bus. The trip proceeded slowly, as the bus was driving behind a bakkie carrying peasants. Suddenly she heard the sound of gunfire and the bus screeched to a halt. “l was frightened when I saw Cuban and MK soldiers in front grabbing weapons and scrambling for the single door.”

She snatched an AK rifle from the rack. “There were flashes of light outside caused by shooting. The weapons were obviously loaded with incendiary bullets.” It turned out to be a Unita attack. She leapt out of the window next to her seat. “I don’t remember how I landed. Training equips one to fall without hurting oneself. I fired rapidly in the direction of Savimbi’s men as I fell. “There were no survivors among the unarmed peasants,” she said. “I saw bodies scattered all around the bakkie. I saw blood — lots of it.” There was sometimes danger inside the camps as well.

In the same year in Angola, all 500 men and women at Novo-Katenga suffered severe food poisoning. Trainees believed South African agents were responsible. The main supper dish, she recalled, was fish, rice and vegetables. In their despair diners held their hands to their bellies, “vomiting and collapsing. Several were admitted to hospital and treated by Soviet, Cuban and doctors”.

At the beginning of 1978, Modise proceeded to Maputo for further training. She stayed in a private house near the Swaziland border which was attacked by South African security forces in the early 1980s. She learnt later during police interrogation in South Africa that she had been kept under surveillance by South African agents in Maputo. South African police, she said, showed pictures of herself taken during her short stay in Mozambique and kept in what they referred to as a “terror album”. A few days after her 19th birthday, using a passport with a false name, Modise crossed the Swaziland border into South Africa.

Thami Mkhwanazi, who has died in Atteridgeville, Pretoria, at the age of 75, was a journalist who was sentenced to seven years in jail under the Terrorism Act for conspiring to recruit people for the ANC and help smuggle them out of South Africa for military training. In 1980, he was sent to Robben Island where he spent the first three years of his sentence.