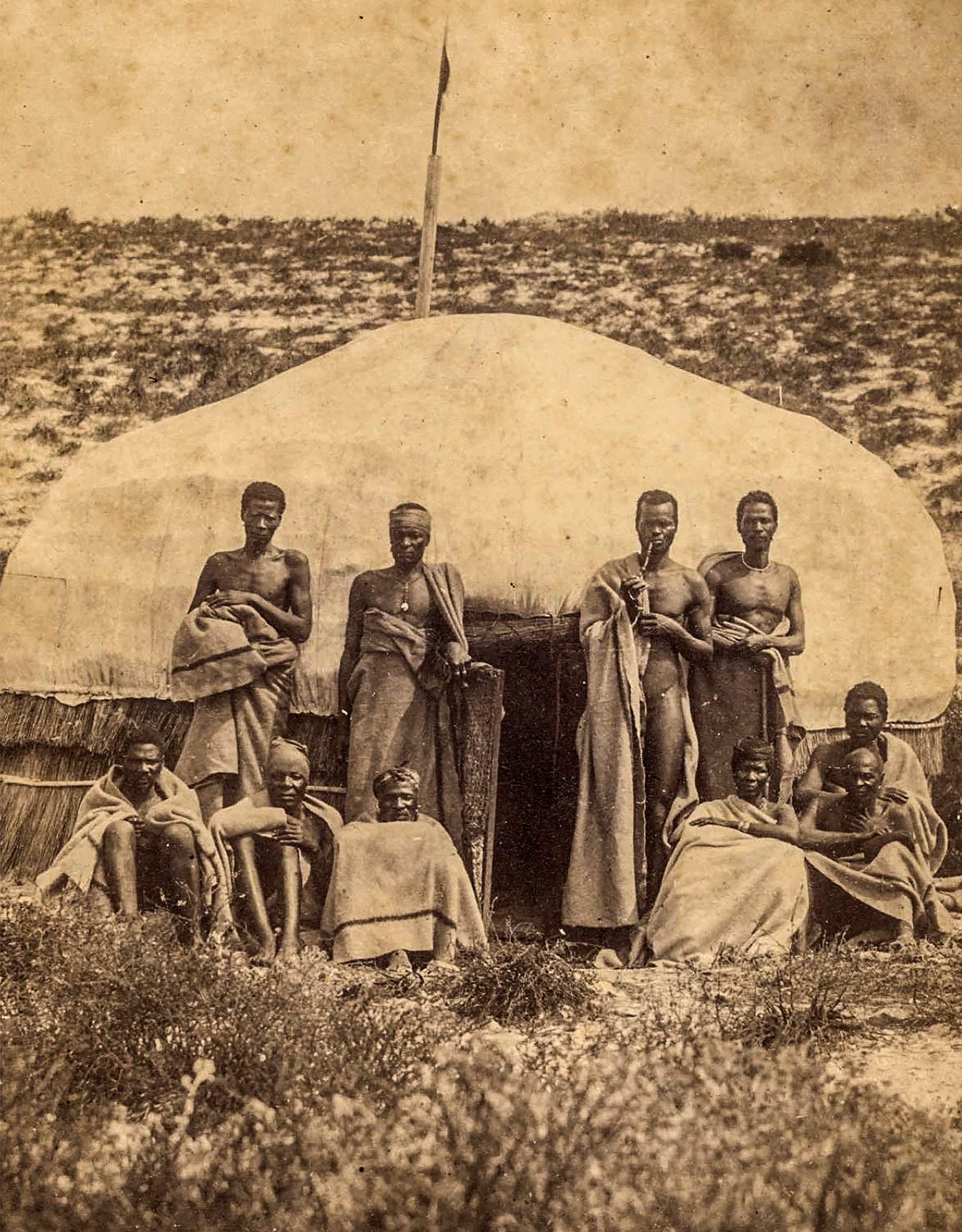

AmaTshatshu chief Maphasa (left) meets the British.

THE HOUSE OF TSHATSHU

by Anne Mager and Phiko Jeffrey Velelo (UCT Press, Juta and Co )

As one drives through Cradock, in the Eastern Cape, past Whittlesea, Cofimvaba, Cathcart and Tsomo down to the Great Kei River, signposts at the threshold of dusty tracks lead into the rural hinterland of the former Transkei and into the past. Bawana, Maphasa, Gungubele, The Gwatyu Great Place; these are names of chiefs and territories associated with their reign that hark back to a neglected and, until now, largely unacknowledged chapter of South African history.

They form the fulcrum of a powerful book called The House of Tshatshu: Power, Politics and Chiefs North-West of the Great Kei River c1818-2018. Written by University of Cape Town historian and professor Anne Mager and Phiko Jeffrey Velelo, an Anglican priest, agro-economist and the Tshatshu chief’s councillor, the book follows a complex and tragic trajectory of dispossession, displacement, deception and dreams of reclamation that persist today.

Meticulously researched over eight years, Mager scoured archives in Bhisho, Cape Town, Pretoria and London and, together with Velelo, extensively interviewed amaTshatshu descendants. Velelo’s input is crucial, reinforcing the imperatives of developing revised histories of this country, penned by South Africans with respect for and knowledge of identity politics.

The collaboration between Mager and Velelo entailed interrogating their own personal and divergent histories experienced in the Eastern Cape. Velelo is a direct descendant of amaTshatshu and belongs to a displaced progeny desperate to reclaim their heritage. Mager was raised on a farm in the Swart Kei, ironically named after the legendary Tshatshu chief Maphasa. Acknowledging the parallels, uneven power relations and biographical contradictions made for a raw and honest collaboration. Consequently, The House of Tshatshu does not read as an academic treatise of the tribal “other” conveyed through the gaze of the ethnographer or anthropologist. Rather, it resonates as an epic tragedy that holds potency and capital in the current volatile discourses about land reform.

The contemporary significance of The House of Tshatshu was brought home shortly before our May elections when a group of 2 000 farm dwellers from 88 farms in the terrain of Gwatyu protested outside the East London offices of the department of rural development and land reform. They are demanding security of tenure on this intractably beautiful land stretching 44 000 hectares across former West Thembuland. Their cause has been taken up by the Democratic Alliance, with an ultimatum being given to the department to transfer ownership to the farm dwellers or face litigation. This has sparked accusations and counter-accusations between the farm dwellers, who have formed a communal property association (CPA), and the traditional leadership and its descendants who believe the land is their own.

But the conflict cannot be fully understood without reading this tragic tome on the origins of Gwatyu and its connection to both ama-Tshatshu and farm dwellers. It serves as a prequel to and analysis of the failures that continue to plague land reform, where the challenges of redistribution, restitution and security of tenure include not only addressing past injustices and making farms productive, but also reclaiming identity.

Located north of the eastern Cape colonial boundary, in the 1820s Gwatyu was called Tambookie by the British colonialists, which is the San name for abaThembu groups who had themselves displaced the Khoisan occupying the area. One of the most powerful clans of Thembu was ama-Tshatshu, who were known as the fiercest of warriors. At the height of their power, amaTshatshu territory stretched across West Thembuland and included the present towns of Whittlesea, Cathcart and Komani. But with their defeat by British colonialists in the mid-19th century, the clan was decimated.

After the Tshatshu chief, Maphasa, was killed in 1952 — not in the battle of Imvani as stated by the colonialists — but by poisoning, Sir George Cathcart, the governor of the Cape at the time, issued the cruellest of decrees. He ordered the obliteration of amaTshatshu identity. The Tambookie location, which in 1894 became the Glen Grey District, was granted to colonial soldiers as a reward for participating in the frontier wars and the annihilation of the clan.

Members of amaTshatshu who refused to submit were rounded up, tortured, imprisoned or murdered, their people dispersed into exile in their own land. For example, Yiliswa, the regent queen of amaTshatshu, refused to obey colonial orders to move across the Indwe River. As punishment she was banished on a wagon, blindfolded, to the land ruled by her brother, Ndamase, in western Mpondoland.

An iniquitous pass system was introduced to control the influx of “natives” into lands now controlled by the colonialists. One of the pre-eminent Tshatshu chiefs, Maqoma, was arrested for not having a pass when he came back to survey his former lands. Together with the former regent, Fadana, he was sent to Robben Island from 1859 until 1869, when they were released on the understanding of “good behaviour”. Maqoma was re-arrested in 1871 and died on Robben Island in 1873. Fadana died there too.

Xhosa chiefs were sent to Robben Island during colonial rule.

The focus of the House of Tshatshu is primarily on the catastrophic consequences for a people whose identity has been obliterated and their struggle to regain dignity and empowerment through its restoration. The book also raises questions that confront contradictions within a postcolonial context, namely the role of chiefs and indigenous institutions disfigured by the colonial past only to be co-opted by the apartheid regime and their relationship with South Africa’s secular constitutional democracy.

For more than a century Gwatyu was the domain of colonialists and white farmers until 1982, when amaTshatshu traditional leaders regained official recognition from the apartheid regime. The chiefs were expected to be compliant civil servants, coerced by the illusion of hegemony over “independent” tribal homelands or bantustans. Gwatyu was incorporated into Transkei, under the rule of Kaiser Matanzima. With incorporation, most white farmers left Gwatyu, leaving behind generations of farm dwellers and labourers who continued to toil the soil, becoming farmers in their own right. Many of them bore no direct affiliation to the lineage of the Tshatshu, who had been forcefully dispersed a century ago.

The dawn of a nonracial, democratic South Africa — when ownership of the former homelands was transferred to the state — heralded hope for both the traditional leadership and the farm dwellers. The former lodged a land claim; the latter tried to gain title deeds to the farms so that they could restore land into a flourishing rural economy. The dreams of both claimants have been thwarted.

Today, Gwatyu is neglected, overcrowded and impoverished, its future paralysed by the state’s indifference, incompetency or — as many Gwatyu residents alleged — corruption. The competing ownership claims between amaTshatshu descendants, represented by Chief Mncedisi Gungubele (whose praise name is Jongolundi) and the Gwatyu CPA are allegedly being exploited by the department of rural development and land reform.

Chief Jongolundi wants the clan’s land back. (Anne Mager))

In 2016, Jongolundi’s wife, Nosizwe Gungubele, was killed in a car accident that left him severely crippled. Today, the Gwatyu Great Place, the chief’s homestead, is a forlorn monument to her memory. The CPA accuses allegedly corrupt officials in government and politically connected cadres of exploiting Jongolundi’s frailty to gain access to the land for allegedly nefarious purposes.

Descendants of amaTshatshu lineage make counter claims that the CPA is being exploited by outsiders and troublemakers for self-interest and who do not respect the traditional ties of amaTshatshu to Gwatyu. To date, the department of rural development and land reform has refused to register the CPA, and the results of a 2015 land audit requested by the CPA to determine to whom the land belongs have been mired in secrecy and controversy.

Dispossessed by colonialism and oppressed by apartheid, both sides of the Gwatyu divide now feel a profound sense of betrayal by the government they voted into power.

The House of Tshatshu provides a long-overdue acknowledgement of the history of a proud and persecuted people. It is also a lament and requiem for the dream of a promised land reduced to a land of empty promises.