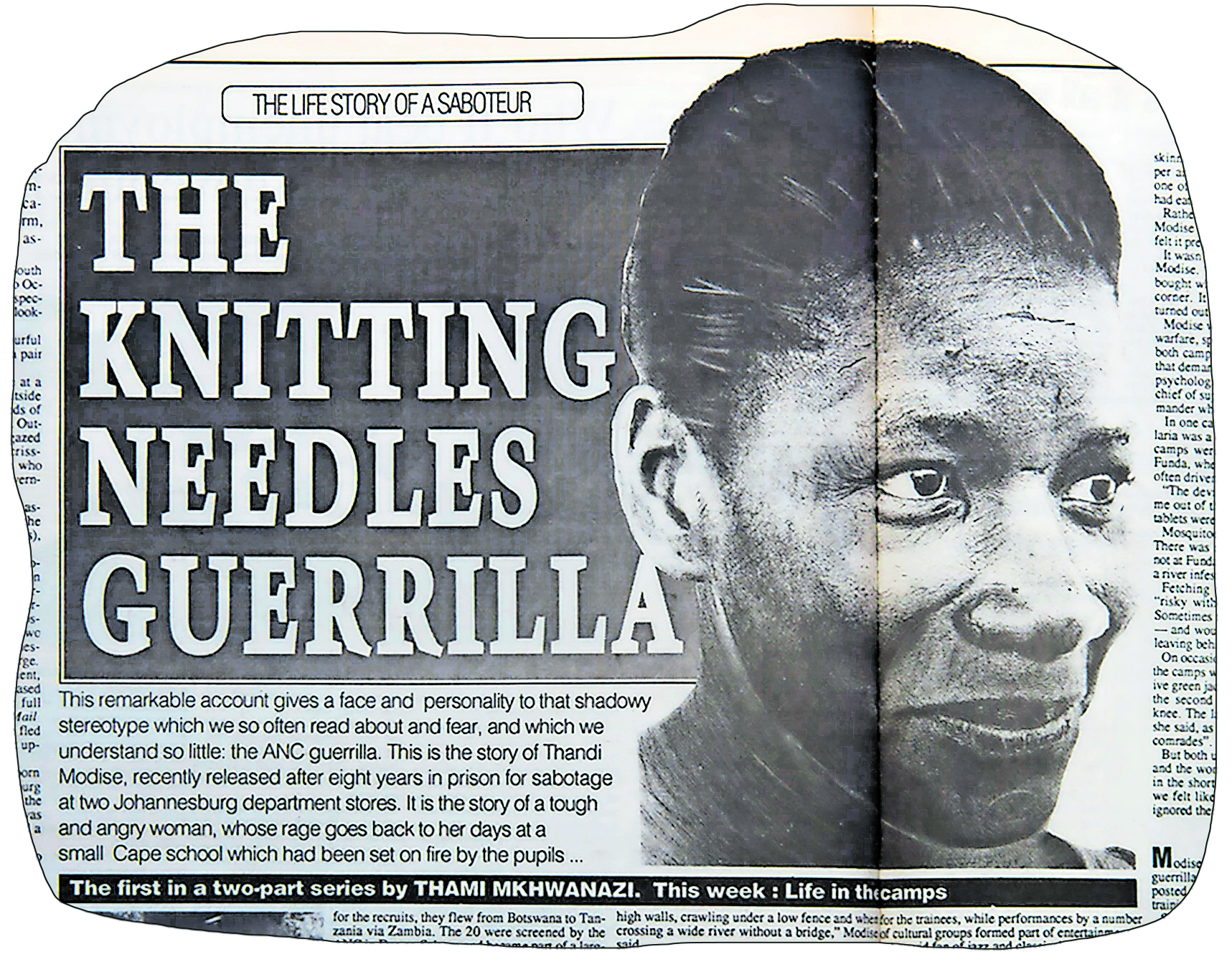

This is the story of Thandi Modise in the March 31 to April 6 1989 edition of the Weekly Mail. Here she embraces her daughter following her release from prison.

THE LIFE STORY OF A GUERRILLA: PART II

Fired with revolutionary fervour, woman guerrilla Thandi Modise slips back into South Africa … but it’s not long before police start following her. THAMI MKHWANAZI completes his two-part series on the life of schoolgirl who turned saboteur … and ended up behind bars. Read Part I: Thandi Modise, the knitting needles guerrilla.

Being a woman guerrilla back inside South Africa was no easy feat for Thandi Modise.

After her spell in ANC training camps in Angola. she found it difficult to adjust to civilian life.

Her life in the camps had been one of drill and marching. “Habits die hard. It was a hassle avoiding walking like a soldier in civilian Johannesburg. Often I stopped in the midst of the city hubbub to check whether I was walking like a civilian.

“Each time I look back, I had the creepy feeling someone was watching me.” Modise said she had also found it difficult not to call people “comrade” — the normal practice in the camps.

Her training also created problems in her love life, she said. “I found it strange when suitors said to me: ‘I love you; let’s get married and have children’.”

Marriage meant different things to guerrillas and civilians. In the camps people got married ”to deepen the spirit of comradeship in the interests of the revolution. The purpose of having and raising children was to build a post-apartheid nation.

Modise said her double life as a guerrilla had started when she crossed the Swaziland border under a false name.

“At the border post l gave my name as Zandile Simelane and had to speak siSwati. Later, when I moved to Diepkloof in Soweto, I became a Motswana by the name of Lorato, and in the last township where I was based, Eldorado Park, I operated as Miss Thandi Mentor.”

Modise was trained as a topographer, and her main job was to gather information about potential guerrilla targets. To accomplish this, she played various roles to enable her to observe strategic installations at close range.

In order to reconnoitre police stations, she complained to the policemen on duty about the behaviour of an unfaithful husband — knowing full well that this was outside the normal scope of police duties and that the matter would not be pursued.

“On one occasion, a group of policemen in the charge office laughed at me and advised me to marry a policeman,” she said.

In order to collect information about the Department of Home Affairs, she pretended to be a hysterical Swazi visitor to South Africa who had lost her passport and her money.

At the Krugersdorp prison, a tearful Modise searched for an imaginary missing relative, whom she claimed had been arrested.

Her instructions, she said, were to make ‘”absolutely sure no innocent lives were lost if an attack was carried out. The ANC was at war with the enemy, and not innocent people.”

Targets were “symbols of oppression” such as police stations and other government institutions enforcing apartheid. Symbols of economic power — for example, large firms — were also targets in certain circumstances, she said.

It was because of her instructions to avoid loss of life that she had decided to stop her surveillance of the prison in Krugersdorp, she said, commenting that it was “impossible to attack the prison without loss of innocent lives”,

Modise was later convicted of planting incendiary devices in OK Bazaars and Edgars stores in Johannesburg in March 1978.

Recalling the operation, she said: “It took me only a day to inspect the stores. I entered towards closing time and laid inflamers between clothes in men’s, women’s and children’s departments.”

Wearing a maternity dress (although she was not pregnant), and carrying a sling bag over her shoulder, Modise passed through a security — checkpoint at the Eloff street branch of the OK Bazaars. She was carrying — among other items — a dozen boxes of matches containing

miniature inflamers timed to ignite some time after the store had closed. (An inflamer is a home-made device made out of ordinary household products, and containing a ready-made, manufactured timer. It can be shaped to look like an innocuous object – a watch, or a box of matches. It does explode but is ignited.)

“The security man peeped into my bag as I passed.” she says,” and moments later I sighed with relief”

Once upstairs she moved around the various departments looking for a suitable spot. She eventually placed the matches in an assortment of clothing and quietly headed for the escalator. Some of the boxes were placed in pockets of jackets.

She quietly rejoined the throngs of late shoppers pouring out of the building. Once outside, she walked to a nearby park and waited – peeping at her watch occasionally. Eventually, she says, “I took a taxi to base (Diepkloof) and waited for the news.” But news did not come until 24 hours later: “I thought the powers-that-be deliberately delayed the news for political reasons.”

The following day, Modise repeated the exercise at the Edgars store, about a block away.

Giving evidence during subsequent arson charges against her, staff members Petrus van Jaarsveld of Edgars and HA Venter of OK Bazaars told the court they had stopped the fires from spreading after spotting smoke coming from jackets. Venter said he found matchboxes next to a cash till.

While based in Diepkloof at a house secured for her by the ANC, Modise went out often on reconnaissance operations and on her return home drew sketches of what she had observed.

She would then cross into Swaziland to pass on the drawings to the Umkhonto weSizwe regional command — she left and re-entered South Africa on numerous occasions over this period. The regional command in turn would assign guerrillas to carry out the final attack.

In Diepkloof, Modise — under the name of “Lorato” — cooked, cleaned the house and attended to her hostess’ three children. Contact with these youngsters made her long for contact with her own child.

Her work as a guerrilla did not permit her to visit her daughter, Boingotlo, who had been born before she fled the country. The child was in the care of her mother who still lived in Modise’s birthplace, Huhudi in the Northern Cape.

After almost a year in Diepkloof, Modise saw her hostess slip out of the house at the dead of night and tiptoe to a police van waiting in the street outside.

Before leaving the house, the woman had checked to see if Modise was asleep. “I followed her outside and saw her sitting in the van with its occupants,” she said.

The next morning she moved out without giving her hosts note, and began sharing a flat with friends in the “coloured” township of Eldorado Park.

The problems at her Diepkloof hideout compelled Modise to suspend her reconnaissance and devote her time to the formation of political cells.

As Thandi Mentor, she began her new task of political mobilisation through a network of cells in Eldorado, debating with cell members the contents of the ANC political programme, the Freedom Charter.

Discussions on the charter, she said, were informally conducted. “We would base our debates on news reports in newspapers, and on radio, television and other media,” she said.

The end of Modise’s career as a guerilla came in October 1979, when she was arrested by two Indian security policemen and a coloured policeman in Eldorado Park. She was taken to John Vorster Square.

“It was late afternoon. I was busy preparing supper for family with whom I lived in the flat when I heard a knock at the door.”

Police told the court later that they had received a tipoff. The policemen searched her flat and confiscated a number of books, including one by South African Communist Party chief Joe Slovo. They also took away two bottles of potassium permanganate which later turned up in court as exhibits.

During her five-month interrogation, Modise said police had taken her to point out possible targets she had placed under surveillance. These included the OK Bazaars and Edgars stores.

The court heard during her trial that a group of white security policemen had taken her to a small hill in Eldorado Park, where they had allegedly forced her to dig a hole in search of an arms cache, and assaulted her.

She said she had known there were no weapons buried on the hill. “I was forced to dig, apparently as a punishment, when the police found the ground was undisturbed,” she said.

In May 1980, she appeared in the Johannesburg regional court on charges of undergoing military training; recruiting for Umkhonto weSizwe; possessing arms and explosives; and the arson attacks on the two stores.

In “a trial within a trial” aimed at establishing the admissibility of a confession made in detention, Modise said the police had abused her in various ways. She told the court that while she was being interrogated, black security policemen had escort her to the toilet and watched her relieve herself.

The state denied these allegations, and Sergeant Anita Hester Meyer testified that she was

responsible for escorting Modise to the toilet throughout the latter’s stay at John Vorster.

Modise also alleged that one of her interrogators, a Warrant Officer Jordaan, had stripped down to his underpants in front of her during interrogation. ”There were only the two of us in the interrogation room. I was pregnant and felt intimidated,” she said.

ln an attempt to show the court that she had signed a confession under duress, she mentioned a scar she alleged she had seen on Jordaan’s pelvis. She said Jordaan had boasted that the scar was the result of a wound sustained during a clash with Swapo guerrillas.

Jordaan denied the allegations, although he did say he had a pelvic scar which bad been left by an appendix operation.

Modise also told the court that she was struck with fists in an interrogation room called the “waarheid kamer” (truth room). These allegations were also denied by the police, and the magistrate ruled that her statement was admissible as evidence.

On February 15 1980, she gave birth to a daughter, Mandisa, in the Johannesburg Hospital. “Police told the hospital staff I was a Swazi princess,” she said, adding that the nurses and doctors had expressed surprise that a “princess” bad not brought clothes for her newborn baby nor a gown for herself.

She said the police had set about arranging for the adoption of the child. She was allegedly taken to welfare officers, who explained the advantages of having the child adopted. However, she had refused to sign the necessary papers.

“After Mandisa was born, my mother took her home,” she said.

Modise was released in November last year, one day before the official expiry of her prison term, which she served in Pretoria Central Prison and women’s prisons in Kroonstad and Klerksdorp.

While inside, she completed a B.Comm degree, and now plans to study law. But she is still paying for her years as a guerrilla. She says Bophuthatswana police harass her whenever she visits her two children, who now live with her mother in Dryharts village, in the Bophuthatswana region of Taung.

The state’s case against Thandi Modise

Thandi Modise faced three charges under the Terrorism Act, one under the Sabotage Act and another of attempted arson or malicious damage to property. The state alleged that between 1976 and 1978, Modise:

- Underwent military training with the ANC’s military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe and brought weapons into South Africa.

- Plotted with her co-accused, Cowie Moses Nkosi and Slim Aaron Mogale, to bring about a breakdown of law and order.

- Plotted with both men to commit arson at stores in Johannesburg.

- Propagated the aims and objectives of the banned ANC

- Reconnoitred police stations and West Rand Administration Board offices in Krugersdorp with the intention of carrying out sabotage.

- Was found in possession of a machine-gun, pistol, ammunition, TNT and calcium chloride explosives.

- Recruited for the ANC

The three accused first appeared in the Johannesburg Magistrate’s Court in May 1980. The trial was later transferred to Kempton Park. Convicted on three charges under the Terrorism Act, Modise was sentenced on November 7 1980 to a total of 16 years imprisonment, eight of which were to run concurrently.

Under cross-examination, security policeman Captain Seth Sols said when he and other policemen arrested Modise in an Eldorado Park house on October 31 1979, they found a Scorpion machine-pistol, a Bophuthatswana passport and a Swaziland passport hidden under the sofa. The police, he said, also found a bottle which contained chemical explosives and TNT in a tap near the toilet.

Eleven empty medicine capsules were also found under a clothing case. The state alleged the capsules had contained explosives which were used in the arson attack on the OK Bazaars. Captain Sols told the court he and his two colleagues had raided the house after receiving a telegram informing him about a woman who had received terrorist training outside South Africa.

During the trial, various police witnesses responded to Modise’s allegations that she was ill-treated while in detention. Lieutenant Deon Greyling told the court that on November 3 1979, he and two other officers took Modise to a hill in Eldorado Park to find something Modise had hidden there.

“At the spot we dug the earth out with our hands but found nothing,” he said.

Greyling said one of the policemen got angry and asked Modise to do the digging herself. When she also found nothing, he said, they all returned to John Vorster Square.

He denied Modise’s allegation that she had been assaulted.

Denying Modise’s allegations that she was assaulted in an interrogation room called the waarheid kamer, Warrant Officer Petrus Jordaan said he had never heard of a room at John Vorster Square being referred to in this way.

Thami Mkhwanazi, died in Atteridgeville, Pretoria, at the age of 75. He was a journalist who was sentenced to seven years in jail under the Terrorism Act for conspiring to recruit people for the ANC and help smuggle them out of South Africa for military training. In 1980, he was sent to Robben Island where he spent the first three years of his sentence.

This article was originally published in the March 31 to April 1989 edition of the Weekly Mail.