Omen: The Knysna fires of 2017. (Deon Raath/Rapport/Gallo Images)

Mega fires, such as those that raged through the Knysna area in 2017, could become more frequent, because temperatures and the number of high and extreme fire-danger days have risen as a result of climate change, according to a new report.

The report, commissioned by Santam, provides recommendations to local authorities, government and the insurance sector in a bid to prevent similar wildfires. Its findings have also brought home the growing threat that climate change poses for the insurance industry.

It also comes as the Reserve Bank, which has become the country’s insurance sector regulator under the prudential authority, flagged the financial stability implications of climate change for South African insurance companies.

“The effect of climate change on domestic insurers has been observed as extreme weather patterns that have increased the potential for liability claims, costing both insurers and clients more,” the Reserve Bank said in its latest financial stability review. It pointed to the Knysna fires and heavy floods in Durban — the former occuring in October 2017 and the latter in April this year — as examples of insurance exposures in the face of climate change.

Although the Reserve Bank said it did not appear there were imminent risks to the financial stability of the local insurance sector, “developments will be continually monitored”.

The Knysna fires cost the insurance industry about R2-billion in 2017 and have been described as one of the worst catastrophes in the country’s insurance history.

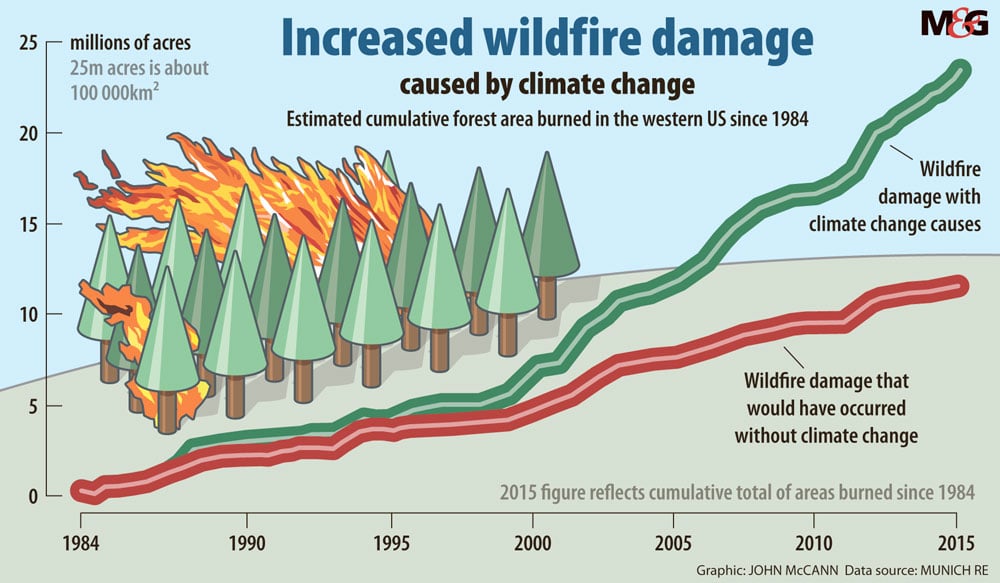

South Africa is not alone. Globally, such events are increasing in severity and losses.

According to Munich RE, one of the world’s largest reinsurers (companies that provide financial cover for insurance firms), wildfires in California in 2017 and 2018 reached unprecedented levels, with losses hitting $15-billion and $18-billion, respectively.

Santam’s chief underwriting officer, John Melville, said 2017 represented the insurer’s worst catastrophe experience by roughly two and a half times anything seen in the company’s 100-year history.

At the time Santam reported that it had paid out R823-million in claims as a result of the fires.

Santam’s reinsurance provided sufficient cover, although it “did get massive premium hikes the next year”, said Melville. Nevertheless, the company can still get reinsurance and provide insurance products.

But what the report revealed and what may be behind the prudential authority’s concerns, Melville said, is the worry that climate risk is left to “play out in an uncontrolled way over time”. This could see reinsurers “massively” restrict the cover they provide or make it so expensive that insurance becomes unaffordable. He said that this could lead to a “shrinking proportion of risk that is covered” and increased reliance on the state when things go wrong.

He argued thatto keep the insurance system viable, everyone had to work together to strengthen resilience and reduce the effects of disastrous climatic events.

The severe drought in the Western Cape between 2015 and 2017 was found to have been made three times more likely as a result of human activities, according to a paper, titled Anthropogenic Influence on the Drivers of the Western Cape Drought 2015–2017, written by a team of researchers. They also found that this trend will persist as global warming continues.

These issues are already affecting what kinds of insurance products are on offer — such as drought insurance for crops. Melville said Santam has reduced the amount of drought insurance itprovides and has withdrawn from certain parts of the country.

In other countries, such as the United States, government provides explicit subsidies for drought insurance, because it so expensive and it is viewed as a food security issue.

“What is quite helpful is when those schemes build in some kind of risk mitigation as a condition of the insurance,” Melville said —for instance, tying the subsidy to environmentally responsible farming and land management methods.

Despite the real danger climate change poses to their business, insurers may find it difficult to begin pricing for it.

A company that wants to price in climate risk faces a “first mover disadvantage”, according to Nick Simpson, a postdoctoral fellow with the Global Risk Governance programme at the University of Cape Town. A competitor that does not price in this risk could easily undercut a company trying to do the noble thing by providing cheaper premiums, he pointed out. Competition law also prevents firms from acting on this issue in concert, because it could be seen as collusion.

At a general industry level it is “almost impossible” for a company to act on its own, Simpson said. The problem may require the insurance regulator to introduce some form of control or reporting standard, he said, to move both insurers and their clients in the right direction.

He said that although only about 17% of South Africans are insured, this equates to about $42-billion — “a large chunk of our economy”.

But taking the view that this is merely about “saving the rich” is simplistic, he argued, because the potential knock-on effects need to be considered. For example, climate change is a major threat to coastal regions, home to some of the most valuable properties, and threatens the value of these properties. This, in turn, has implications for municipal levies and taxes, which serve as major mechanisms for cross-subsidising local services.

The effect that climate risk is having on what types of products insurers offer is in its “embryonic phase”, said Simpson, “but it’s nowhere near where I think it’s going to get to”.

(John McCan/M&G)

(John McCan/M&G)

It is difficult to determine the extent to which climate events are affecting local insurance premiums, said Simpson. Insurers play “a balancing act” between responding to local shocks and the price of reinsurance on the global market, which is influenced by events in regions such as Florida, which faces destructive storms during its hurricane season.

But what is certain, Simpson said, is that the model used to calculate risk has to change. Until now the industry has calculated risk on

historical loss data. But this backward- looking data comes from a “Holocene world”, he argued, and is very likely to lead to “maladapted decisions” for a world with a highly variable climate.

Knysna report says climate change is extending fire season

This week, Santam, the country’s largest general insurer, released are port into the Knysna fires of 2017, produced bythe Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, the Research Alliance for Disaster and Risk Reduction and the Fire Engineering Research Unit at Stellenbosch University.

In her foreword to the report, Santam chief executive Lize Lambrechts stressed that understanding and mitigating the risks posed by volatile climate conditions is crucial for the insurance industry and all spheres of government.

The report found that climate change is extending the fire season in Southern Africa, as a result of rising temperatures and the increasing number of high and extreme fire-danger days.

Although there is not yet a clear upwards trend in fire frequencies locally or globally, the report said: “There is evidence that fires are becoming more difficult or impossible to control.”

The severity of the Knysna fires was caused bya “perfect storm” of meteorological, biophysical and institutional factors, the report found. These included a prolonged drought and an abundant fuel load created by vegetation (including plantations) not being properly managed on both private and municipal land, as well as weaknesses in authorities’ incident management and response capabilities.

Along with recommendations for the government and the public, the report outlined ways for the insurance sector to help local authorities mitigate risks. These included helping to build the capacity of municipal fire-fighting services and fire-protection associations.

It also recommended that, as a way to help reduce fuel loads, the insurers require policyholders to help reduce flammable materials in fire-ignition zones around their homes. And the report identified the need for more affordable products for the “missing middle” —people who were uninsured or underinsured.

“A key challenge lies in knowing how to support these households, [that]currently fall through gaps in existing social safety nets,” the report said