Decolonising young minds: Historian and educator Nomalanga Mkhize has written and published a childrens book that positions Africa as important and central to history. (Paul Botes)

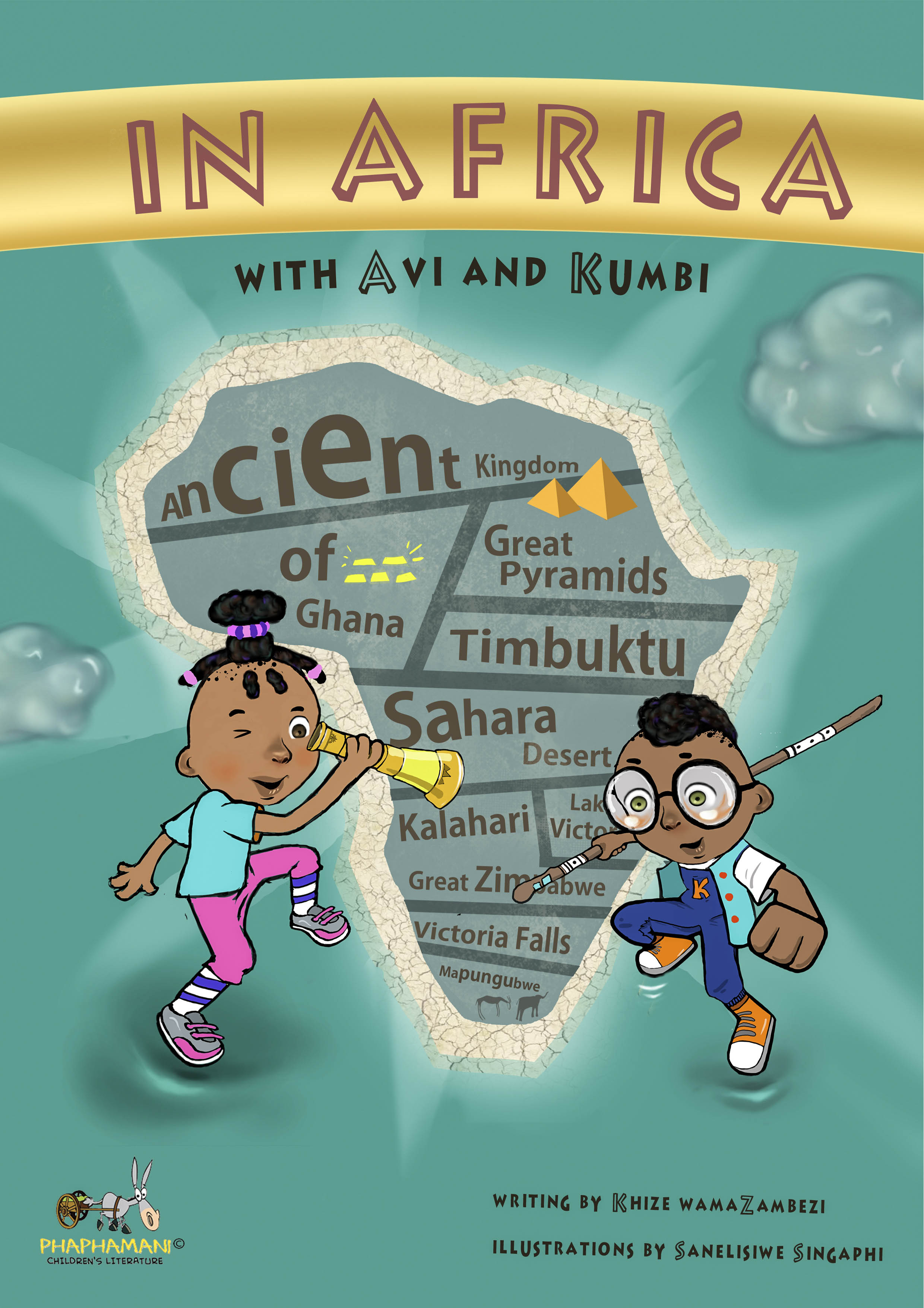

‘Initially, it was gonna be just trivia. Like, ‘What is the highest mountain?’ Volcanoes, you know, just fun,” says historian and educationist Nomalanga Mkhize about the evolution of a new children’s book, In Africa with Avi and Kumbi, published through the imprint Phaphamani Children’s Literature.

“Since we didn’t have much money, we decided to provide a standard account of an overview of African history that gives people in South Africa — for their kids — a coherent view of how the story of Africa should be told because that’s what’s missing. It’s the coherence. Like, where do we all fit in together on this continent?”

An overview, yes, but there is nothing standard about In Africa with Avi and Kumbi, which covers the development of African societies while paying careful attention to the effect of the illustrations and the look and feel of its pages.

“Focusing on trying to produce a high-quality illustration book took a lot out of the artists,” says Mkhize. “Remember, these are two artists from Motherwell and why we needed a lot of funding was to make sure that these artists are not undervalued. Even though we own the company [Phaphamani Children’s Literature] together, they needed to eat because they are self-employed. So getting it as high quality as possible is what then made it possible to find a distributor.”

Before publishing the book, Mkhize, who uses the pen name Khize wamaZambezi, and her illustration and design team consisting of Sanelisiwe Singaphi and Bulelani Booi, had been building their in-house capacity for years, working with isiZulu newspaper Eyethu on a comic that covered everything from science to art. They also supplied content to Isigimidi samaXhosa, a historic isiXhosa newspaper that was briefly revived by editor Unathi Kondile.

“It was from analysing what education really means,” says Mkhize of the journey to publishing. “It is not just something that happens in a classroom. Education is a social culture. So I said to my friends: ‘What we really need to do is contribute to the social culture of education.’ Through that social culture you can create a different image of education. So with the isiZulu language comic we were doing really well because we were producing very high-quality material for a publication that reaches a lot of people.”

As a parent herself, it began to dawn on Mkhize just how much of a monopoly exists around the culture that children consume, hence the need to do something that could appeal to different language groups.

“My child is, like, five or six,” she says. “I don’t have a problem with her watching Disney, I have a problem when that is the only stuff that is dominant on TV and it is reinforced in the way literature for kids looks. So they build a universe of Western symbols for these kids. In the first instance, she must read African languages and then secondly, she must live in a world where Africa is represented and represented on its own terms. So for me that was a big motivator. You stay up at night thinking, ‘Shit. We are gonna read Minnie Mouse again. Like, we can’t.’”

Because of her belief that when it comes to literacy development “we grow with things over time”, Mkhize and her team made the decision to pitch the book for children between the ages of eight and 13.

Although the production team spent a lot of time fussing over aesthetic decisions — such as “that black people must look like black people, they mustn’t look like a caricature or stylised either” — Mkhize says just as much time was expended on what to leave on the cutting-room floor, because the book is just 34 pages.

“Making decisions for us was so multilayered,” she says. “Of course, I didn’t include an important section on human evolution. South African parents are not yet accustomed to the history of human origins on the continent. You picked that up when they discovered Homo naledi and there was a lot of backlash from the politicians and very high-profile people because as [black] South Africans we have been raised as, on one side you have Christians, and then we hate the scientific racism that said we were the lowest in the rung.

“So I began the story with the idea that all humans come from Africa. So it will [be] up to the parents to decide what they tell the child [further].”

Mkhize believes the book manages to walk the fine line between “here is a history and here is an ideology”. As such, the book positions the continent as “important and central to history” but the tone is not “too much on a super Afro-centric” path. “Kids must know that there is a world in which Africa operates and the world operates in Africa,” says Mkhize.

In as much as the book is for children, parents have their work cut out for them too. In the chapter on post-independence, for example, Mkhize writes: “Many countries struggled to implement democracy and there were many wars after colonialism. Some colonialists gave over political power but kept economic control over free countries.”

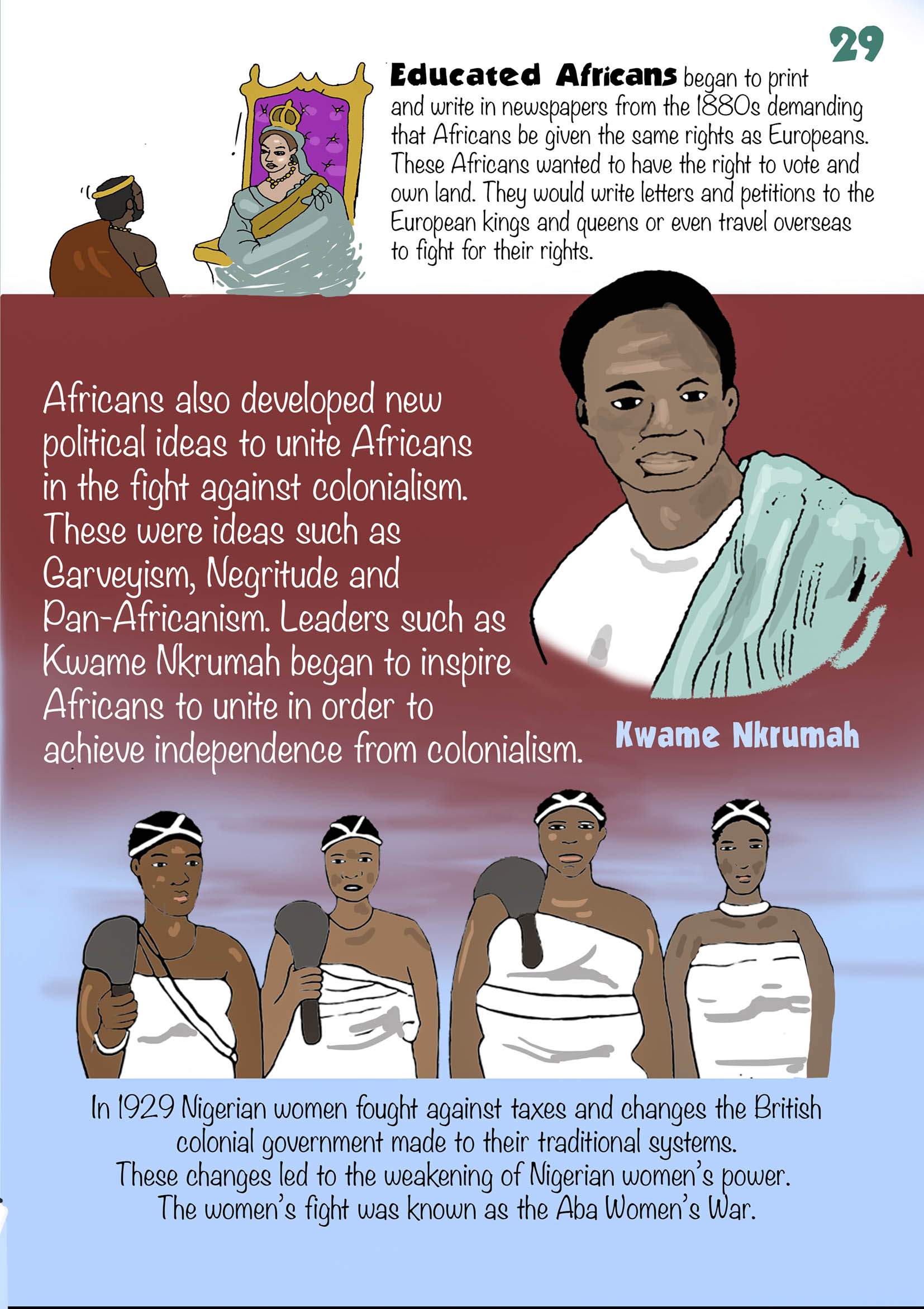

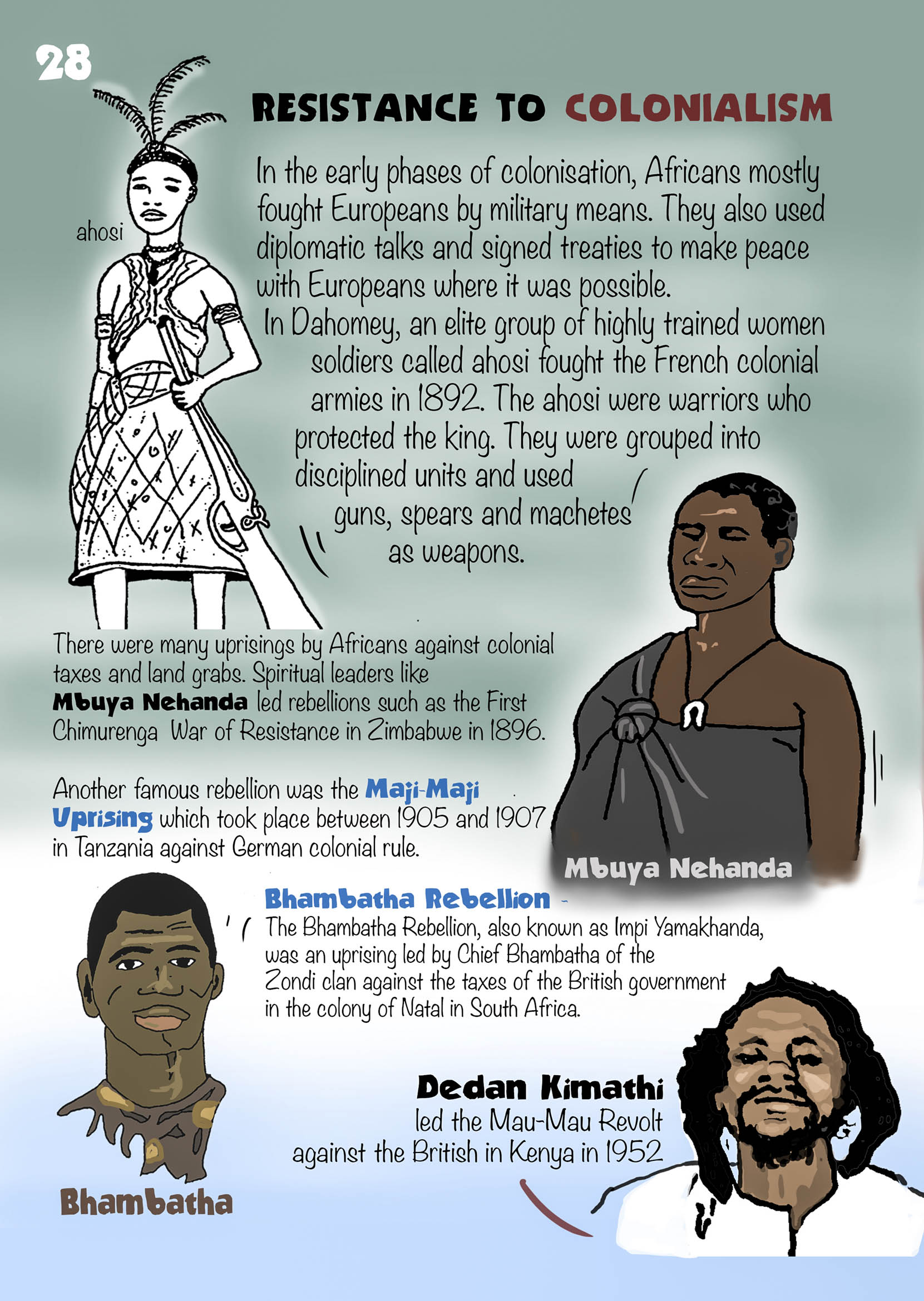

Illustrations from In Africa with Avi and Kumbi by Nomalanga Mkhize (Phaphamani Children’s Literature)

It is a page illustrated by images of Patrice Lumumba, Mobutu Sese Seko, Thomas Sankara, Wangari Maathai and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. My nine-year-old mind would definitely wonder out loud what the term “assassination” means, for example, and what it has to do with economic control of so-called free countries. And then it would wonder why Sirleaf was the first elected female head of state in Africa, as late as 2006.