Gifted: Elsa Joubert has received awards and honorary doctorates for her contribution to literature. (Natalie Gabriels/Gallo Images/Foto24)

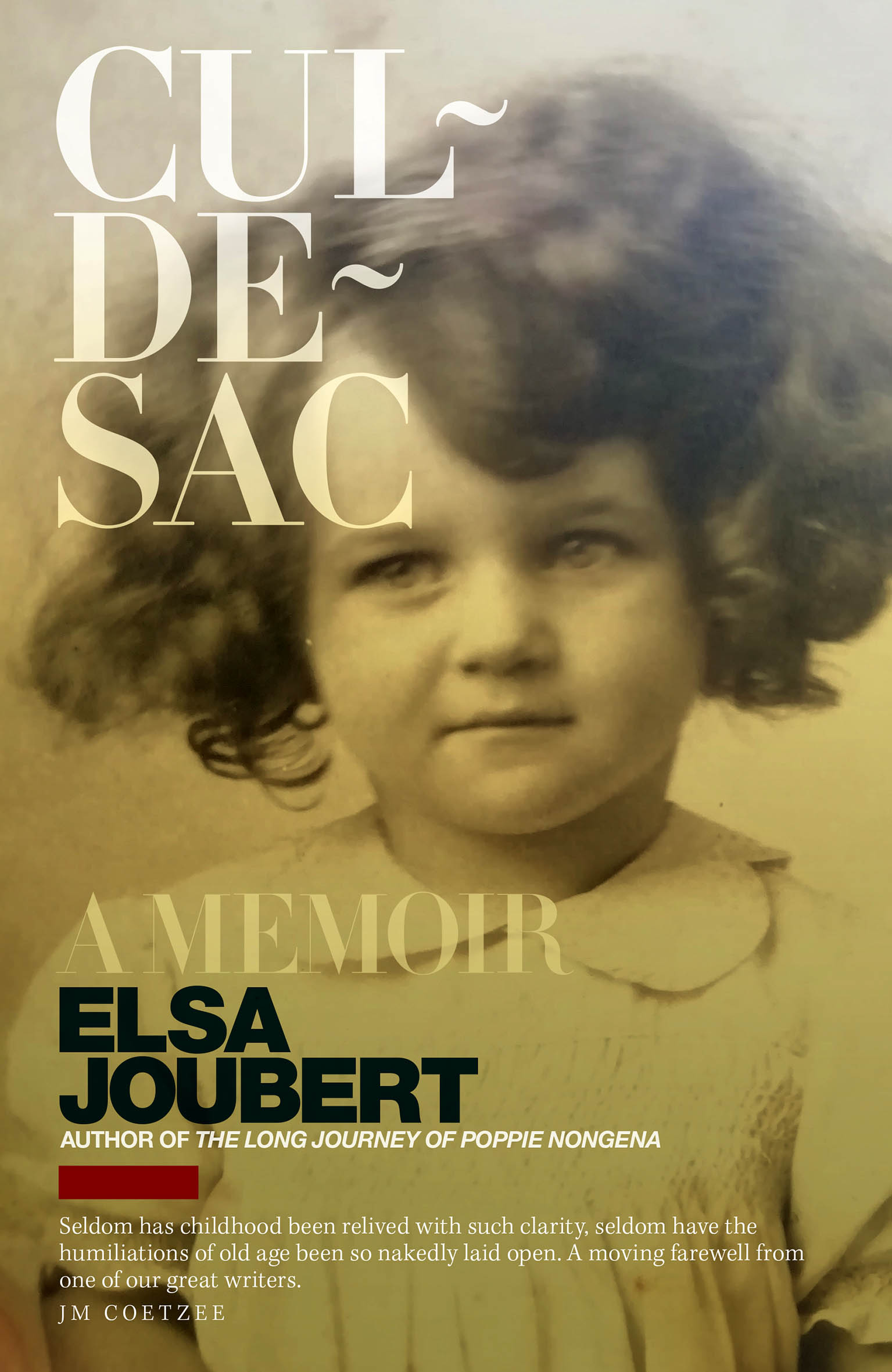

Elsa Joubert, one of South Africa’s most famous authors —her book The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena was translated into 13 languages —is now in her 90s and living in an old-age home. In her memoir Cul-de-Sac (Tafelberg), she wryly muses on life and relationships. This is an edited extract

With the passing of time and the aging and weakening of the residents, they die three or four per year, almost as if in waves. Sometimes more.

Several of them leave a great void in my existence. We had become friends. Like Jo Struik. She was in her early 90s when she died. Her health was bad – she suffered from extremely low blood pressure – and when she walked to my apartment, she’d be out of breath.

I had coffee with Jo in her apartment with the typically Dutch interior, dark and heavy, with a view over the bay. There was a framed portrait of her family on the wall: Cees, her husband, and three younger men, all blond and attractive. With them was a woman in middle age, also blonde and tall, clearly related to them.

“That photo was taken when I was at my happiest,” Jo said.

“Who is the woman?”

“It’s me. You won’t believe it, but I was also tall. We all shrink here in Berghof.”

Oh, I thought, that’s why my grandson Nicolas has to stoop so low to kiss me … I thought it was his growing, is it my shrinking? The prospect is dreadful.

She told me more: “Cees, my husband, survived for two years in the Burmese jungle as a lay preacher for the prisoners. But for the Dutch the war was not over: Indonesians who wanted to claim their freedom and the Dutch who did not want to forfeit their colony. We were sent to the island of Bali where our first son was born.”

Repatriation to Holland, eventually, and Jo pregnant with their second son.

“We were a debilitated, shivering, devastated little group of people who stepped ashore in Rotterdam from the large former passenger liner, itself rather battered after war service. Dumped into the Dutch winter in our ragged, prewar summer clothes.

“After life in the balmy, evergreen emerald islands of Dutch India we could not get used to grey post-war Holland and the taciturn, slightly disapproving, high and mighty Dutch.”

When his old firm offered Cees a position in their bookshop in the Cape of Good Hope, they accepted it gladly.

“When we sailed into Table Bay, we knew, this was our home.”

Here another son was born.

Jo was a woman with a sharp mind. She stayed informed about not just South African events, but also Dutch politics; she could hold her own with any expert.

I first met her in the 1970s. At the time I was very much focused on the new black writers of Africa. In particular I tried to introduce the Afrikaans reading public to their books on the books page of Die Burger.

The books were difficult to come by because so many were banned by the Censorship Board. Then I heard that Struik’s bookshop in Wale Street stocked the African Writers Series of the British publisher Heinemann. That was a find.

I’m kneeling in front of the half-shelf of thin paperbacks to which the assistant has taken me. I hear a clear voice with a pronounced Dutch accent saying next to me: “May I help you? This is our speciality, even though we sail very close to the wind sometimes.”

It was Jo. She helped me countless times to get hold of banned books. I find it wonderful to think that our paths, hers from Dutch East Indian Batavia, mine from Cape Dutch East India, could meet here in Berghof. As with billions of other people on the globe we are contemporaneous earthlings, fellow travellers, coming forth together from the unknown and fated to return together into the unknown. Our principal fellow travellers are our parents. When they die, we feel abandoned; but then the next generation is arising triumphant on the horizon already.

Cees, a bibliophile with a strong Dutch academic background, later started his own bookshop in Cape Town. With her quick head for figures, Jo did the bookkeeping. They concentrated in particular on the buying and selling of Africana, and when this market was exhausted Cees started marketing facsimile editions of rare South African writings, among others the Jan van Riebeeck diaries.

He died young. With two of her sons Jo carried on the work, for as long as she could. Then she came to Berghof. Always neat, the silver hair stylishly cut. Fluent in Afrikaans, but a strong Dutch accent in English. Before her 90th birthday she translated her whole life story from Dutch into English so that her American and Australian grandchildren could also read it.

Shortly before she died, she was admitted for a few days to the hospital across the way for observation.

I’m standing next to her bed. Through the windows we see the slopes of the mountain, shades of dark and lighter green against the blue. The afternoon sun is shining benignly, it’s a windless day. One of her sons stands on the other side of the bed. Between us lies the tiny person under the white sheets, against the white pillows. All three of us know that she will die.

Something comes over me, brings home to me that this is a portentous moment. I think of the tremendous task these young Dutch people came to fulfil at the Cape. With the publishing house Struik they extended the borders of our book industry and opened up new vistas. Our historical awareness was intensified by their facsimile impressions of old historical books. The standard of beautiful books was established for ever. I look at her son and then at her. I have a lump in my throat.

“Thank you very much, Jo, for what you, your husband and your sons did for us here at the Cape. I honour all of you for it.”

Tears stream over the small, wrinkled face. She says nothing, but she squeezes my hand.