In contemporary India, hyper-capitalism is articulated to hyper-nationalism via a violent authoritarianism, organised through both the state and popular forces. (Reuters/Adnan Abidi)

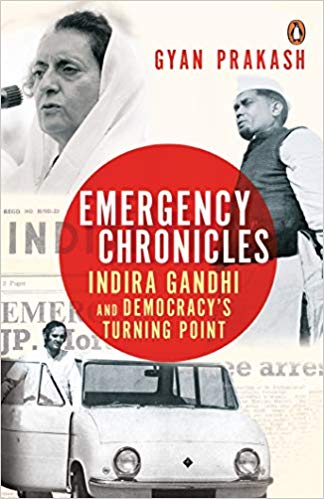

In 1975, Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi found herself confronting popular ferment and declared a state of emergency. In his compelling new book, Emergency Chronicles, Gyan Prakash argues that the emergency was a response to popular protest that escalated as it became evident that independence had failed to realise its promise of democratic transformation.

In Prakash’s analysis the turn towards authoritarianism was not a temporary intervention that preserved the existing order. On the contrary, “Hindutva and market liberalisation emerged out of the emergency’s ashes to meet the tests posed by popular mobilisation.”

In contemporary India, hyper-capitalism is articulated to hyper-nationalism via a violent authoritarianism, organised through both the state and popular forces. Not entirely unlike European fascism in the 1930s, social stress is displaced into the horizontal scapegoating of vulnerable minorities to displace the risk of vertical confrontation.

This offers an authoritarian means to contain the political crisis produced by the popular discontent that arises from a deep social crisis. It may be an effective form of containment but it is not compatible with substantive democratic commitment.

Prakash returns to BR Ambedkar’s prescient warning, delivered in 1949, that: “In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality … We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy.” Prakash writes that for Ambedkar democracy should not be reduced to holding elections but must be “a value, a daily exercise of equality of human beings”.

By this measure South African democracy has been a miserable failure for the majority, who remain impoverished and spatially excluded, subject to routine forms of institutional contempt and terrifying rates of criminal violence, often denied even the abstract rights of liberal democracy in the name of tradition, governed with increasing state violence and at risk of repression if they have the temerity to organise outside the ruling party.

It is 25 years since the ANC’s ascent to state power, and 15 years since popular protest in the form of burning tyres and road blockades started to become a routine feature of ordinary life. But despite the scale of discontent, no national force that could build a form of popular organisation with the strength and commitment to enable a democratic resolution of our social crisis has cohered. At the same time, there is no political party genuinely committed to building popular democratic power, and no party that can offer a serious challenge to the ANC at the hustings.

The faction of the ANC taken to be led by secretary general Ace Magashule, and actively supported by the Economic Freedom Fighters in significant respects, is committed to a kind of political gangsterism, legitimated by hypernationalism, in which a political class profits from the state at the expense of citizens.

It is a form of politics that may threaten or displace some forms of white domination but can result only in a profoundly authoritarian, violent and unequal society. One just has to look at Mpumalanga under David Mabuza, the Free State under Magashule, or Durban under Zandile Gumede, to get a sense of just how grim things would be should this form of politics come to dominate society.

The faction of the ANC led by President Cyril Ramaphosa includes people who aspire to the wholly fantastical idea that there can be some sort of return to the way things were before Jacob Zuma stormed the political stage. That hope is forlorn for the simple reason that a return to the economic and political arrangements that collapsed the Thabo Mbeki presidency will, in time, do the same to a Ramaphosa presidency. This is because Ramaphosa and his allies are bereft of any concrete ideas as to how to effect this return in a manner that will enable a viable path out of impoverishment for the majority.

Ramaphosa’s opposition to corruption, a phenomenon that is popularly despised, has won him and his faction some sense of legitimacy. But this is limited and will prove to be impermanent as it becomes clear that the social crisis is worsening.

The logical solution for this faction would be to attach itself to the popular anger against corruption, sometimes expressed in militant forms of protest, and to offer immediate and significant concessions to the most organised and mobilised parts of this constituency through strategies such as rapid urban land reform, and the right to recall local party representatives.

But, although this faction may have some of its roots in the trade union movement and the popular struggles of the 1980s, it is now too elitist to pursue a serious attempt to ally itself with popular forces and sentiments in a potentially democratising project, one that could sustain its credibility in society and secure its authority in the party by routing widely loathed local political bosses.

Ramaphosa is not unaware of the political impossibility of the fantasy of a return to the way things were before Zuma, but now with added austerity. Although often absent from the national debate, or present in a manner marked by an insipid inability to grasp and seize the moment, he has made two significant moves that indicate an awareness that the subordination of society to the market will be a difficult sell.

One of these has been to join the Democratic Alliance in a scurrilous turn to explicit attempts to incite xenophobic sentiments. The other has been to repeatedly note his attraction to authoritarian states, such as Paul Kagame’s regime in Kigali. He is not alone in his attraction to Kagame, which is shared by pro-business figures such as Tito Mboweni and Herman Mashaba.

Rich Mkhondo, an intellectual firmly embedded in elite circles, has taken matters a step further and, in the Sunday Times, openly called for dictatorship. Mkhondo says he is for an enlightened despotism “that will exercise absolute power over the state, but for the benefit of the population as a whole”. His list of “benevolent dictators” includes a figure as chilling as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

In January 2018, The Guardian reported that Erdoğan’s political clampdown had resulted in criminal investigations into 150 000 people, 50 000 people imprisoned on remand, more than 100 000 public sector employees arbitrarily dismissed under state of emergency powers, including hundreds of academics and a quarter of the judiciary, and at least 100 journalists jailed.

Mkhondo is not part of some lunatic fringe confined to Twitter. He is a person with significant power, writing in the largest-circulation newspaper in the country. He speaks for a faction of the elite that actively and openly desires an authoritarian resolution of the crisis.

If the faction of the ANC that has made its fortune from accommodation with the market can fend off the faction that aspires to accumulate wealth from the state, it may very well find itself confronting significant popular discontent and seek to win wider support for a more authoritarian path.

This is not to suggest that Ramaphosa’s trajectory is likely to end up in a position as extreme as Narendra Modi’s in India. Modi has spent his entire life in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a far-right organisation inspired by German fascism that has spent almost a century preparing itself for an authoritarian form of hegemony. The ANC includes authoritarian currents but, thankfully, none of them are remotely analogous to the RSS.

Nonetheless, we should not assume that we will be immune from the deep structural forces that have contorted democratic aspirations in a country such as India or, for that matter, Algeria or Zimbabwe. An authoritarian resolution to our crisis is clearly far more likely than an attempt at a democratic resolution.

We should not underestimate the extent of our crisis. The scale of unemployment, particularly among young black people, is staggering and not sustainable. Recently, Bongani Cola, the deputy chairperson of the Democratic Municipal and Allied Workers Union of South Africa in Port Elizabeth, was assassinated outside his home in New Brighton. During the following weekend, 13 murders were reported in Philippi East in Cape Town.

A society in which events like these are matters of minor national interest in a more or less ordinary week is already in serious trouble.

In this uncertain and perilous situation Ambedkar’s insistence that democracy must be “a daily exercise of equality of human beings”, and his warning that a failure to translate formal political equality into “social and economic life … will blow up the structure of political democracy” is an urgent warning to a society that, although already in crisis, and subject to often violent forms of authoritarianism at the local level, has not yet sought to make an explicit attempt to manage popular discontent with authoritarian measures.

Richard Pithouse is an associate professor at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, the co-ordinator of the Johannesburg office of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research and the editor of New Frame.