(John McCann/M&G)

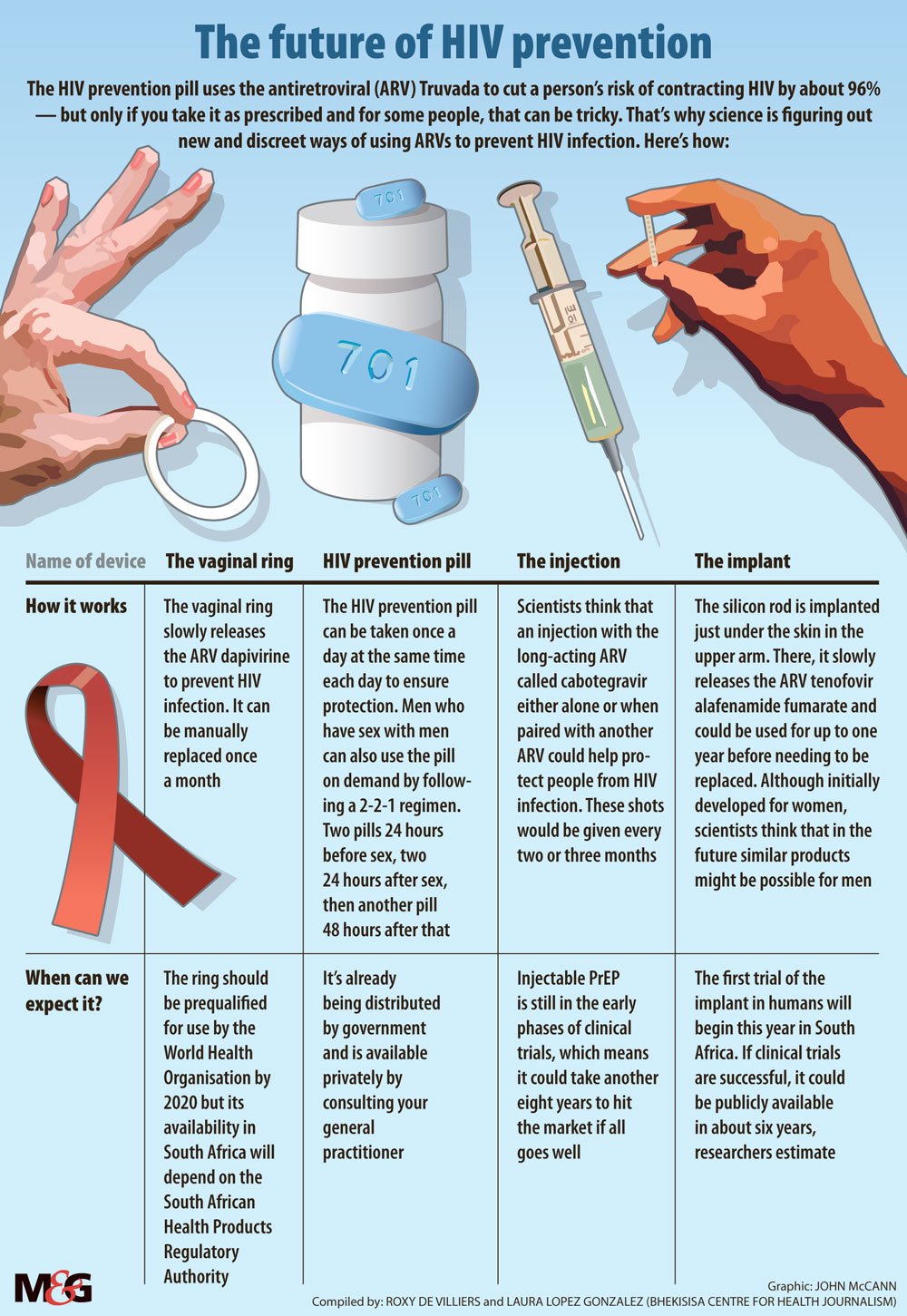

The HIV prevention tablet is now available in South Africa but popping a pill every day to stay HIV-negative may not be for everyone. For young women, hassle-free alternatives are on the horizon.

A vaginal ring inserted monthly could reduce women’s risk of contracting HIV by 63%, according to a recent study.

The ring is loaded with the antiretroviral drug (ARV) dapivirine, which is slowly released into wearers’ blood to help prevent HIV infection. The flexible, silicon band — developed by the nonprofit organisation International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) — is the first long-acting form of treatment that HIV-negative women can take before being exposed to HIV to reduce their chances of contracting the virus. The treatment, which is also known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), can be easily replaced at home each month.

In 2016, research conducted among almost 2 000 women in Uganda and South Africa found that when women inserted the ring and kept it in for the full month, the device reduced their risk of infection by 31%.

The results of the study were published in The New England Journal of Medicine. Another similar study — also published in the journal and conducted in four countries in southern and East Africa — had similar findings.

But both trials found differences in how well the ring worked for women based on age — mostly because women younger than 21 were less likely to use the ring consistently, researchers hypothesised, and they were likely having more sex than older women.

After the initial study concluded in Uganda and South Africa, scientists continued to follow ring-using women who had remained HIV negative during the trial for at least one year. They found that not only did 95% — 12% more than in the previous study — of women use the ring at least some if not all of the time, but also that the silicon band was more effective at protecting them from HIV than previously thought. The research was presented at the South African Aids Conference in May. When researchers compared the women’s results with computer simulations of what would have been their HIV risk without the loops, they found that the ARV-containing ring reduced new infections among the group by almost two-thirds.

IPM’s chief medical officer Annalene Nel says the organisation plans to submit the ring for approval to the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (Sahpra) and its United States counterpart, the Food and Drug Administration, later this year.

The band is already being reviewed by the European Union’s drug authority, the European Medicines Agency. If the agency greenlights the ring’s public use in the EU, IPM will submit it for World Health Organisation (WHO) prequalification. This kind of WHO approval often allows devices to be used in low- and middle-income countries that don’t have national regulators with the capacity to quickly approve new medicines or products.

The IPM expects the ring to be WHO-prequalified by mid-2020 and approvals from several national regulators in Africa to follow, says the senior director of IPM external affairs Africa, Leonard Solai.

The IPM is also in the early phases of developing two other dapivirine-containing rings that could be left in for three months at a time or could combine the HIV protection of an ARV with a long-acting contraceptive. A two-in-one ring could cut down costs for women, for instance, the money spent on transport to collect birth-control from clinics that are at times few and far between.

But, what does this form of PrEP mean for women in South Africa?

Three times as many young women between the ages of 20 and 24 are HIV-positive compared with men their same age, preliminary results of the Human Sciences Research Council’s latest household HIV survey show.

The department of health wants to slash the number of new infections by rolling out PrEP to young women in the form of a daily HIV prevention pill as part of the country’s latest HIV plan.

But studies have shown that young women’s adherence to the pill is considerably lower than that of, for instance, men who have sex with men, because young women often don’t perceive themselves to be at risk of HIV.

Because the dapivirine ring only needs to be replaced once every month and maybe in the near future, once every three months, it could increase womens’ adherence to PrEP — and consequently how well it works for them.

So, when can we expect a rollout of the one-month dapivirine ring in the country?

Nel says there’s still a long way to go before the ring would be available for public use — the IPM would first have to get Sahpra approval. “We’ll probably have to go into a fourth round of trials,” she concludes.