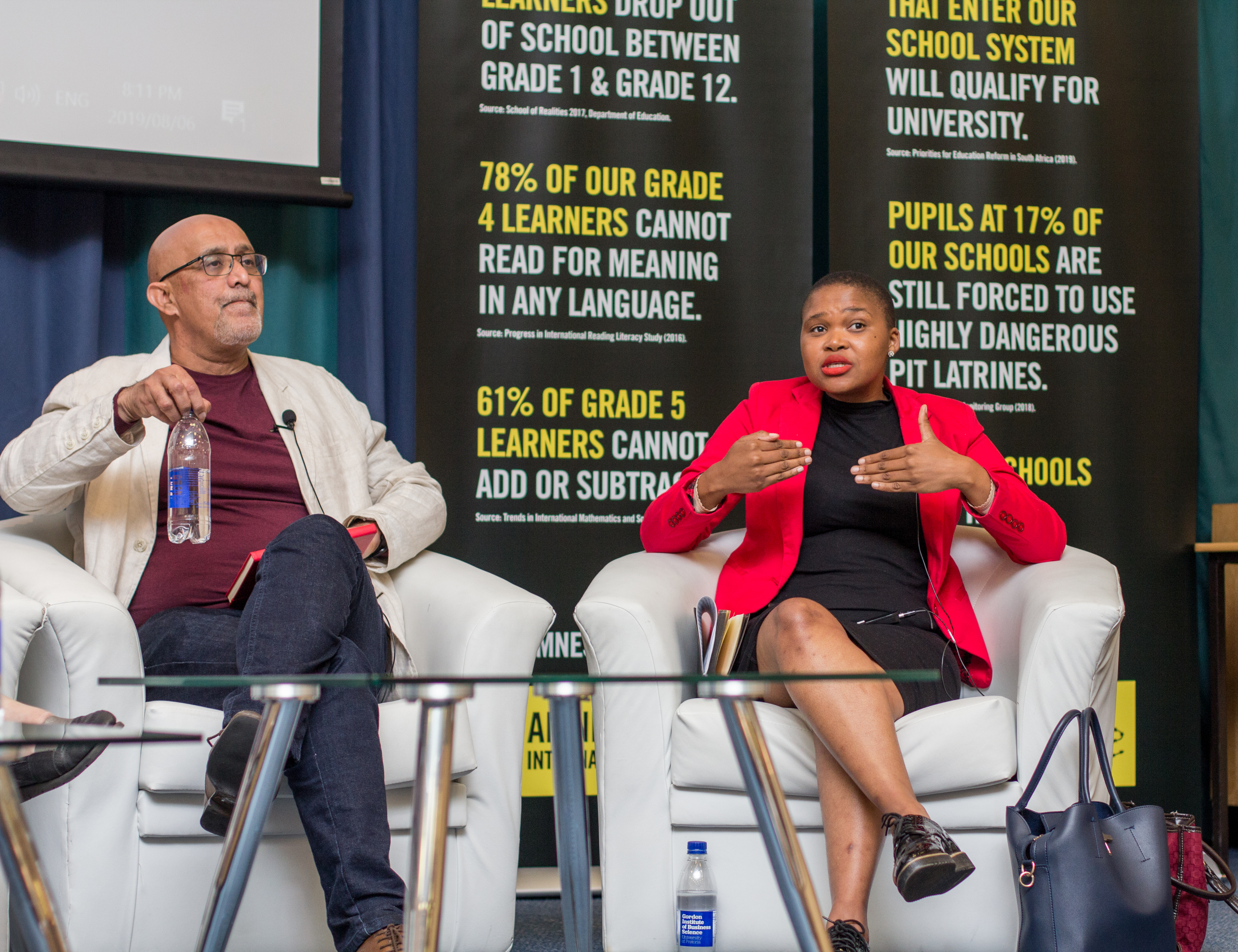

Panelists Siki Mgabadeli and Angelo Fick at the critical thinking forum centred on the education crisis in South Africa

The state of the basic education system should have South Africans toyi-toying in the streets, demanding urgent intervention. Even 25 years since liberation, our schooling system reflects the negative legacy of apartheid. Considering that our schooling reflects the people we are training to lead us into the future, we are heading for disaster. This was the message of the latest Amnesty International and Mail & Guardian Critical Thinking Forum, held on August 6 at the University of Pretoria’s Gibs Business School in Johannesburg.

The forum involved a panel discussion speaking about the measures that need to be taken to address the poor quality of the basic education system. Moderated by business journalist and producer Siki Mgabadeli, the panel comprised Auwal Socio-Economic Research Institute director Angelo Fick, accountant and analyst Khaya Sithole, chief driver of Champion South Africa Ashraf Garda, M&G education reporter Bongekile Macupe, and Amnesty International executive director Shenilla Mohamed. The panellists called on South Africans to petition the government for urgent and decisive action.

The forum was well-attended and the attendees comprised members of both the public and private sectors concerned with education. The audience was engaged and participative, keen to find ways to solve the education crisis beyond the manufactured outrage of awareness campaigns.

A member of the audience raises an issue at the forum

A member of the audience raises an issue at the forum

For the past year, Amnesty International has been collecting research on the state of education on the ground. This led the human rights organisation to launch the #SignTheSmileOff campaign.

Controversially, the campaign featured former minister of native affairs and prime minister during apartheid Hendrik Verwoerd as its face. In the campaign, Amnesty International urges the public to wipe the smile off Verwoerd’s face and face the current state of basic education. “If Hendrik Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid and apartheid education, looked back now, he would be smiling. Because unless we tackle the deep inequality he created in our education system, we risk fulfilling his legacy,” reads the campaign statement.

Amnesty’s research shows that almost 50% of learners drop out of school between grade one and grade 12. A shocking 78% of grade four learners cannot read for meaning in any language, while 61% of grade five learners cannot add or subtract. The infrastructure of South African schools is dismal too: 46% of schools lack basic sanitation, including 17% where learners are forced to use pit latrines. Unsurprisingly, given these statistics, only 14% of learners who enter the South African schooling system will qualify for university.

Panelists Shenilla Mohamed and Ashraf Garda

Panelists Shenilla Mohamed and Ashraf Garda

The campaign faced some backlash, especially for its use of Verwoerd’s picture. Mohamed said Amnesty used his picture to create a “disruptive shock” and “invoke outrage” in South Africa. Answering a question from the floor about how the messaging of the campaign was misconstrued, Mohamed said Amnesty was not stirring racism but highlighting a public problem. “It’s not about colour — it’s about every single one of us,” Mohamed said.

Amnesty International holds that all children have the right to a decent quality, basic education in a learning environment with safe and adequate infrastructure, Mohamed said. The right to basic education is also enshrined in the Constitution, but looking at Amnesty’s research Mohamed asked: “What has this government done to reverse what the apartheid South Africa has ingrained into the education system?” Mohamed said it’s unthinkable for the state to focus on the fourth industrial revolution when we don’t even have basic infrastructure at schools. “We need to tackle the inequalities in education system, because otherwise we will lose generations of children,” she added.

Panelists Ashraf Garda and M&G education reporter Bongekile Macupe

Panelists Ashraf Garda and M&G education reporter Bongekile Macupe

“We need to be more alarmed about the state of our education system,” Garda said. Garda questioned South Africans’ willingness to tolerate levels of mediocrity in our failure to address the poor education system, which is is a beneficiary of the apartheid. Referring to the recent general election that took place in May, Garda said politicians should have emphasised education as much as they did land. “We need to tell political parties that if you don’t deliver on education then you’re OUT,” Garda said.

For Fick, the education crisis goes beyond political parties, and he highlighted the need to solve a broken system. This would involve shifting public conversation towards education. “Someone looking in the public domain would not understand that education is important. In the public domain we reduce everything to celebrity,” Fick said. He also pointed out that the focus on heroism shifts focus from the broken system. “There is no individual ‘hero’ or party that will fix the problem. Instead, if a bad person gains power, the system enables them, and there is no accountability.”

A different party will not change the system either, Fick said. Even with the relevant qualifications, “you still won’t get a position in the political parties, because it’s about who you know”. He added: “Don’t change the party, change the system.”

Fick also said that the solution to the education crisis we are facing is not complicated. It’s about taking it back to the basics and focusing on reading, writing and understanding. “Literacy is crucial,” Fick said.

“If you care about the future of the country, then why don’t you care about the children?” Macupe asked. In her work covering education, Macupe has seen a failing department of education. Five-year-old Michael Komape fell into a pit latrine and drowned in 2014. This happened under the current department of education. Komape’s father is now involved in various projects in Limpopo to keep school children safe. “We can’t shift from government’s responsibility. It’s government’s responsibility to make sure kids have better education. We pay tax,” Macupe said.

Khaya Sithole raises a point during the forum discussions

Khaya Sithole raises a point during the forum discussions

Sithole also emphasised how important it is for the basic education system to be effective. While the small upper and middle classes can afford to discard public education in favour of private education, the majority of the population cannot. “Some people don’t have an option to opt out. There will be no social mobility [for these people] because they won’t be able to make it through the poor schooling system,” Sithole said. This will have detrimental effects in the years to come, Sithole said, asking the audience what this picture could look like in 30 or 40 years.

The education system also needs to be separated from the politics of the day, he said. “The gap between what the government says and what the government does is costing us. Access must be matched with opportunity, or it won’t exist at all,” Sithole said.

The audience left with the sentiment that South Africa needs to take urgent stock of where the education system is and where it needs to be before we find ourselves in an even worse situation in the next few decades. As Mohamed said, as much as it is the government’s responsibility to deliver on education: “We are also part of the problem. We are not taking the injustice personally. We need to take our outrage out of our cozy homes and gated communities and stop pretending the problem doesn’t exist,” Mohamed said.