Question marks: The 2019 version of the NHI Bill proposes more centralisation, which creates potential for corruption, and there is still much confusion about the role of private medical schemes. (Oupa Nkosi)

NEWS ANALYSIS

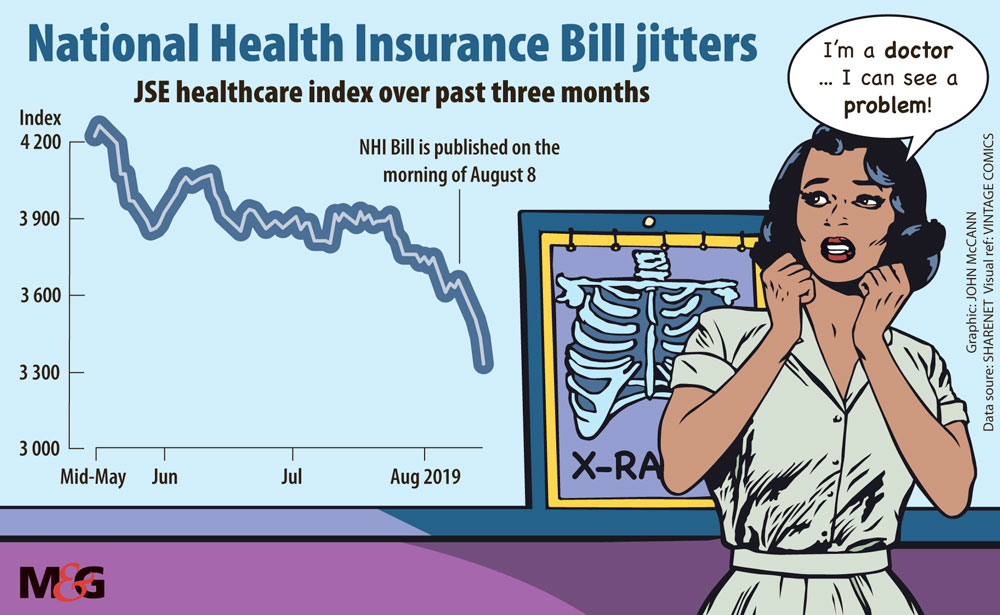

Despite all the assurances Health Minister Zweli Mkhize gave that the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill does not spell doom for the private healthcare sector, the market was sceptical, as the shares of a number of healthcare and pharmaceutical companies took a hammering following its announcement.

The Bill — which was released last Thursday and sets out the architecture for an NHI fund — reignited questions over the future of private healthcare once the scheme is set up. Among the changes outlined, the proposed legislation states that medical schemes will be able to offer only “complementary cover” to the services that the NHI fund will provide.

At least one healthcare expert has warned that the Bill will introduce the same level of uncertainty into the healthcare sector in South Africa as has been seen in the mining arena. But others have argued that the Bill should be viewed as an opportunity to correct the currently fragmented and iniquitous healthcare landscape.

In the two trading days following the NHI Bill’s release, the JSE’s healthcare index lost more than 6%. Discovery, which administers the country’s largest private medical scheme, was hit particularly hard, losing more than 11% over the same period, while the likes of pharmaceuticals firm Aspen and private hospital group Mediclinic saw their shares decline by about 12% and 3%, respectively.

Discovery’s share price had been falling prior to the Bill’s announcement, said Wayne McCurrie of FNB Wealth and Investments. This is partly due to concerns around the bank it is aiming to launch, as well as the general economic downturn in South Africa in recent months.

But in the days since the NHI’s announcements the declines could be linked to the NHI, McCurrie said, as could the contractions in other healthcare stocks.

The spooked market notwithstanding, the NHI still had “a massive path to walk before [it] sees the light of day” said McCurrie. What was released last Thursday is just the start of the parliamentary process, he said, and NHI would not be enacted in the form set out in the Bill “simply because it is unaffordable.” This was instead the first salvo in what is likely to be a long negotiating process, McCurrie argued.

But Alex van den Heever, the chair for social security systems administration and management studies at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance, argued that the effect of the NHI proposal — which he believes is unimplementable — will be to create the same policy uncertainty that has plagued the mining sector.

“They are doing in healthcare what was done in mining — putting a risk premium on everything,” he told the Mail & Guardian.

The state will maintain a continuous narrative around its plans for NHI, while being unable to implement it, leading to persistent policy uncertainty, van den Heever maintained, At the same time it will fail to address the flaws in the current system, he argued. “Nobody will really be able to stand still and plan,” he said.

Costs remain unclear

Critically, the Bill remains uncosted despite longstanding concerns that it may be simply too expensive to implement, particularly under existing fiscal constraints. At the launch, Mkhize did not want to elaborate on the costs NHI would entail until the treasury has published a paper on the funding of the NHI.

But the Bill outlines plans to raise the money, including the shifting of funds from the provincial equitable share and conditional grants into the fund; the reallocation of funding for medical scheme tax credits (currently an estimated R18-billion) paid to various medical schemes to the fund; additional payroll taxes for employers and employees; and a surcharge on personal income tax.

According to Peter Attard Montalto, head of Capital Markets Research at Intellidex, public healthcare spending this fiscal year is R223-billion, with an additional R237-billion spent in the private sector. Referencing work done in a 2017 report from the Davis Tax Committee into funding the NHI, he said in a note that NHI is expected to cost an additional R165-billion from 2026.

Under current circumstances, Intellidex calculated that paying for NHI would require a 2.7% payroll tax, 2.7% surcharge on taxable income and 3.5 percentage point VAT increase — and this would address only the NHI shortfall, not wider revenue shortfalls. “Overall, we think NHI is unworkable in the current economic and fiscal context, even if sorely needed. Indeed, it can do more harm than good at a macro level,” he said.

Van den Heever put his view more bluntly: “There is no costing because this nonsense can’t be costed.”

The NHI cannot work, he argued, because of the governance framework of institutionalised patronage, which has systematically destroyed the integrity of the public health system, and many other departments, together with state-owned enterprises.

The Bill proposes to centralise what should be decentralised, he continued, adding that: “The purchasing function should be not be placed within a national structure, as this is too distant from delivery and will institutionalise massive inefficiencies.”

Finally, what would amount to an increase in taxation by about 3% of gross domestic product to cover medical scheme members is fiscally absurd and cannot be achieved, said Van den Heever.

Pros and cons

Apart from a few significant exceptions, the Bill remains very similar to its 2018 iteration, according to Sasha Stevenson, the head of health at nonprofit organisation Section27.

Certain changes, however — notably relating to the centralisation of power to the ministry of health — had intensified risks that Section27 had already identified in the 2018 version.

“The 2019 Bill sees even more centralisation,” said Stevenson. Where previously various processes and appointments went through Parliament these governance and accountability mechanisms now rested with the minister.

“When everything is too centralised there are risks … That is one of the main changes and that is a change in the wrong direction,” Stevenson said.

Another significant change was the introduction of an office of health products procurement. The entity will be responsible for the “centralised facilitation and co-ordination” relating to the procurement of items, including medicines, medical equipment and medical devices.

In theory this may be a good move, as it looks to leverage the ability of central buying to reduce the price of these critical items, but there is not enough information about how this office will be managed and governed, she said. This is particularly important as, globally, health procurement is a problematic area and “is a source of financial irregularities and corruption”, Stevenson noted.

The Bill permits private medical schemes to provide complementary services — or those not provided by the fund — but what this will mean in practice is not clear, as the package of health services that the state will provide is still not known. “The position of medical schemes remains a bit of a question mark,” she said.

Other issues, notably the role of provinces in relation to entities outlined in the Bill, such as district health management offices, and the contracting unit for primary care, remain unclear, despite more information on them, Stevenson noted.

“It’s not clear how all these structures will relate to each other, how money will flow, how accountability will flow, and how the different bureaucracies that will be built into the system will be paid for,” she said.

The 2018 version of the Bill sparked consternation in the treasury, notably over the fate of medical schemes, as well as the “massive uncertainty” it introduced into the intergovernmental financing system and the location of health functions.

The treasury’s concerns were revealed in a leaked letter written to Olive Shisana, the adviser to president Cyril Ramaphosa on the NHI, as reported by health publication Spotlight.

In response to questions, the treasury said the new Bill partly addresses concerns about medical schemes as, under section 33, it continues to allow for the duplicate role for medical schemes until NHI is fully implemented, which is expected in 2026. Similarly, the Bill partly addresses some of the concerns about provinces through section 3(4), “which clarifies that health sector funds will not shift until relevant legislative functional changes within the health sector are affected in relevant legislation”.

But not everyone is as negative about the Bill. Russell Rensburg of the Rural Health Advocacy Project cautioned against perpetuating a narrative that framed the public health sector as simply in a state of crisis and the NHI as a cost to the economy, rather than an investment in the health of citizens.

“As long as we are framing the public health sector as in crisis, we become … beholden to private sector deliverers,” he said.

It was too early to cost the NHI, as the basic package of services has yet to be outlined and evaluated against what is already provided in the public sector and what is needed to address existing coverage gaps, Rensburg said.

The state is already budgeting to spend more than R240-billion on healthcare in the next two years, he said, and there is already a whole package of services available. These existing resources can be deployed more strategically and efficiently.

“We spend a considerable amount of money and I think at the moment that money is just not sweating enough,” he said.

Mining public expenditure for increased efficiencies alone could raise a substantial amount, he argued, while the introduction of central purchasing has been shown to drive down costs.

“We can’t be trapped by fear that something is going to go horribly wrong and at the same time allow the abuse of the private sector in the medical schemes environment to continue,” said Rensburg.

“We have to fix the entire health system and we have a fantastic opportunity to do it now.”