The IMF and the government said earlier this month that the country hasnt reached the point where a bailout is needed.

COMMENT

There is no debating that South Africa’s fiscal finances are in a dire state.

The expansion in government spending that immediately followed the 2007-2008 global financial crisis has been supplanted by a decade of loose fiscal policy and sub-par macroeconomic growth. Before accounting for the inevitable realisation of Eskom’s contingent liabilities to the fiscus, South Africa’s “lost decade” has resulted in the doubling of government debt — from 26% in the 2008-2009 fiscal year to 57% (and counting) at present.

Against a backdrop of weak government finances and sickly economic growth there is disquiet about the prospect of South Africa approaching the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financing.

Yet the IMF — and the government — said earlier this month that the country hasn’t reached the point where a bailout is needed.

Two key questions need to be answered to determine whether these fears of having to turn to the IMF are well founded: Does South Africa fail a debt sustainability assessment and is South Africa’s capital market access at imminent risk?

First, central to determining South Africa’s debt sustainability over the medium term is an examination of the country’s debt profile and debt burden indicators. To avoid a debt trap, what we ultimately need to form is a credible view that the primary budget surplus required to stabilise the country’s debt burden is attainable in the medium term.

In this economic environment, a primary budget surplus in the medium term (the forthcoming five years in IMF lexicon) will only realistically be achieved through average economic growth in excess of 2.6% over the next five years, assuming all else is equal, or cumulative expenditure containment of R150-billion over this same period.

But, the domestic economy is inadequately geared to sustainably grow in excess of 2.6% in the medium term, so we can largely discount this as a solution to achieving debt sustainability. Mercifully, in preparation for the 2020-2021 budget, the treasury has issued a compulsory budget baseline reduction of 5% in 2020-2021 fiscal year, 6% in 2021-2022 and 7% in 2022-2023, which, if adhered to by government departments and public institutions, can be read as an important first step away from the fiscal cliff.

Related to the assessment of the sovereign’s debt burden is its debt profile. Despite South Africa’s burgeoning funding requirement in the past decade, the financing thereof has been astute. The deficit has been predominantly financed through the issuance of long-dated nominal bonds.

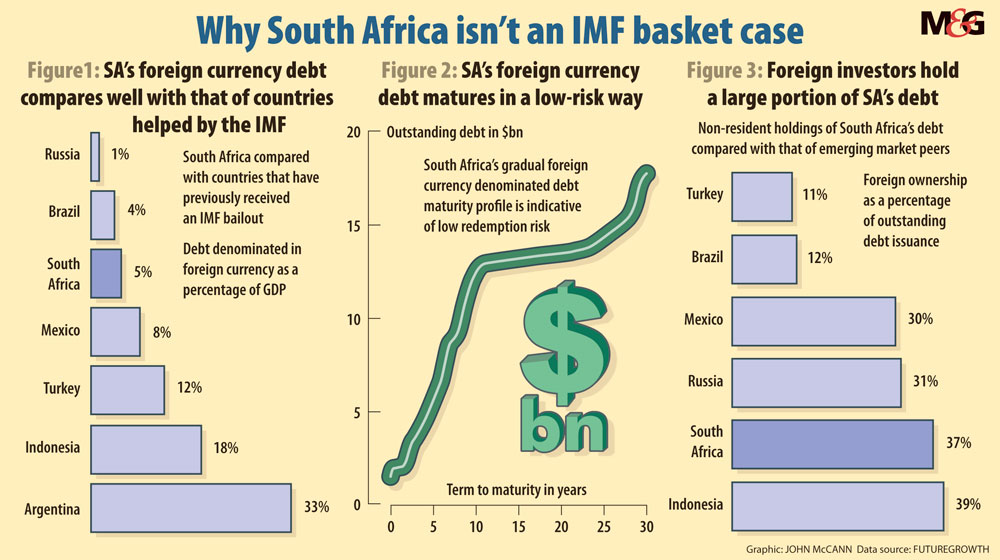

The treasury has shied clear of its 20% to 25% prudential limit to inflation-linked bond issuance and, most importantly, the “original sin” of foreign currency debt issuance has been well avoided, with a modest 5.5% of outstanding gross government debt denominated in foreign currency.

This is a crucial differentiator between South Africa and the basket of sovereign nations that have fallen off the fiscal cliff in the post 2008 crisis era (see Figure 1). Further to this, countries requiring an IMF bailout often do so because they have a pending debt repayment that they are unable to roll over. South Africa’s gradual foreign currency debt maturity profile suggests that foreign currency funding pressures remain benign, implying minimal redemption or roll-over risk (see Figure 2).

The importance of low foreign currency debt issuance coupled with a free-floating exchange rate regime, which by design acts as an economic “shock absorber” — adjusting as and when appropriate to facilitate a balance of payments equilibrium — cannot be overstated for the effective management of balance of payments risk. South Africa’s balance of payment’s risk is further buttressed by $41-billion in foreign currency reserves held by the South African Reserve Bank — equivalent to 5.8 months’ import coverage.

These assets, which include high quality foreign-denominated bonds and foreign currency, can be used by the central bank to both effect monetary policy objectives as well as to ensure payment of imports in the event of balance of payments distress.

To the second question, the currency’s high beta nature relative to emerging market peers is symbolic of the relative depth and ease of access of South Africa’s financial markets. Foreign investors’ access to South Africa’s financial markets is further illustrated by nonresident holdings of South African issued government debt, which is currently at 37% of outstanding issuance.

These foreign ownership statistics measure fairly relative to emerging market peers with comparatively deep, liquid financial markets (see Figure 3).

Consequently, although South Africa’s economic outlook hasn’t looked gloomier in the post-democratic era, it is still too early for the ignominious calls for external debt relief from the IMF. Significant time has been wasted, trust eroded and economic damage caused in the past decade, but there remains a brief window of opportunity for policymakers to swallow the bitter pill that is fiscal probity and resolutely enact growth-enhancing structural reform. South Africa’s sovereignty depends on it.

Refilwe Rakale ( research analyst), Yunus January (interest rate market analyst) and Rhandzo Mukansi (portfolio manager) are all employed by Futuregrowth