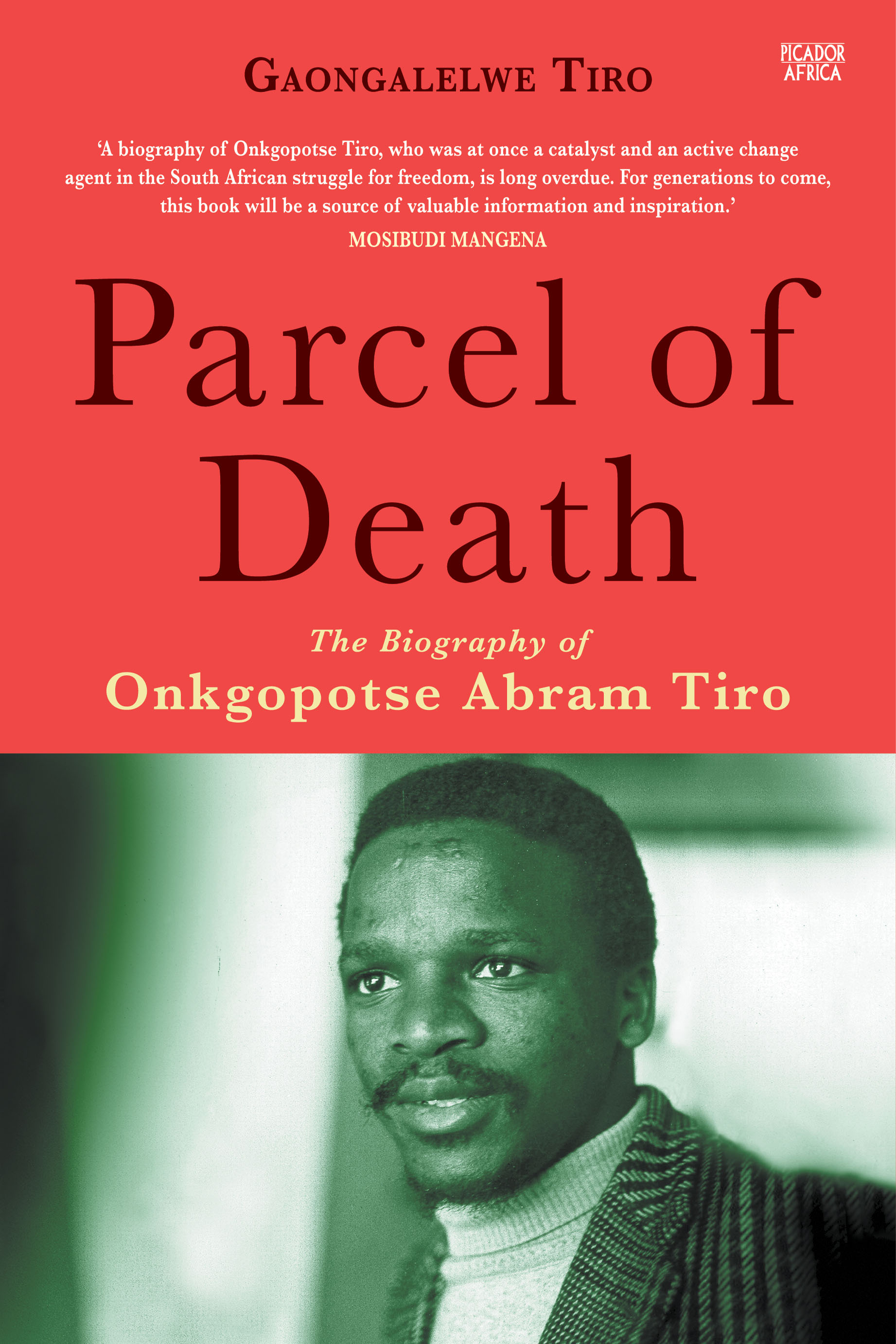

Black consciousness: Onkgopotse Tiro, was killed by a parcel bomb in Botswana in February 1974 but the apartheid government would not allow him to be buried in South Africa. (Sunday Times/ Gallo Images)

Parcel of Death: The Biography of Onkgopotse Abram Tiro by Gaongalelwe Tiro (Picador Africa)

“No struggle can come to an end without casualties. It is only through determination, absolute commitment and self-assertion that we shall overcome.” — Onkgopotse Tiro, message of solidarity to the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso)

This year is the 42nd and 45th anniversary of the deaths of two giant leaders in the Black Consciousness Movement, Steve Biko and Tiro, respectively. It’s also the 47th year since Tiro delivered his revolutionary address at the University of the North (then called Turfloop), in which he attacked the evils of apartheid divisions in tertiary education institutions. It lit the fire among the country’s youth, sparking nationwide protests.

I’ve always been curious to know more about Tiro and what exactly he did to be feared by some, yet also loved by so many. An in-depth biography provides answers. Parcel of Death: The Biography of Onkgopotse Abram Tiro, is written by his paternal nephew, Gaongalelwe Tiro. He has done a marvellous job in putting together such a book, researching and interviewing so many people about the life of this great man.

The book shares intimate anecdotes from Tiro’s early years growing up in Dinokana village near Zeerust and 25km from the Botswana border. Tiro lived with his grandmother, because his deeply religious single mother, Moleseng Tiro, was a domestic worker in Johannesburg.

Despite the hardship, Tiro had a normal childhood. He played soccer, swam in the river with his friends, herded the family’s goats and cattle, and hunted animals to eat (before he became a vegetarian while at primary school, after he was advised by his pastor to eat healthily). He also regularly assisted at a bakery run by the uncle after whom he was named.

In childhood Tiro already had a strong personality. He was very intelligent and very strict, which earned him respect from his peers; his friendliness, however, drew people closer to him. He was devoted to the Seventh-day Adventist church, attending it every Saturday.

The village helped shape Tiro’s revolutionary ideas because of its history in the fight against the oppression of indigenous people, and the conflict over their land and rights. Dinokana was also on the “underground railroad” for those leaving South Africa to join the war on apartheid.

From 1957 to 1960, there was no schooling in Dinokana because of riots against apartheid policies. During this time Tiro worked full time at a manganese mine, where he experienced capitalist exploitation first-hand. He was later promoted to dish-washer in the kitchen. He matriculated in 1968, taking 17 years instead of the usual 12 to complete his schooling.

Although Tiro was already conscious of the political situation, it was at Turfloop that his politics developed a revolutionary edge through his exposure to Black Consciousness Movement leaders Biko and Barney Pityana and the philosophy they propounded.

He became more militant and his stature grew as a Saso leader at the university and then as president of the Southern African Students’ Movement.

These students read widely and drew ideological inspiration from writers, such as Frantz Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre, as well as African leaders including Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere. They also identified with the Black Power Movement in the United States.

At the campus, the few white students were given preference over the black students for whom the institution was supposedly established. The administration was predominantly white. The chancellor, members of council and the registrar were all white. There were only five black academics. Such outright racism did not sit well with Tiro.

To make matters worse, he went searching for a Seventh-day Adventist church to worship at, but when he found one in a nearby town he was turned away because it was for whites only.

Tiro had a reputation of speaking truth to power. When the class of 1972 asked him, as a member of the student representative council, to speak on their behalf, no one anticipated the unfortunate chain of events that followed his valedictory speech. He spoke against apartheid policies, discrimination at universities and the control of black universities by the white regime, against stooge Bantustan leaders, and more.

He concluded his speech by predicting the inevitable freedom that would come for his people. He was summarily expelled and rendered persona non grata, which meant he could not get a job or be admitted to any university in the country.

Tiro took his fight against racial discrimination to his church, which resulted in the formation of the Memorandum Movement. Most of its members were young people and focused on decolonising the church. Its successes, which came in dribs and drabs, included adult education schooling and the election of a black pastor as president of the Southern Union, the regional body.

Later, with the support of the black principal of Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto and parents on the school board, Tiro was hired to teach the form 4 history class. He had many qualities that made the children take a liking to him; they talked enthusiastically about his teaching, which moved away from the rigid syllabus to challenge the poison of Bantu education. He also emphasised the importance of self-esteem. He made the children want to read beyond the prescribed books. He was compassionate, taking an interest in their personal struggles. He always had a Bible with him and always enjoyed a good discussion about politics or general social issues.

Contrary to what has been reported, Tiro didn’t teach the leader of the June 1976 uprising, Teboho “Tsietsi” Mashinini, in a classroom, but Mashinini was a frequent visitor to his home. Tiro took him under his wing and mentored him, sharing political literature that helped to develop Mashinini’s political consciousness.

But Tiro’s popularity did not sit well with some other teachers, who did not like him. He was let go in early 1973. The official line was that the school could no longer afford to pay him. But Tiro’s account was that a white school inspector had barged into his class and ordered him to stop teaching.

Then, learning that the police wanted to arrest him and slap him with a banning order, Tiro skipped the country and went into exile in Botswana. There, he lived an ordinary life (he liked jogging) until his death on February 1 1974, at the age of 28. He was killed by a parcel bomb — the first South African freedom fighter inside or outside the country to be murdered this way.

The apartheid government would not allow Tiro to be buried in the country of his birth. In 1998, Tiro’s family, with the assistance of the Azanian People’s Organisation, exhumed parts of his body from his grave in Botswana and he was reburied in Dinokana. He now has two shrines in two different countries.

There are still unanswered questions about Tiro’s death. One person linked to it is Craig Williamson, the apartheid assassin and spy, who infiltrated was heavily involved in the student movement in South Africa and internationally, who was later involved in the death, also by parcel bomb, of Ruth First. The parcel had a Swiss stamps and sender’s address — Switzerland was then one of Williamson’s bases. Jeanette Schoon (née Curtis), and her six-year-old daughter, Katryn, were killed by another of Williamson’s parcel bomb, which had been intended for Marius Schoon.

The Botswana authorities did not co-operate with attempts to establish the truth about Tiro’s death. His mother died a broken woman in 2003 after her pleas to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for an investigation into her son’s death went unheeded. She told Drum magazine: “Tell the world that the government has forgotten about us — the victims.”

To honour Tiro’s memory, the University of the North (now the University of Limpopo) named the hall in which he delivered his 1972 speech the Onkgopotse Tiro Hall. It has also named a bursary scheme, an excellence awards programme and a residence on the main campus in Mankweng after him. The university hosts the annual Onkgopotse Tiro Memorial Lecture.

Delivering the first memorial lecture in 2012, author and businessman Reuel Khoza said: “To me, the following are marks of the character of the man: courage, consciousness, conscientiousness, commitment, caring, compassion and passion, a sense of destiny and vision, a bias for action.”

The #FeesMustFall movement, which arose in 2015, drew on the efforts by Tiro and others to awaken people to the crisis in tertiary education. When, in August last year, Mcebo Dlamini walked from Johannesburg to Pretoria to deliver a memorandum urging President Cyril Ramaphosa to pardon students involved in the #FeesMustFall strike, he wore a T-shirt bearing the images of Tiro, Biko and Pan Africanist Congress leader Robert Sobukwe.

“It is [with] Tiro that even today we still clench our fists and put them in the air and cry inkululeko [freedom],” says Dlamini.

Wits student Mojuta Motlhamme writes in the social biography he researched on Tiro that he is “present and alive in the intergenerational memory of South Africans and is relevant when historicising the Rhodes and Fees Must Fall movements [because] he was a catalyst for student revolt in the 1970s the same way students stood up against injustices in 2015”.

Tiro’s angry spirit lives on.