The #FeesMustFall protest of 2015 began as a protest by students against fee increases at institutions across the country. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

The department of higher education, science and technology is working on a regulatory framework for setting fees at universities to ensure their affordable and that institutions are sustainable.

A task team — which was appointed early this year — comprising of academics and senior officials of the department has already started its work.

The idea of regulating fees in the university sector first surfaced in October 2015 at the ANC’s national general council. Then chairwoman of the party’s sub-committee on education Naledi Pandor told the Sowetan that delegates at the congress had raised concerns about the expensive university education.

She said it had been agreed that the department needed to look at a regulatory framework for curbing the growth in fees at universities.

The #FeesMustFall protest of 2015 began as a protest by students against fee increases at institutions across the country.

Speaking at the second day of a three-day higher education conference organised by Universities South Africa (USAf) — a membership organisation representing South Africa’s universities — in Pretoria on Thursday, Diane Parker, the deputy director general (responsible for university education) at the education department, said developing the regulatory framework was no easy task and that the task team is approaching it in a very objective manner.

“We are working towards a regulatory framework, we know we have to. We don’t have a choice. The context has overtaken us. We are in the process of doing data collection and analysis and it is going to take us longer than we thought,” she said.

Professor Adam Habib, Wits University’s vice-chancellor, who is part of the task team told the Mail & Guardian on the sidelines of the conference that the team has asked all universities for more information. This includes: their student debt, how much their fees are, how much of their money goes into education, how they are spending their money and how much money they make from endowment.

Habib said this information is crucial, as the task team needs to first understand how institutions work out what they will charge.

In her presentation, Parker provided data that shows the average full cost of study at all the universities. She said this came from 2019 preliminary data collected from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme, and how much the scheme is paying for a full cost of study for students across institutions.

The top five institutions, out of the 26, that rank high in terms of full cost of study according to the data are: University of Cape Town at R148 159, Stellenbosch University at R127 621, University of Pretoria at R113 593, Wits at R111 562 and Rhodes University at R106 429. While the top five universities that rank low in their full cost of study are: University of Limpopo at R67 425, Vaal University of Technology at R54 502, Central University of Technology at R54 402, Durban University of Technology at R53 161 and Unisa at R14 833.

Parker said the data showed that there was a huge difference in student fees amongst institutions. She, however, said some of the costs have to do with how universities operate, the types of facilities they have and that some of the facilities might be expensive to maintain.

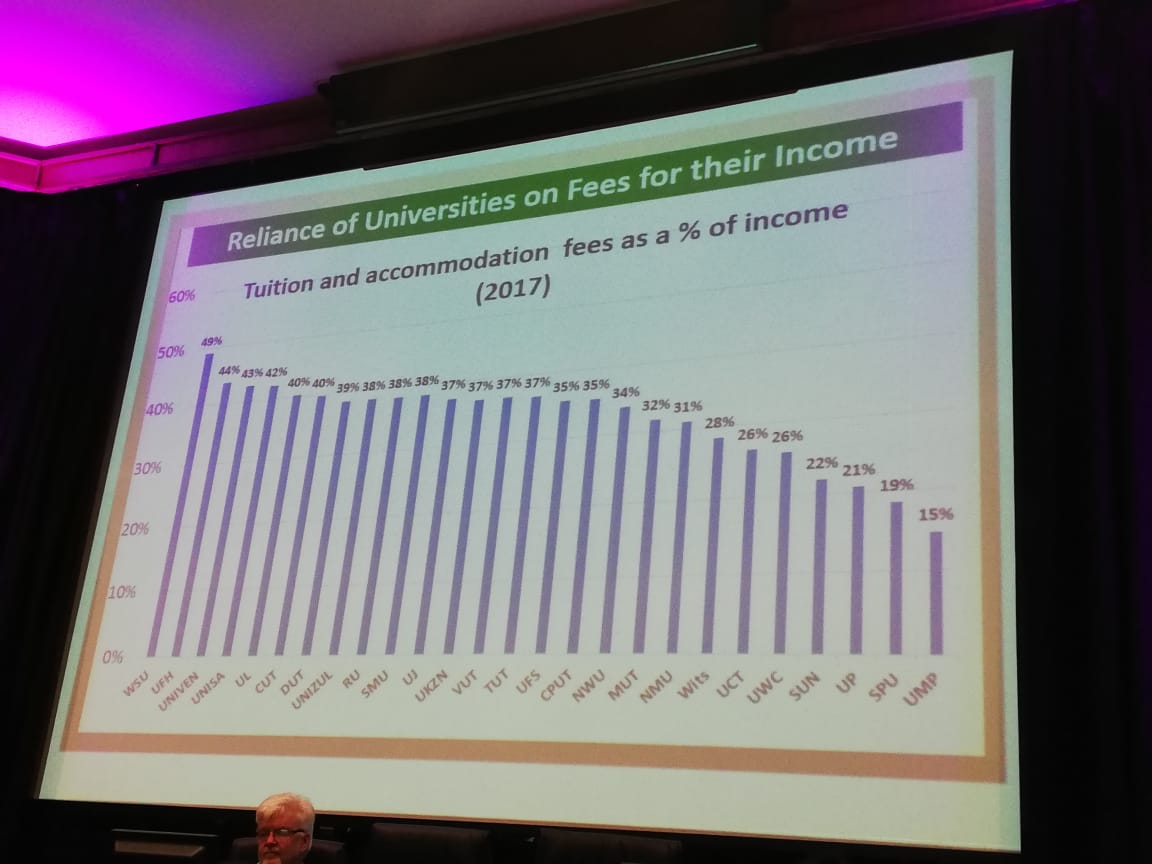

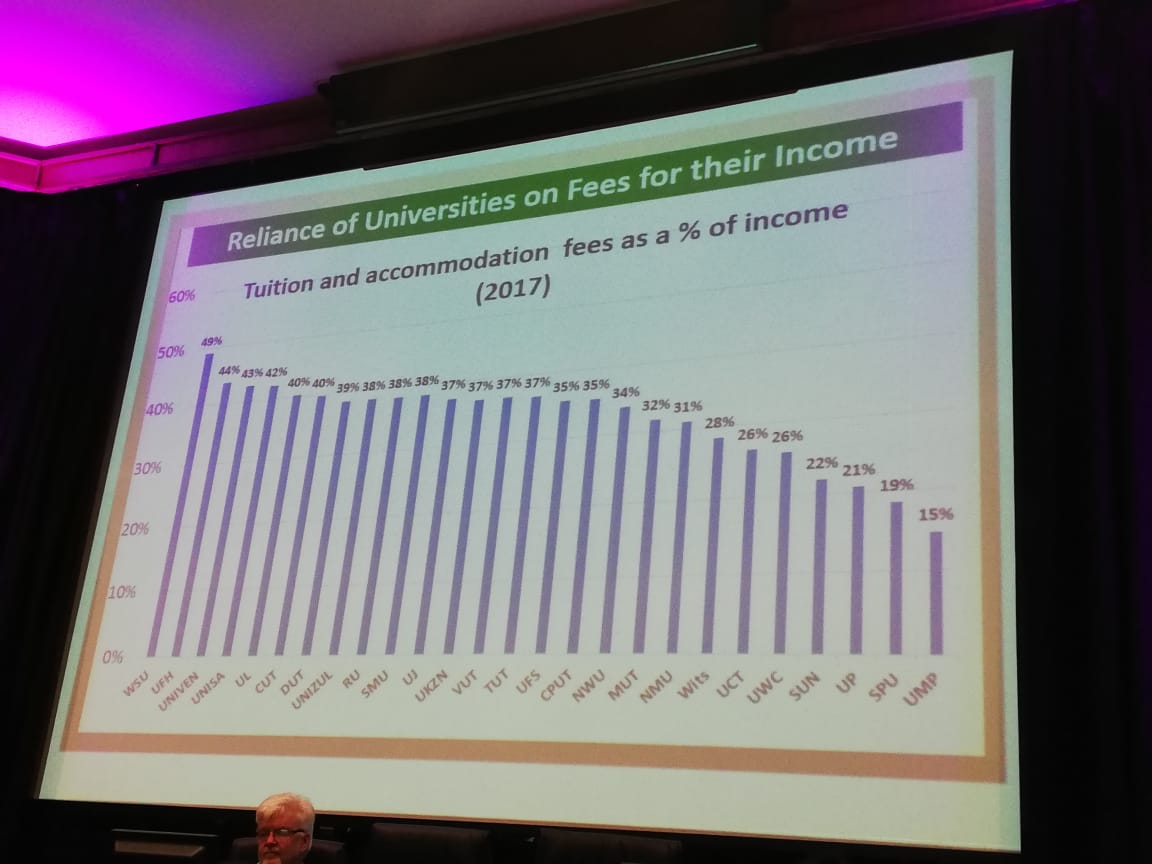

She also presented data that showed the universities that are most reliant on university fees for their income, but the data used was from 2017.

The top five universities that heavily relied on student fees were: Walter Sisulu University (WSU) at 49%, University of Fort Hare at 44%, University of Venda at 43%, Unisa at 42% and University of Limpopo at 40%.

(Bongekile Macupe/M&G)

(Bongekile Macupe/M&G)

The institutions that rely the least on students fees are University of Mpumalanga at 15%, University of Western Cape (UWC) at 26%, Stellenbosch University at 22%, University of Pretoria at 21% and Sol Plaatje University at 19%.

(Bongekile Macupe/M&G)

(Bongekile Macupe/M&G)

Vice-chancellors who spoke to the M&G said regulating fees is needed in the sector — but only if it is done fairly.

Professor Tyrone Pretorious, the UWC vice-chancellor, said the sector agrees that there needs to be a national framework that will guide institutions on how to set their fees, but this cannot take over the role of council ( the highest decision making body) who are responsible for setting fees. As a starting point, Pretorious said, it would be “foolish” to suddenly raise the fees of the low paying institutions to that of the high paying fees or decrease that of high paying to low paying fees especially in the current economy of the country.

“There is confusion and some people believe that we are going to have the exact fees set a national level for example that all BA degrees will be R60 000, that is not what it means. What could be a possible mechanism is that they will be a set of guidelines that says, for example, the low fee paying institutions should have an annual increase of 2% above inflation while the high paying institutions should either have an inflation related increase … What that would do, in time, is that it would narrow the gap between the high fees and the low fee [paying institutions],” he said.

Habib said a fee regulation task team has to consider that institutions have different mandates.

“If you are a research intensive institutions, produce masters and PhDs and producing research your cost structure is going to be very different from somebody who is teaching undergraduate students. How do you cater for that?” he asked.

WSU vice-chancellor, Professor Rob Midgley, said the first limitation in charging fees is that students are agitating for a no fee regime, and do not want to entertain any talk of fee increases.

“There is quite a strong political pressure either to have no fees or no fee increases in the process, so that kind of thinking puts a lot of pressure on us because we are so reliant on fees,” Midgley explained.

He said when increasing fees students also question where the money goes to because they have poor living conditions, the laboratories are not state of the art like other institutions and students find it unfair to pay more fees when they are not seeing a difference in their own lives.

“Those are the constraints that we have, but the bottom line is if we have to have fees, we have to have fee increase because if we don’t increase at least by inflation it means in real terms we are going to give them poor services next year than this year because everything goes up and we are only going to be able to pay for less, so this is something that must happen.”

Parker said the draft regulatory framework will be published for public comment next year in March, and that the final policy will be published in September 2021.