(John McCann/ M&G)

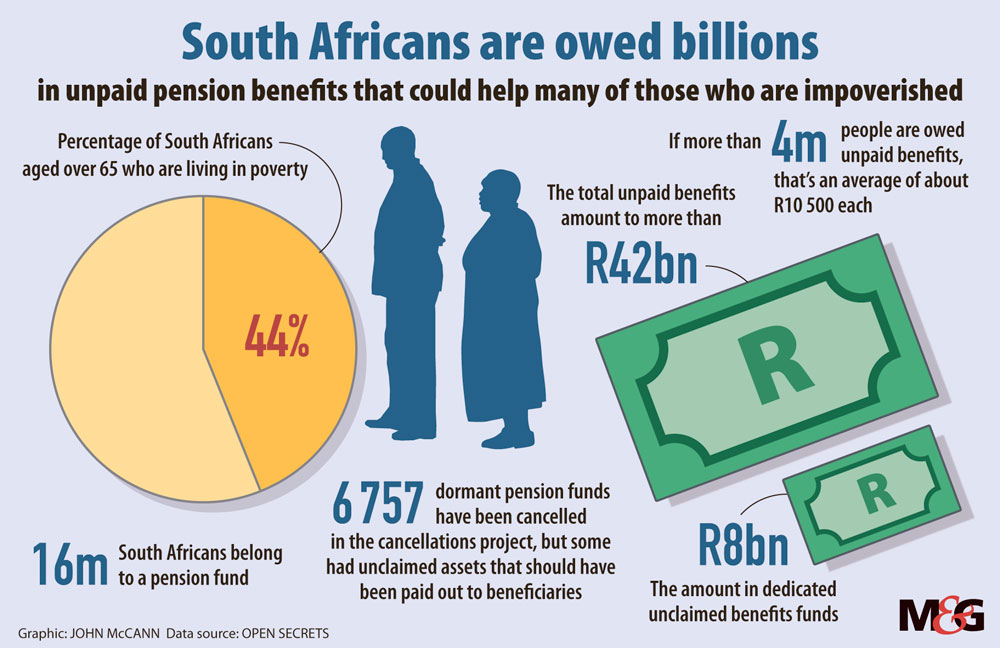

Pension fund industry players continue to profit from the R42-billion owed to the four million South Africans still waiting to be paid their pensions.

This is according to a recently released report by non-profit organisation Open Secrets. The Bottom Line is the culmination of a year-long investigation into South Africa’s pension fund industry.

The report contends that the industry has been structured to benefit corporations, leaving pensioners — who every month of their working lives give up a portion of their earnings to secure a dignified retirement — out in the cold.

The fight over unpaid pensions was sparked when former deputy registrar of pension funds Rosemary Hunter identified significant problems and likely unlawfulness in the Financial Services Board’s mass deregistration of so-called “orphan funds”. These are shell funds left without any members or assets, or dormant funds without boards.

In July 2014, Hunter filed a whistle-blowing report to the board of the Financial Services Board, now the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA). This alleged that there had been a mishandling of the deregistration process, which saw the cancellation of thousands of funds, without — Hunter said — proper oversight.

Last year, Hunter lost a Constitutional Court bid to compel the Financial Services Board to investigate all the funds that were deregistered in the cancellations project.

The Open Secrets investigation found that between 2007 and 2013, up to 6 757 pension funds were deregistered by the pensions’ regulator at the behest of private fund administrators such as Liberty and Alexander Forbes.

This occurred despite the fact that some of these funds still held assets and people were owed payments from them, the report claims.

“For their part, administrators like Liberty and Alexander Forbes used the project to rid themselves of responsibility for thousands of dormant funds, while sometimes holding on to their assets,” the report reads.

The assets of cancelled funds were often moved into unclaimed benefits funds held by the fund administrator. Since 2008, the assets of these funds have increased from R450-million to over R8-billion.

The report notes that almost all of these funds have been set up and are administered by large private financial service providers, “who may derive significant financial benefits from both fund administration fees and also asset management fees levied by asset managers”.

Another whistle-blower, Michelle Mitchley spoke out about the process for cancelling pension funds administered by her then employer, Liberty.

Mitchley claimed in an affidavit to the Constitutional Court that the company had “contracted service providers who were financially incentivised to achieve the cancellation of as many funds as possible within the shortest possible time”.

By August 2018, Liberty had admitted to irregularly cancelling 130 pension funds with about R100-million in assets that were owed to 3 000 beneficiaries that needed to be reinstated in order for payments to be made.

The Open Secrets investigation looks at what may motivate financial services providers to aggressively cancel pension funds.

According to the report, Liberty and other fund administrators profit from fees that are directly linked to the extent of assets under their management.

The report reads: “As a result, their employees have an interest, if not a duty, to increase or at least maintain their employer’s assets and profits. For these purposes, what could be better than billions of rands sitting in pension funds that are unlikely to be paid out to beneficiaries but could remain a source of income to the company in perpetuity?”

The report calls the cancelled pensions funds saga a “cautionary tale”.

“This is a story of soft touch — or out of touch — regulation whereby the interests of corporations were put ahead of those of pensioners.”

The report thus calls for a “move towards a framework that genuinely protects the most vulnerable from ever-more-powerful financial institutions”.

According to the report, well over 16-million South Africans today belong to a pension fund. Of these, about 90% are members of over 5 000 privately administered pension funds, most of which are run by some of South Africa’s largest financial institutions. These pension funds hold assets of over R4-trillion. With this amount at stake, “the need for sweeping reform is urgent”, the report reads.

In response to questions from the Mail & Guardian, Liberty denied profiting from the cancellations project.

Liberty chief executive Tiaan Kotze said Liberty employees and service providers were incentivised to effectively complete the deregistration project and that the firm had internal controls to validate the quality control of the submissions.

“However, due to the complex history of acquisitions and migrations of systems and data across multiple administration books, certain asset records were delinked from the administration records. This resulted in certain funds being deregistered in error by Liberty and some of the previous administrators.”

Kotze added: “We are fully committed to paying the benefits to members of these funds.”

Alexander Forbes said the firm has noted the report and reiterated that, where it administers unclaimed benefits, “we make every effort to determine if we have a benefit for a potential claimant”.