R-E-S-P-E-C-T: The NGO Action Breaks Silence runs the Hero

From “sinister sexual behaviours” to “lies” and efforts to “manufacture ignorance”, Joan van Dyk looks at the high-stakes fight to decide what students are taught about their bodies and about sex.

Thirteen-year old Nadine is annoyed.

“You’ve known me, like, forever,” she says. “You know I don’t have diseases.”

“You’re totally hot,” Zubair replies. “But this arguing over the condom — it’s ruining the mood.”

Nadine, starts to undress her boyfriend and responds: “I’ll get you back in the mood”

This is not a scene from a coming of age romance movie. It’s a script from the department of basic education’s new sex-ed lesson plans for grade eight school children. The new curriculum is aimed at moving the country beyond the ABCs — abstain, be faithful, condomise — and towards comprehensive sexual education for school children from grade four to matric.

This kind of sex-ed teaches children about the emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality.

Classroom content can feature everything from information about contraception to role playing how to handle scenarios involving bullying, sexting and even — like the scene between Nadine and Zubair — relationship power dynamics.

Ideally, says the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, comprehensive sex education leaves learners empowered to make decisions about their health and understand how their choices affect others.

The approach has been scientifically proven to help children make safer sexual choices.

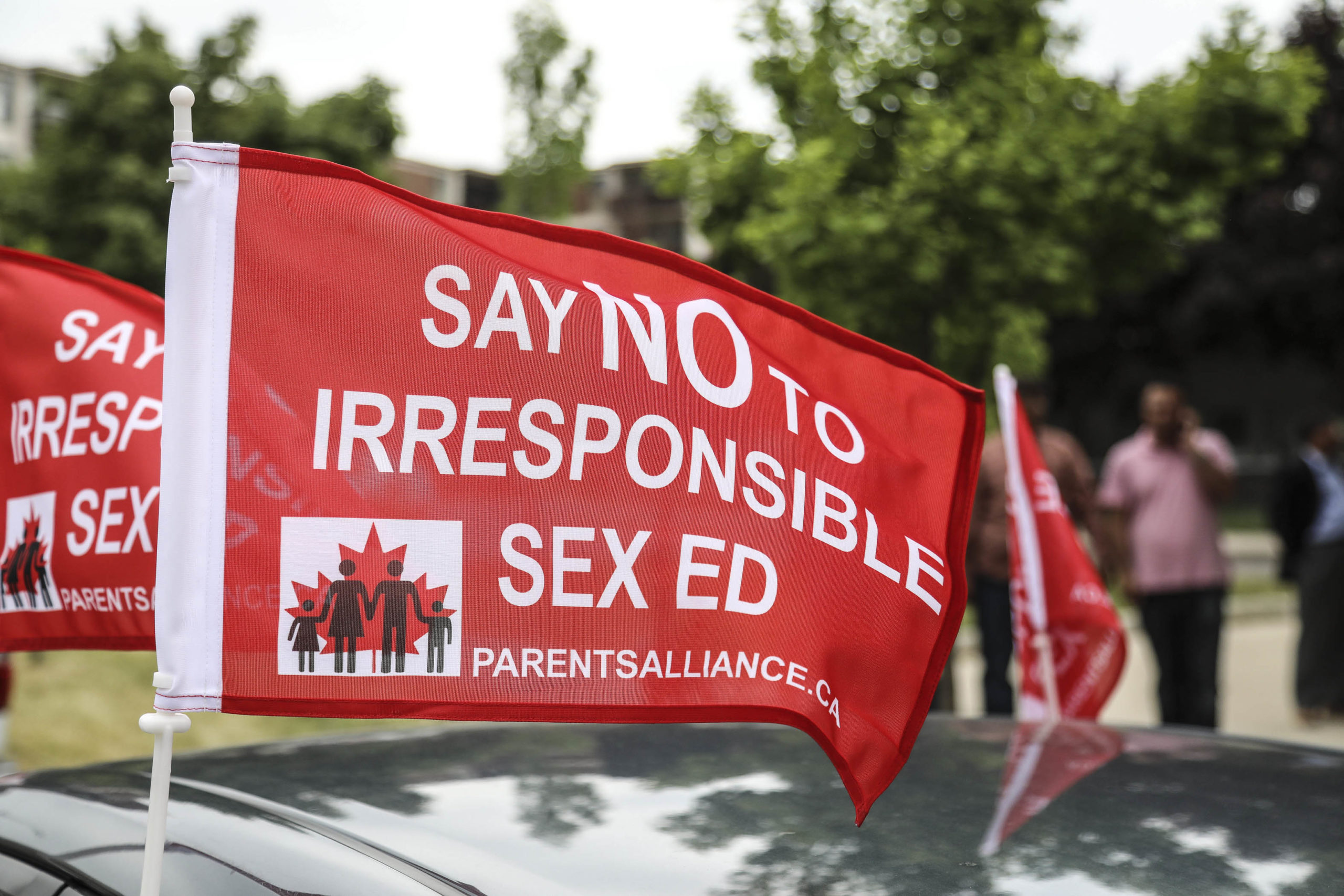

But, in South Africa, the education department’s new plans to teach this way have provoked a backlash among some parents, religious groups and teachers’ unions. These groups are pushing unfounded claims that giving children information about sex will encourage them to experiment with what the Christian think tank, the Family Policy Institute, calls “sinister sexual behaviours”.

Meanwhile, researchers disagree about whether the plans are progressive at all.

The Life Orientation curriculum in South Africa is totally disconnected from young people’s lives, argues Catriona Macleod, a professor of psychology at Rhodes University in Makhanda.

In 2015, Macleod and her colleagues asked 24 Eastern Cape college-age students what they thought of the sex education they got in school as part of a study published in the journal Perspectives in Education.

Students mostly scoffed at their teachers attempts to teach them the ABCs, which go one step further than abstinence-only education by teaching learners that if they do choose to have sex, they should only have one partner, and that they should use a condom.

But young people said lessons where teachers tried to “preach” to them about how they should behave had little bearing on their conduct outside of class.

One student explained: “We write tests, we study the best ways to abstain. We know it’s in our minds, but we don’t do it outside [of school].”

Nationally, the number of teen moms delivering in hospital fell by 11% between 2012 and 2017, district health data published by the Health Systems Trust reveals. But that still translates to just under 23 000 of the almost 1-million babies delivered in 2017 being born to mothers between the ages of 10 and 19, Statistics South Africa recorded.

Almost three out of every four girls who had children before the age of 18 said their pregnancies were unintended, according to a 2012 South African household survey published in the journal African Health Sciences. About half said they didn’t understand how conception worked at the time they fell pregnant.

Today, women between the ages of 15 and 24 make up a third of the country’s new HIV infections, preliminary results from the country’s HIV household survey shows. Less than half of women in this age group reported using a condom the last time they had sex.

In a 2014 systematic review published in the journal PLoS One, researchers pitted the three models of sex education against each other. That is, abstinence-only, the ABCs and comprehensive sexuality education.

The winner? Comprehensive sexuality education.

This had the largest impact on changing HIV-related behaviours such as early sexual debut, condom use and fewer sexual partners, researchers found.

The most effective sexual education interventions were those that also included activities outside of school, such as training healthcare staff to offer youth-friendly services, distributing condoms and involving parents and communities in the development of the lessons.

South Africa’s national action plan to fight HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections includes a goal to roll out comprehensive sexuality education. In the next two years, the government aims to have this type of sexuality education in half of all schools in areas that have a high burden of HIV.

But at the moment, only 5% of schools teach comprehensive sexuality education, the document shows.

Comprehensive sexuality education, Rhodes psychology professor Catriona Macleod says, is a far more effective way of reducing teen pregnancies and new HIV infections than its competitors.Macleod explains: “Whatever your moral position is, if you look at the research comprehensive sexuality education is the way to go.”

“Dear diary, I saw an angel. She looked like heaven on earth; every boy’s dream.”

That’s what one 16-year-old boy wrote in his journal as part of a 2003 study. But what he and other young men were confiding to their diaries as part of the research was very different than what they were saying in group discussions with other boys. This is according to the paper — published as a result of this study in the African Journal of Aids Research — which looked at HIV education in six African countries including South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

In group interviews with peers, young men bragged about sleeping with girls and then dumping them — a phenomenon researchers chalked up to harmful messages children get about what it means to be a man.

If it weren’t for the diary entries, researchers would never have known about the heart wrenching stories of love and loss that young boys experienced.

The department’s new plans address this with multiple lessons that teach children how to identify unhealthy stereotypes about men and women – and explains what they could do instead. For example, the plans explain: “You get to decide how you want to be a man.”

Macleod, however, is not convinced the department’s plans go far enough to move beyond messages of danger and disease around sex. She points to the words printed in bold black letters at the start of the section about harmful gender stereotypes — “The SAFEST choice is abstinence.”

“Same-old, same-old,” she quips. “They’re still pushing abstinence as the main goal.”

In addition, the plans don’t do enough — according to Macleod — to integrate the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender children.

But Anthony Brown disagrees. He’s a senior life orientation and inclusive education lecturer at the University of Johannesburg’s department of educational psychology.

He believes the plans will open up discussion and understanding about all sexual identities.

Most examples in the documents, however, focus on heterosexual couples.

While the plans do include lessons about children’s rights to expressing their sexual identities and to choose whether they want to be sexual, Macleod argues they do not give learners the tools to advocate for their own sexual and reproductive health rights.

She argues that instead of just teaching children about contraception, for example, they should learn about their right to birth control and why it’s difficult for many South Africans to get contraception in the face of frequent public sector stockouts.

Macleod explains: “There is no analysis on the systemic inequities that shape people’s lives. You cannot talk about sexual and reproductive justice without looking at the circumstances that mean some people are reproductively healthy and others not.

Also missing from the plan is any mention of the legal right of anyone regardless of age to obtain a safe and legal abortion in South Africa. By law, minors wishing to terminate a pregnancy do not need a parent’s consent.

But Elijah Mhlanga, the spokesperson for the department of basic education, is adamant his department’s plans are age-appropriate and rights-based.

He argues: “Abstinence is only one of the choices presented to learners. The materials are inclusive and do not favour any orientation.”

“Parents are being lied to,” reads a call to action on the website of the Christian think tank, the Family Policy Institute. The campaign links to a petition hosted by educational consulting nonprofit Family Watch International titled “Stop CSE” or comprehensive sexual education, which the institute says is part of a “deceptive agenda” by UN agencies that constitutes a “war on children”.

The institute is one of a growing choir of dissenting voices — including the South African Teachers Union (SAOU) — that have taken a stance against the government’s new sexuality education programme.

Despite overwhelming peer-reviewed evidence to the contrary, Errol Naidoo, the institute’s founder and chief executive officer, says comprehensive sexual education promotes dangerous sexual behaviours and “sexually indoctrinates people’s children” with messages he calls “LGBTI propaganda”.

Asked to comment on the scientific evidence that supports comprehensive sexual education, Naidoo responded: “It’s a lie.”

Naidoo can’t produce any peer-reviewed evidence to support his claims about the dangers of the department’s plans. Naidoo instead referred Bhekisisa to a research review conducted by pro-abstinence organisation, the Institute for Research and Evaluation.

The policy brief examines studies used by the United Nations, and how effective comprehensive sexuality education is influencing condom use, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections and whether the lessons were linked to students starting to have sex. It found comprehensive sex education has a higher failure rate than abstinence-only education.

The researchers however counted the results from ABC programmes under comprehensive sexual education.

University of the Witwatersrand researcher Haley McEwen says the petition Naidoo’s organisation links to is part of a broader attempt to “manufacture ignorance”. She says this type of misinformation is part of an international trend funded by US groups such as Family Watch International. Family Watch has launched similar petitions against comprehensive sexuality education in other African countries including Kenya.

“There’s a real effort to generate knowledge that can back some of their claims,” she says.

The president of the SAOU teacher’s union, Chris Klopper, also referred to the Institute for Research and Evaluation’ research review as evidence against comprehensive sexuality education. He says the union takes issue with what he refers to as explicit images used in the plans — for example, an illustration of a gonorrhea-infected penis included in matric lessons about sexually transmitted infections.

Teachers’ motivation — and attitudes — towards sex-ed are critical to the success of programmes, research and history have shown. For example, a 2015 study published in the journal Sex Education documented lessons learned when 11 low-income countries in Africa and Asia piloted an online comprehensive sexuality education programme.

The work found that teachers who felt comfortable talking about sex and who were motivated to teach tolerant attitudes towards sexuality were more likely to relay programme messages. Educators who weren’t were likely to gravitate back towards teaching lessons about abstinence.

Education researcher and life orientation specialist Anthony Brown agrees training will be critical in the success of South Africa’s latest programme — including whether or not they are counselled on how to deal with the subject of child sexual abuse.

The 2016 Optimus Study conducted by the University of Cape Town found that one in three South African children will have experienced some form of sexual abuse by the age of 17 although this figure also includes consensual sex between 17- and 18-year-olds, which is legal in South Africa.

Teachers will need to be equipped to handle situations in which students might learn they are being abused during class time.

Brown remembers an example from his work with Life Orientation teachers, in which a child was told to write an essay about her culture. She wrote at length about her stepfather, who she says would come into her room every night and sleep with her to “teach her how to be a good wife to her future husband”.

Under South African law, teachers must report any suspected child abuse to a social worker, the police or the department of social development. Brown says educators need to know how this works in practice.

He explains: “These lessons could open up a world for people they might never have been aware of. Teachers need to be ready for that.”

Back in the realm of teenage desire, Zubair is standing his ground. “This has to stop,” he says. “I’m not doing this without a condom.”

“What’s wrong with you?” comes Nadine’s retort, presumably rolling her eyes.

“Nothing,” he says. “I’m looking out for us — I think I’d better go home.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Subscribe to the newsletter.