(John McCann/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

Without numbers, you cannot run a country. This is how the former statistician-general of Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), Pali Lehohla, views the country’s prospects if the organisation cannot be adequately funded.

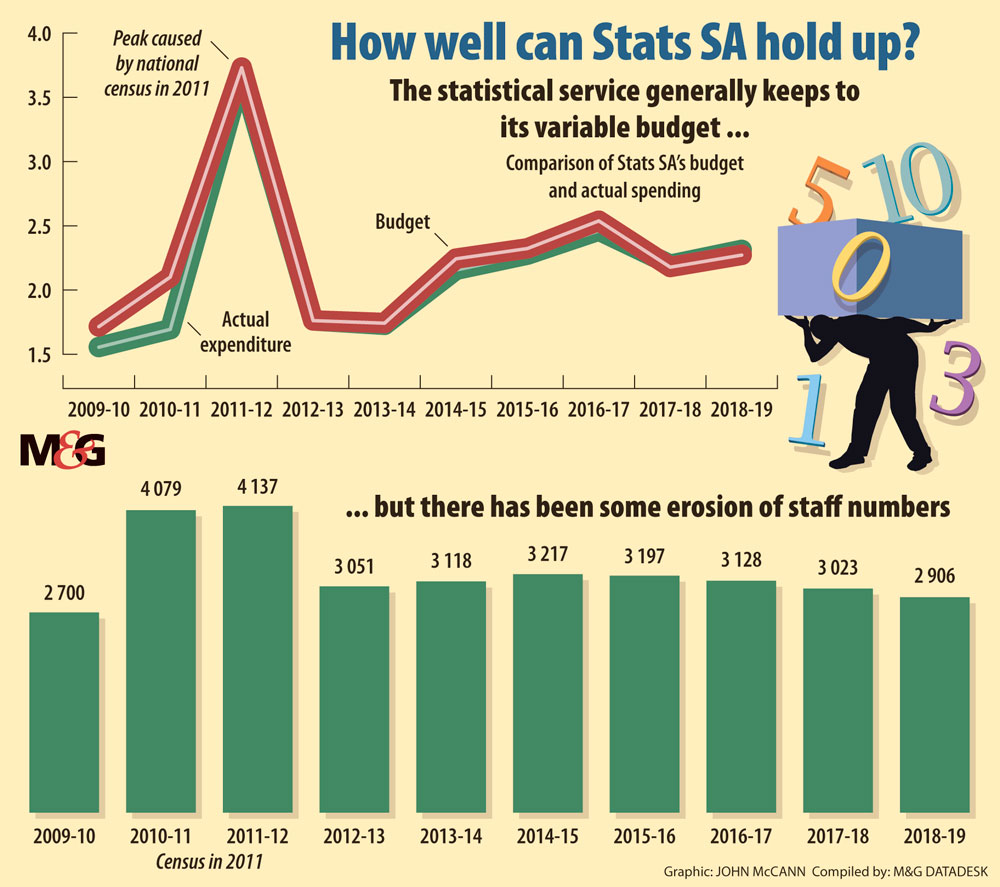

Stats SA is in the midst of its worst financial crisis to date — and not because money has been squandered over the years, or because officials have been corrupt. Rather, the government has been tightening the proverbial belt, cutting the funding given to Stats SA. The council that endorses the country’s statistics has had enough and last week gave the government an ultimatum — give the statutory body the money it needs (about R200-million) or the skilled statisticians that help make the organisation world class will leave.

For years, Stats SA has stated that resource constraints are causing various challenges, including stopping value-added activities staff being overworked. As a result, more errors were being detected and there was a steady brain drain without the positions being refilled.

The threat is not idle and the players know what is at stake. During an interview with the Mail & Guardian, Risenga Maluleke, the current statistician general, said that Minister in the Presidency Jackson Mthembu agrees that there will be serious problems if the funding squeeze continues.

According to Professor David Everatt, chairperson of the South African Statistics Council, if the government will not provide the funding needed to fill posts with skilled people, keep sample sizes up, and innovate, the council will be forced to withdraw its support for official statistics.

“This is the very worst option for everyone in South Africa — but council either endorses the release of data everyone can trust, or council stops because we cannot endorse data we mistrust,” he said in a statement.

Former statistician general Lehohla knows the consequences of producing statistics with a considerably reduced budget. He told the M&G that back in 2003, a few years into his tenure, Stats SA was experiencing budget cuts and this had a direct effect on the quality of statistics produced — and the pockets of many pensioners.

“Within the first two years of my tenure, I messed up big time. And one of those was the consumer price index. In good part, it wasn’t my fault but the buck stops with me. Treasury refused to provide us with R6-million … then we had to do whatever we had to do to estimate the consumer price index,” he said.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Lehohla said that when he messed up it made a lot of people suffer, especially pensioners.

“They had bought options against inflation-weighted bonds. Our inflation numbers were incorrect and when we corrected this and the inflation went down, they lost. This was a very painful mistake. There are very expensive consequences when there are mistakes because of finance. Without finance, Stats SA will break,” he said.

Stats SA publishes about 263 reports every year. This equates to at least one release every working day. These reports inform the government and citizens of how many people are eligible to vote, how many bucket toilets still exist, what is the housing backlog, the consumer price index and unemployment rates, to mention a few.

Through the census, which is the biggest undertaking by the organisation, Stats SA must map out the entire country by collecting information from all households. As Stats SA notes on its website: “For many people, the census may be the only time that the state reaches them and asks them a question.”

This is vital work. Lehohla said without a Stats SA the country might look very much like it did under the apartheid dispensation, when people were not visible and hidden in spaces such as the homelands. Those are toxic environments.

“The architecture of our democracy rests on these numbers,” he added.

Data contained in the census is used to ensure government funds and services are distributed fairly, to delineate electoral districts and to measure the effects of industrial development. The census also provides the benchmark for all surveys conducted by the national statistical office. So, for instance, without the data contained in the census it would be difficult to determine the country’s unemployment rate.

Another vital count is of those who are unemployed which is a large portion of the country. Stats SA tracks unemployment through its quarterly labour-force survey, which collects data on the labour market activities of people aged 15 years and older. This data is the main indicator of the country’s deepening unemployment crisis, which according to Stats SA, soared to an 11-year high in the third quarter of 2019, with an unemployment rate of 29.1%.

The poverty statistics are essential to monitoring the objectives of the National Development Plan, which is the backbone of the government’s plan to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030.

The last living conditions survey, released in 2015, found that about half (49.2%) of the adult population were living below the upper-bound poverty line. But due to the budget cuts at the statistics agency, there are no recent numbers to see how the situation has deteriorated.

According to Maluleke, the treasury has provided Stats SA with some emergency funds to undertake this work, but it might not be enough because of the amount of resources that go into collecting this kind of information. “You need field workers who you must hire. You need vehicles that must reach out to these people. You need communication in the form of telephones. You need to train these field workers,” he said.

But instead, Stats SA has not been able to hire anyone, apart from the statistician general, since as far back as October 2016.

Everatt said he finds it difficult to understand why a respected, reliable and important institution — that plays by the rules and is praised by the auditor general — is, in effect, punished by the government by being financially squeezed, “while those deeply implicated in state capture receive bail-outs of massive proportions”.