Changing laws: Hendri Terblanche is petitioning MPs to legislate elder-care leave. (David Harrison/M&G)

‘When you are a child, your parents do everything in their abilities to take care of you. They go out of their way to assist you and they make a lot of sacrifices. And now it is important that we look after our parents to the best of our abilities,” Cape Town Democratic Alliance city councillor Hendri Terblanche says over the phone.

Terblanche has petitioned Parliament for an amendment to South Africa’s labour legislation that would allow workers to take paid time off to look after their elderly parents and grandparents.

He is soft-spoken. It’s a strain to hear his voice in the crackly recording of his address to Parliament’s portfolio committee for employment and labour last week.

Terblanche, who successfully petitioned Parliament to amend legislation to provide for paternity leave, says he took on this more recent task after his mother-in-law was diagnosed with cancer.

He says although many people have considerate bosses who give their workers time off to take care of their families, others do not.

It’s not a “radical change” he is asking for: “It is just broadening the definition of ‘family responsibility leave’ by putting in five words.”

Currently the Basic Conditions of Employment Act provides for leave to be taken when a worker’s child is sick. Terblanche wants the words “parent, adoptive parent or grandparent” added to this definition.

“The Act will then be in line with the Constitution,” he says.

Terblanche adds: “Family responsibility leave was designed for taking your role as a caregiver, but not as receiving care. And like with all legislation, what is applicable today might not be applicable tomorrow … Your parents won’t tell you: ‘Oh, I am not feeling well.’ They will always put on that brave face. Because their first instinct is to look after you.”

South Africa’s ageing population necessitates the change, Terblanche notes. According to Statistics South Africa’s last census, in 2001, people over the age of 65 accounted for 4.9% of the population. By 2016 they accounted for 5.3%. Between 2001 and 2016 the ageing index — which reflects the proportion of older people to children — rose from 23 to 27.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

A legal opinion by the Centre for Constitutional Rights, a unit of the FW de Klerk Foundation, notes that because of economic constraints and the rise in the cost of care, very few people have the luxury of securing professional care for their older family members; instead, they rely on assistance from relatives. As a result, older people often retire to the homes of their adult children, the legal opinion reads.

The centre points to three countries — the United States, Japan and Australia — that have introduced some form of elder-care leave.

In the US, which notoriously does not provide for parental leave, the Eldercare and the Family Medical Leave Act allows workers to take up to 12 weeks each year of unpaid leave to care for ill family members, including elderly parents.

In Japan, workers who make contributions to the government’s unemployment insurance scheme can earn up to 40% of their wage while on family care leave. This long-term leave can be taken for up to 93 days. And in Australia, workers are entitled to 10 days of paid leave when a member of their immediate family requires care due to illness or injury.

No African country has signed elder-care leave into law. But caring for older people is enshrined in protocol adopted by the African Union. Article 10 of the Protocol on the Rights of Older Persons in Africa enjoins member states to adopt policies and legislation that provide incentives to family members who provide home care for older people. However, only five of the 55 AU member states have signed the protocol and none have ratified it.

Some countries have taken other steps towards providing added support to their ageing populations.

In 2010, Ghana implemented its National Ageing Policy, which acknowledges the country’s failure to meet the needs of older people. The policy is aimed at improving healthcare, housing and income security.

China, where by the end of 2018 people older than 60 accounted for 17.9% of the population, has identified the lack of a safety net to protect older people as a threat to its economy. The country’s policymakers have intervened to ensure that the weight of caring for an ageing population will not stymie its development. In 2019, China’s state council issued its national plan to cope with an ageing population. One of the tasks set out in the plan is to build a social environment conducive to supporting older people.

Terblanche says the introduction of elder-care leave into South Africa’s labour legislation will make the country a better place. “It will bring back the care-giving side of us … It will bring back the key relationship that will strengthen families.”

He says now is the perfect time for this change. “We live in a society in which people don’t even communicate with each other. People sit next to each other in a restaurant and they are busy on their cellphones.”

“So, now, if this gets implemented you will be in a better position to take better care of others. So it’s not about taking care of yourself; it’s about caring for others.”

How to take parental leave

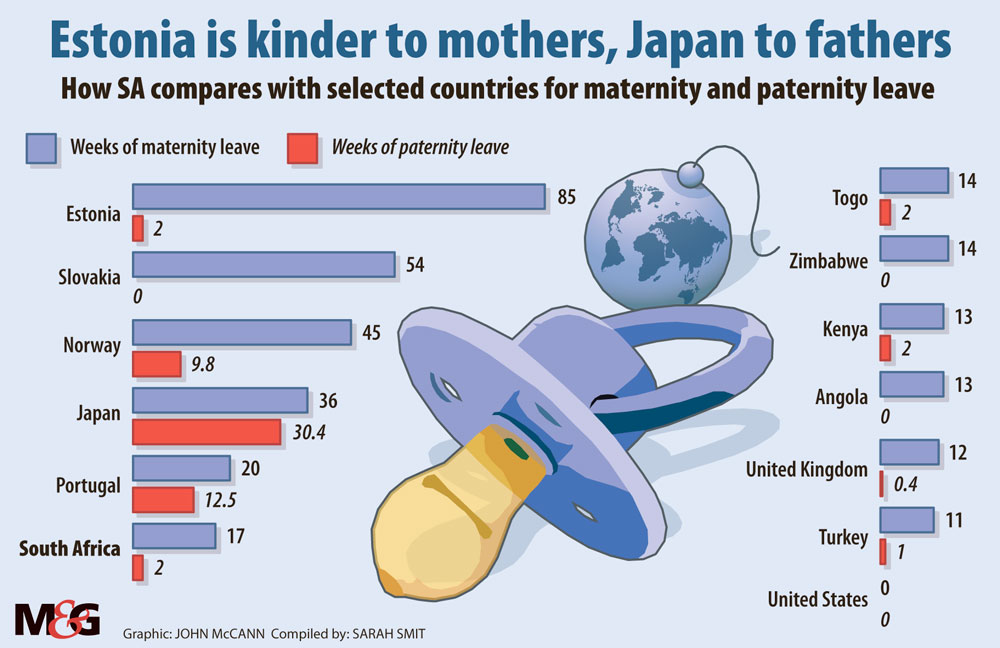

In South Africa, parental leave is unpaid, but an employer is obliged to hold the worker’s job open until they return. Maternity leave in its current form has been law for more than two decades.

But the country’s new parental leave laws — which include fathers, adoptive parents and surrogates — were signed into law only in January.

Working parents can draw from their contributions to the Unemployment Insurance Fund to cover their leave. To apply for leave, expectant parents must go to a labour centre and hand in a number of documents, including IDs, details of a valid bank account, a medical or birth certificate, and the application forms.