Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu perform at the Market Theatre Cafe in 1977. (David Marks / Hidden Years Music Archive Project)

In the late 1970s, Dax Butler remained on The Market Theatre Café’s stage between sets while the rest of his band, called The Other Band, went outside for a joint. He played a song he had been working on that commented on the repressive apartheid state — “Hygiene’s ancient capers/ Wipe my ass with your newspapers/ A battery of flattery and lies/ Just about the size of the headlines/ If you’re looking for Godot/ Go on down to Soweto he’s waiting there” — forgetting that club owner David Marks was recording the whole set.

The Market Café was, much like its owner, as visionary as it was eccentric. Malcolm Purkey, a former director of The Market Theatre, says the venue was filled with chairs of every description — including a dentist chair — and “would never have passed the safety standards that venues have to today”. It was a place where sound people could experiment with new systems, budding artists were nurtured, institutions, productions and careers were launched, and audiences could hear performers such as Malombo and Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim) before they became famous.

Singer/songwriter Dax Butler is still going strong 40 years after he performed at the Market Theatre Cafe (Jonathon Rees)

Singer/songwriter Dax Butler is still going strong 40 years after he performed at the Market Theatre Cafe (Jonathon Rees)

Butler wasn’t a protest artist as such, but staying quiet about what was going on in South Africa at that time was difficult for any artist with a conscience. “The mood was completely different after the ’76 Soweto uprising,” he says.

Marks had a habit of recording “anything that moved or murmured”, so it’s likely that Butler’s song is somewhere in the Hidden Years Music Archive Project. This a vast collection of music, films, notebooks and photographs is now being ordered and archived in a mammoth undertaking – its 175 000 items weigh more than seven tonnes – by Lizabé Lambrechts and her team at the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation at Stellenbosch University.

A musician himself, Marks had a couple of hit songs in the late 1960s, most notably Master Jack, which helped to further his passion for recording, filming and providing platforms for South African musicians. The aim of his record company, 3rd Ear Music, was, according to its website, “to promote, produce, protect and publish local acts deemed non-commercial or too political”. A musician who helps other musicians, he’s not unique (think Ry Cooder and the Buena Vista Social Club) but in apartheid South Africa, it was pretty much only musicians that kept the indie side of music alive.

The country was at this stage, as Master Jack describes it, “a very strange world”, where even listening to “different” music, let alone playing it, could land one in trouble. To get an idea of the oddness, hippies at a rock festival were held down by Afrikaans divinity students and had their locks shaved off in South Africa’s very own Homer Lee Hunnicutt moment in what became known as The 1970 Kruger Day Hair Massacre.

Recording blues

To get a song or an album recorded in the 1970s and 1980s was no mean feat. “Remember that back then recording wasn’t as easy as it is today; it was expensive and restricted,” says Deon Maas, who worked for Tusk and was a label manager for One World Entertainment. Back then musicians were at the mercy of commercial record companies. These companies seldom spent time and money developing local artists, preferring instead to promote international music, which they believed was more likely to yield profits on their investments.

Local singers who opposed the apartheid were unlikely to be promoted, but Ian Osrin, a former producer for Teal-Trutone, says if an artist had a protest message, it could be disguised in townships codes. For example, Love Target by Zashaa was based on township residents chanting “Targeti, targeti” as they stoned passing police cars, and “the Teal executives were totally in the dark about” its hidden message. Maas said record companies minimised the chance of getting songs banned “by not printing the lyrics, or printing them very small, or in a difficult-to-read manner”.

Some musical genres were selling well, such as that of Gé Korsten, an opera tenor and actor who later sang lighter songs in Afrikaans. Kwela, mbaqanga and isicathamiya (and later, hip-hop, kwaito and rap) were huge. Marks says: “Black musicians were producing and selling records by the hundreds of thousands. The township and rural events that I was involved with — from the late Sixties to mid-1980s — were massive. Black record producers were swanning around in Jaguars with bodyguards and bling.”

But many black artists were ignorant of copyright law and were exploited by record companies. They were paid in once-off session fees or even, as maskande musician Philemon Zulu said, taken to a general dealer and told to fill a wheelbarrow with whatever they could find in lieu of cash. The biggest rip-off of all was that of Solomon Linda, whose song Mbube (later known as Wimoweh and When the Lion Sleeps) generated millions, of which Linda and his family got a mere pittance.

Western music flooded the South African market, and the big money went into paying local session musicians to cover foreign chart-toppers, perhaps most famously on the Springbok Hit Parade series. Finding somewhere to play original music wasn’t easy, says Butler: “Most venues wanted bands that played covers. Wits University was one of the few places where you could play original music.”

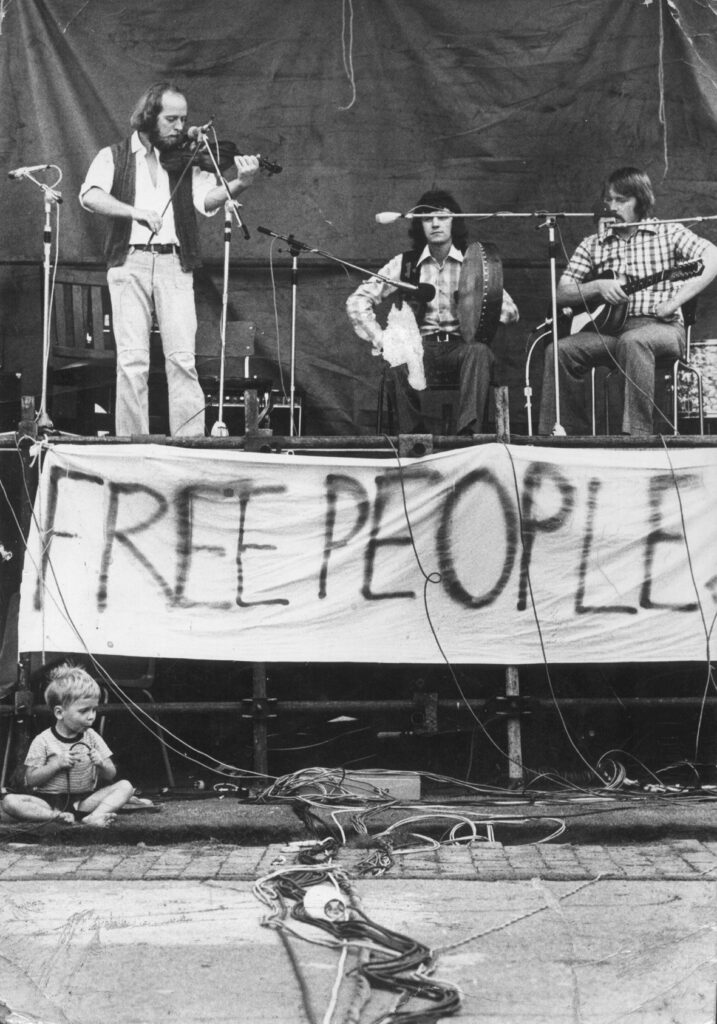

The Free Peoples Concerts

Sage performs at a Free Peoples Concert. People of all races could attend because if an event was free and the performers played for free, there could be no restrictions. (Frank Black/ The Star / The Hidden Years Music Archive Project)

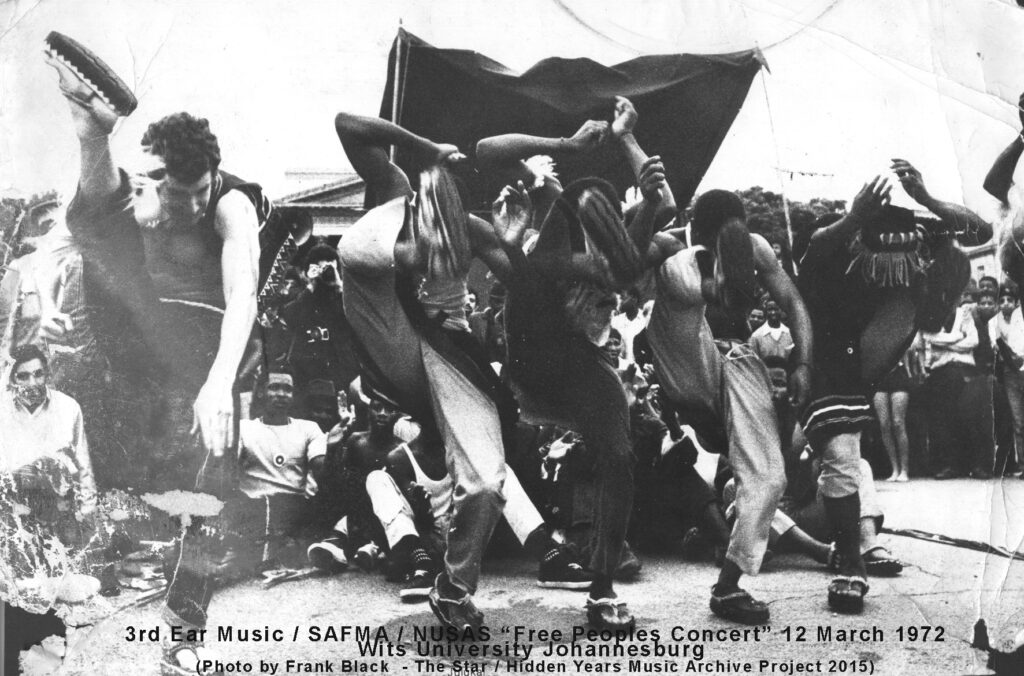

Sage performs at a Free Peoples Concert. People of all races could attend because if an event was free and the performers played for free, there could be no restrictions. (Frank Black/ The Star / The Hidden Years Music Archive Project) Butler got to play on another Marks platform with a band called Benny B’Funk and the sons of Gaddafi Barmitzvah. These were the Free Peoples Concerts, which started at Wits in 1971 (after one gig in Durban) and then at various larger venues until 1986. Marks had worked with Bill Hanley doing sound at Woodstock in 1969 and brought back part of the PA, which came to be known as the “Woodstock bins”, and these warmed the ears of grateful festival audiences across Southern Africa for decades. He was able to hold the Free Peoples Concerts by exploiting a loophole in an apartheid law: if the event was free and the performers played for free, there could be no restriction on who attended.

These concerts provided a sense of what a different or “normal” society could be; and, because they brought black and white people together, they gave the authorities “the jitters”. Mail & Guardian’s Shaun de Waal wrote that songs like James Phillips’ Shot Down, Brain Damage and Darkies Going To Get You “evoked the terrible emergency years and spoke directly to the hearts and minds of a youth taking a cold hard look at who they are as white South Africans”.

Osrin says: “The apartheid censors didn’t seem to grasp the power of music to bring people together – they could have policed it a lot more.”

Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu, who formed Juluka, also performed at a Wits Free Peoples Concert. Clegg, who was studying at Wits University, was first recorded by 3rd Ear Music. During Tribal Blues — another show that Marks arranged — Clegg, Mchunu and 32 waMadhlebe dancers “stomped their way through the Wits Great Hall’s brand-new ‘sprung’ wooden stage. I was held personally liable,” recalls Marks, who also introduced Ladysmith Black Mambazo to Johannesburg’s white audiences.

Johnny Clegg, Sipho Mchunu and waMabhlebe dancers at a Wits Free People’s Concert. (Frank Black/ The Star/ The Hidden Years Music Archive Project)

Johnny Clegg, Sipho Mchunu and waMabhlebe dancers at a Wits Free People’s Concert. (Frank Black/ The Star/ The Hidden Years Music Archive Project)

Restrictions on black musicians

The movement of black musicians or bands of mixed races was restricted by them having to get permits. To get around those barriers, they had to be resourceful. For example, mixed-race bands sometimes did lunchtime gigs in Johannesburg so their black members could get home before the nighttime curfew. Marks says: “It was relatively easy for us ‘whites only’ middle-class protesters to organise and then to shout the odds from the distant ‘platforms’ we provided, in the suburbs and cities. It could’ve meant intimidation (or worse) for those musicians sneaking back into the townships after one of our ‘protest’ festivals or ‘communist’ inspired concerts.”

Black artists who were being harassed sometimes chose to “do a Pinocchio” — skip to another country illegally. Jazzophile and blues crooner Cameron “Pinocchio” Mokaleng started this trend in the late 1950s after Sophiatown was razed in 1955, according to music journalist Sam Mathe. Mokaleng was followed by several members of the cast of King Kong in 1960, including Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela. They and Abdullah Ibrahim, who also chose exile, became better known on foreign soil than in their home country.

Black protest musicians who chose to stay could face stiff penalties. Vuyisile Mini, who wrote Ndodemnyama (Beware, Verwoerd), was arrested in 1963 and was hanged, ostensibly for killing a police informer. Activist Ben Turok wrote that he heard from his cell how Mini sang freedom songs on his way to the gallows.

White musicians got off more lightly. Roger Lucey was pursued in what became a personal vendetta for Paul Erasmus of the Bureau of State Security; he ensured that Lucey couldn’t get concert gigs and that his songs were banned. The saga, which ends in an unexpected twist, is brilliantly outlined in the Lucey rockumentary Stopping the Music.

Erasmus describes in Stopping the Music how he threw a teargas grenade into the air conditioner at a club called Mangles, another venue run by Marks, during a Lucey gig. Erasmus also reveals that he and his cop buddies used to “toss the odd petrol bomb” into Crown Mines, Johannesburg, where Lucey and other politicos lived. Black protest artist Mzwakhe Mbuli, who was constantly harassed for speaking out, had a dud grenade thrown into his baby’s bedroom in the 1980s.

This constant pressure from the authorities led Marks to give a Lucey recording the bizarre title of Weight Lifting for Catholics from a Mad magazine cut-out, and to label Lefifi Tladi’s recordings Abba’s Greatest Hits.

The Special Branch was also adept at sowing distrust, of pitting people against each other, and infiltrating organisations and movements with spies. Marks says: “We mustn’t forget … Major Craig Williamson … who nobody, despite what they say today, suspected of being a spy. He was one of those who helped me organise a few Wits events … a ‘cheerleader’ with megaphone, who led those famous Jan Smuts Street protests … ‘free all detainees’ — with the new Rand Afrikaans University students pelting us with eggs, fruit and rocks, from behind the police lines.”

Shifty and cassettes

In the audience of a Free People’s Concert was a musician called Lloyd Ross, who had had a hit with the soundtrack for the Afrikaans prison series Vyfster. Between doing sound on movies he set up the indie label Shifty Records, and decided its first project would be to record the Lesotho band Sankomota, which he did by parking his mobile studio outside the defunct Radio Lesotho and running a cable into one of it’s rooms.

But no major South African record company was willing to release the album. “Firstly, they sang in different languages, which violated grand apartheid’s pipedream of keeping all languages pure and separate. Secondly, the lyrics referred to what was really happening in the country, which was of course a total no-no. And finally, the music was eclectic, a concept that has confused industry marketing departments since the invention of the gramophone,” recalls Ross. But over time, however, the Sankomota album sold more than 25 000 copies.

Another big seller recorded by Shifty is Mbuli’s Change is Pain album, but because “the people’s poet” was an outspoken protest artist, innovative ways had to be found to distribute Change is Pain. Mbuli’s first album came out on the cheap medium of cassette; these were placed unmarked in paper bags for distribution.

Mark Bennett, who did sales for Shifty from 1983 to 1990, says he used an informal network to move the album. “I kind of developed this hawker network. And then there was a guy in town on Market Street called Whiskey who had a general dealer kind of store, like a bicycle shop, who had a team of hawkers, and he used to move a lot of stock for me.” Shifty stock was also sold at flea markets such as the one in Greenmarket Square in Cape Town, and distributed by trade unions after Ross recorded the Federation of South African Trade Unions choir.

Osrin, who produced “somewhere between 600 and 800 black acts”, says that Teal used to release about 80% of their music on cassette, which were cheaper and more mobile than LPs, which suited black buyers. “We only brought LPs out if we wanted the presence of an artist in the shops,” he says.

Warrick Sony, who also did a stint at Shifty, says the Kalahari Surfers’ first release was the cassette called Gross National Product, which came out in Italy, where there was a big cassette movement. Shifty, which self-financed their productions, brought out most of their products on vinyl and cassette, which were a robust and inexpensive way of mass producing music, and a way around the system.

“Every now and then Shifty would get raided,” says Bennett. “They took all of our A Naartjie in our Sosatie and Sankomota albums, but we had these lawyers who chatted to the cops and said this is ridiculous, because they weren’t formally banned. I then had to go to John Vorster Square [police station], which was a very weird experience, because I had to go up to the 10th floor, and I got sent into this room where there were these three really dodgy-looking Dutchmen, and there was a shopping trolley in the middle of the room with our stock in it, surrounded by piles and piles of porn. I was worried that I wouldn’t get out of there again, but I just pointed and said, ‘I’m here to fetch that stock’ and they said ‘sure’ and I just walked out with the trolley.”

Radio airplay

Getting radio play in South Africa was difficult because the state-owned SABC dominated the airwaves and enforced the Films and Publications Act.

Radio Freedom, the ANC’s propaganda arm, broadcast from Tanzania, Zambia, Angola and Madagascar in the 1970s and, aside from providing news of the Struggle, it also played exiled local musicians such as Dudu Pukwana. South Africans who tuned into it could, if caught, earn themselves a prison sentence of up to eight years. LM Radio helped to promote many South African bands who couldn’t get airplay from the SABC, but it closed in 1975.

“Protest songs were often played by Radio Bop because it had more reach than other radio stations based in countries like Swaziland, and could be accessed by residents as far afield as Soweto,” says Osrin. “The loophole that Radio Bop exploited was that Bophuthatswana was an ‘independent homeland’ — supposedly another ‘country’ — so it could play songs that the SABC couldn’t. Once it had played a song that became popular, however, demand was created, and the SABC sometimes followed suit and started playing it too. Many musicians, including Juluka, also played gigs in ‘homelands’ where the police were less likely to arrest musicians.”

After apartheid

Asked if South Africa’s record industry is giving artists what they need, such as support for up-and-coming talent, Marks replies that those who control the “record” industry still only have one aim — to make a profit.

“One has to only look — listen if you dare … there’s almost nothing that is ‘musical’ or audio — about the state of our annual South African Music Awards circus. It may be a great media spectacle with lots of ‘talent’ and fun and good times, but it has nothing to do with music. It is a record industry event … Indigenous music — traditional, classical, contemporary — is blown away by the countless so-called ‘music’ events that the ‘record industry’, the media and the state-owned entities spend billions of taxpayers’ money producing. This has nothing to do with music or musicians.

“If only history could help us understand the vacuum, the divide between creating, making and sharing music and the production and the selling of clinically recorded video bling, bang and bombas,” Marks says. “It’s a dogfight out there in the record industry that musicians should not be distracted or fooled by. They should do what indies or archives such as Shifty Records, Mega Music and the International Library of African Music did, and that is to ignore those material competitive events, and just do what you can do as a musician.

“Minstrels and troubadours in Africa have been playing village to village for centuries, and surviving into old age. Then along comes the Idols industry and record label vultures, and there’s only one function or criteria, and that is to attract the numbers, which, to a creative soul, destroys the dream. They are told, as creative people, to be practical and die doing so. Musicians today are far more ‘valuable’ dead than alive, so it’s only in decomposing that we really ‘make a living’.”

Recognising Marks’ work

And we thank you, Master Jack: David Marks performing at Africa Bike Week in Margate in 2018. (Ken Etburg)

And we thank you, Master Jack: David Marks performing at Africa Bike Week in Margate in 2018. (Ken Etburg)

Marks has been described as “difficult” and as a man “with an axe to grind” and he says he’s been omitted from many accounts. He may have a point: there’s not even a Wikipedia post about 3rd Ear Music, and Wikipedia’s post about him is all of two tiny paragraphs long. This, for a man who set up Splashy Fen, organised the Free People’s Concerts, ran several alternative venues and recorded and brought several musicians into the limelight.

Has the state recognised his work? “I’ve sat in committees, at approximately 32 arts and culture department’s tea-and-biscuit-break costly 5-star hotel KFC indabas, think tanks, workshops and imbizos, where the role of 3rd Ear Music, myself and the Hidden Years collection has been discussed and lauded … and impressive resolutions were passed … and then nothing happened,” he says.

Now aged 76, he still waxes lyrical on the 3rd Ear Music website, but he’s given up on writing a memoir and is entrusting that Lambrechts will use his archive to tell his story. “It’s all down there, recorded somewhere. The music material is in Stellenbosch, and the researchers must make of it what they can.”

Lambrechts says she and her staff have made good progress with the digitising process, and they’re developing an online platform to host the decades of music material Marks has entrusted them with.

“I was once in a position to organise events, press play and record,” says Marks. “Now I press pause, rewind and play.”

First published on the Music in Africa website