Jakkie Cilliers’s book about igniting a growth revolution in Africa has some timely lessons as we seek ways to mitigate the economic effects of Covid-19.

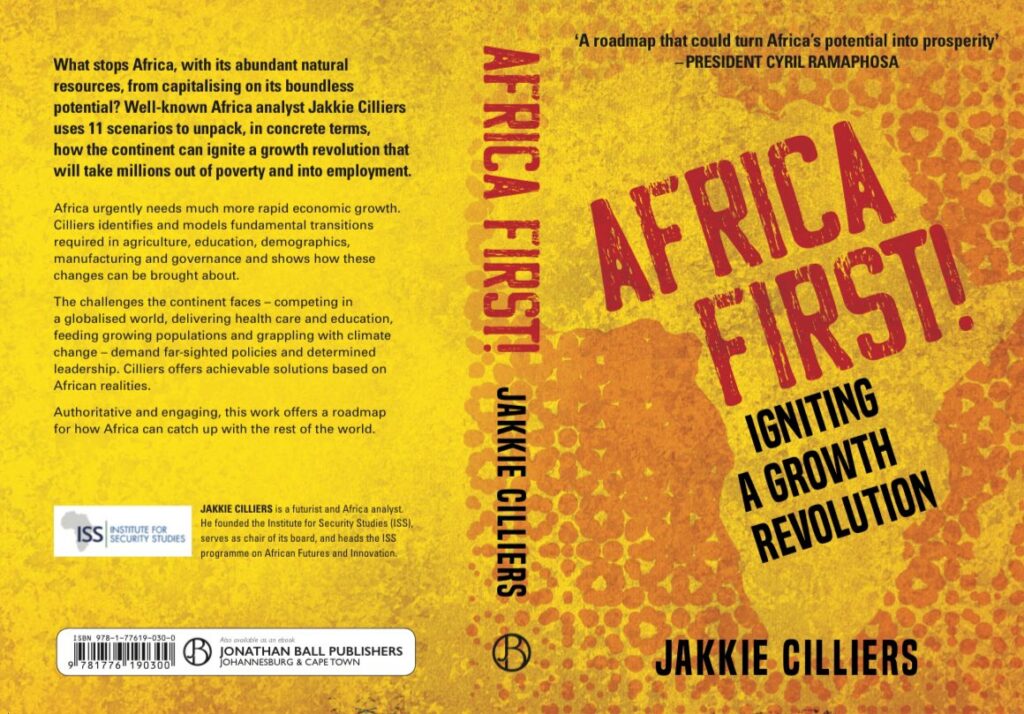

Africa First! Igniting a Growth Revolution by Jakkie Cilliers (Jonathan Ball)

Africans are holding their breath; waiting to see what the real effects the Covid-19 pandemic will be in the coming weeks and months. Clearly, no one knows whether the drastic measures taken in many African countries, such as closing borders and ordering lockdowns, will be enough to prevent a catastrophe.

What we do know is that many things probably won’t be the same post-Covid-19.

And, if we’re lucky, this might just be the moment African governments begin doing the right thing. Instead of focusing on staying in power or waging war, they might just start prioritising the wellbeing of their citizens. If that happens, some of the good practices put in place during the coronavirus crisis could turn things around for those desperate for greater solidarity, better health systems and less inequality.

If this is the case, the new book by Jakkie Cilliers, the head of African futures and innovation at the Institute for Security Studies, could come in handy.

On the cover of Africa First! Igniting a growth revolution, President Cyril Ramaphosa himself promises that this is “a roadmap that could turn Africa’s potential into prosperity”. That prosperity is of course extremely difficult to achieve, even with governments that are willing and able, given Africa’s backlog in relation to the rest of the world.

Clearly, some of the projections in the book regarding growth rates — particularly over the short term — will soon be outdated because of the devastating effect of the virus on economies worldwide. But the central message of the book, that African governments need to start doing things differently to improve the lives of the poor and to ensure economic development that benefits everyone, is now more valid than ever.

In a wide-ranging discussion of all the various challenges Africa faces, Cilliers charts 11 different interventions that African governments can make to ensure a better quality of life for their citizens. These include quality education, agriculture that feeds the nation, manufacturing that adds value to raw materials, infrastructure that vastly increases productivity, and the ambitious African Continental Free Trade Area.

The suggested interventions are all backed up by solid research and data from the International Futures data platform based at the Frederick S Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver. These show the interactions between the various proposed interventions and how they will play out over the next few decades. For example, if education indicators improve, others such as growth and stability also improve and vice-versa.

Examples of how China and other countries succeeded in achieving high growth rates and reducing poverty are instructive. When negotiating with foreign investors, for example, China has ensured the transfer of knowledge and technology, upskilling its own workforce, while African governments more often than not snip the ribbon of the new bridge or railroad without any regard for which new technology will have a lasting effect.

Demographic dividend?

Some of the issues in the book are well known and already the object of much debate. This is true, for example, concerning the tricky subject of the demographic dividend. It has been said many times before — by Cilliers and others who are bold enough to raise this uncomfortable truth — that although the percentage of people in Africa living in dire poverty is slowly declining, the absolute numbers of people living in poverty continue to increase due to the high fertility rates in many countries.

Although African leaders — including Ramaphosa — continue to speak of the youth as Africa’s greatest wealth and “endowment”, Cilliers shows that the figures are not in Africa’s favour as was the case, for instance, with the Asian Tigers, Japan and China a few decades ago, when the labour force was the biggest asset for rapid growth.

The so-called demographic dividend — when there are enough working-age people to support the younger and older dependents — will be reached in most African countries only far into the future if the current population-growth rates continue.

Ironically, then, as the book points out, it is precisely the low population density over the first thousands of years of existence of the human race that caused development in Africa to progress at a slower pace than elsewhere. Because of this low density, Cilliers says, people didn’t require competition-driven, cultivation and systematic farming, which lie at the foundation of human development.

On the subject of health services in Africa, the one that concerns us so much today, Cilliers predicts that although communicable diseases such as malaria, HIV/Aids, Ebola and others are still widespread in Africa, with the continent carrying a disproportionate share of these diseases, noncommunicable illnesses such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease will cost more to detect and cure in the coming decades.

Cilliers was clearly predicting the end of epidemics in Africa a bit too soon, but who could have predicted only a few months ago that Covid-19 would hit the world and cause such devastation?

At this point, we don’t know whether African elites, who are so used to travelling abroad for healthcare, will see the current crisis as a wake-up call to invest seriously in local hospitals and health facilities. Covid-19, that great equaliser, has shown the limits of a world of individuals selfishly hoarding wealth and not caring about our common humanity.

Some of Cilliers’s projections seem common sense, if only governments had the money and energy to focus on improving all these services; other recommendations in the book, however, are fairly unorthodox, certainly among those who religiously believe that by itself, the free market and direct foreign investment will be the wave that lifts all boats.

A developmental state

Cilliers clearly supports a strong role for African governments that “get behind success”. These governments should make the right interventions that will support the private sector, which, he stresses, is still the best guarantee for growth and job creation.

Cilliers flights the idea of social grants for Africa — a scheme that could draw millions of people out of poverty through cash transfers to the poorest of the poor. This is an idea that could certainly take off in a big way, given the Covid-19 crisis. The South African government is indeed now contemplating the doubling of child grants to help those people in the informal sector to cope with the Covid-19 lockdown.

Now that philanthropists in South Africa and Nigeria — and, hopefully, other countries — are promising huge amounts of funding to help in the crisis, there is a possibility for such cash payments to be increased and institutionalised. If African Union leaders are successful in obtaining debt relief from the G20, as they’ve recently lobbied for, this windfall could also contribute to such schemes to help the poorest of the poor.

Cilliers makes the good point that financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank have in the past adopted policies for Africa that were disastrous for the continent. The structural adjustment programmes of the 1980s saw a huge reduction in state capacity to provide basic services. The results of these policies are still felt today, particularly in the health and education sectors in many countries.

“The problem is that poor countries need an activist, developmental state if they are to engineer an escape from poverty,” says Cilliers.

Of course, and he makes the point several times throughout the book, this would need far-sighted leadership and “developmentally orientated governing elites”. In a recent article in the Financial Times, Yuval Noah Harari, famous for his book Sapiens — A Brief History of Humankind and follow-up books about human existence, said the coronavirus and the way government and societies respond “will probably shape the world for years to come”.

“Yes, the storm will pass, humankind will survive, most of us will still be alive — but we will inhabit a different world,” he writes about the crisis that could “fast-forward historical processes”.

“Decisions that in normal times could take years of deliberation are passed in a matter of hours,” Harari observes.

Better healthcare for all in Africa might be just one such decision.

No one knows at this point what the future holds, but if Covid-19 emerges to be the great disruptor, Africa First! could be a useful handbook offering a range of potential disruptors that will make Africa a better place.

Liesl Louw-Vaudran is a senior research consultant at the Institute for Security Studies.