Mongezi Feza on trumpet at the concert in 1964 that is the source of the rare new photos of The Blue Notes. (Norman Owen-Smith)

There is no doubt that when we speak about South African jazz, we speak about a gold mine. Rich in sounds, it boasts some of the finest musicians who have walked the streets of Johannesburg, Pretoria, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Durban, among other urban centres.

Its history is largely undocumented or remains fragmented because of the lasting effects of the oppressive apartheid policies on black performing arts. Look no further than jazz historian Christopher Ballantine’s sobering statement in his seminal book Marabi Nights: Jazz, ‘Race’ and Society in Early Apartheid. Here, speaking about the void of the jazz archive, especially that of the first six decades of the 20th century, he says: “… but the roots of the problem go deeper. Any attempt to recover the music of those earlier years — certainly this is true of the period before 1950, but in many instances, it applies to the period after it as well — is complicated by the shockingly irresponsible attitude towards its preservation displayed by institutions that arguably ought to have known better: in particular the record companies and the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC)”.

This condition may remain somewhat unchanged, but this is not to discount the crucial, groundbreaking work done by some individuals and institutions. For example, online, there is the ElectricJive archive, the jazz collections found at the University of KwaZulu-Natal music library and the Hidden Years Music Archive Project in which efforts to digitise and preserve some of this music, alongside other material, is the primary objective.

Arguably, more documentation and exploration still needs to be done as the untold stories and histories abound. As I write this, I am reminded of one project titled Before the Wind Changes.

The Blue Notes pictured collectively on the eve of leaving South Africa. (Norman Owen-Smith)

The Blue Notes pictured collectively on the eve of leaving South Africa. (Norman Owen-Smith)

Last year I was part of this special project at the invitation of jazz scholar Lindelwa Dalamba to intervene on a series of “forgotten” photographs of the Blue Notes, taken by scientist Norman Owen-Smith. An exhibition and lecture were presented at the University of the Witwatersrand. The young, aspiring lensman had captured the Blue Notes’ concert at the University of Natal Pietermaritzburg’s Great Hall in 1964, on the eve of their departure out of the country into exile. These rare images surfaced years later thanks to Owen-Smith’s instinctive inclination to preserve and later to bestow them for the purposes of research and creative engagement.

Dalamba writes that the photographs capture “a moment in the band’s history — in their teens and 20s — and just before they went into exile. They are a notable addition to a very thin archive”. This may have something to do with the band members Chris McGregor, Dudu Pukwana, Nikele Mokaye and Johnny Dyani dying, mostly in exile, and their music going for long periods of time without being released. The fifth member, Louis Moholo-Moholo is the only surviving band member.

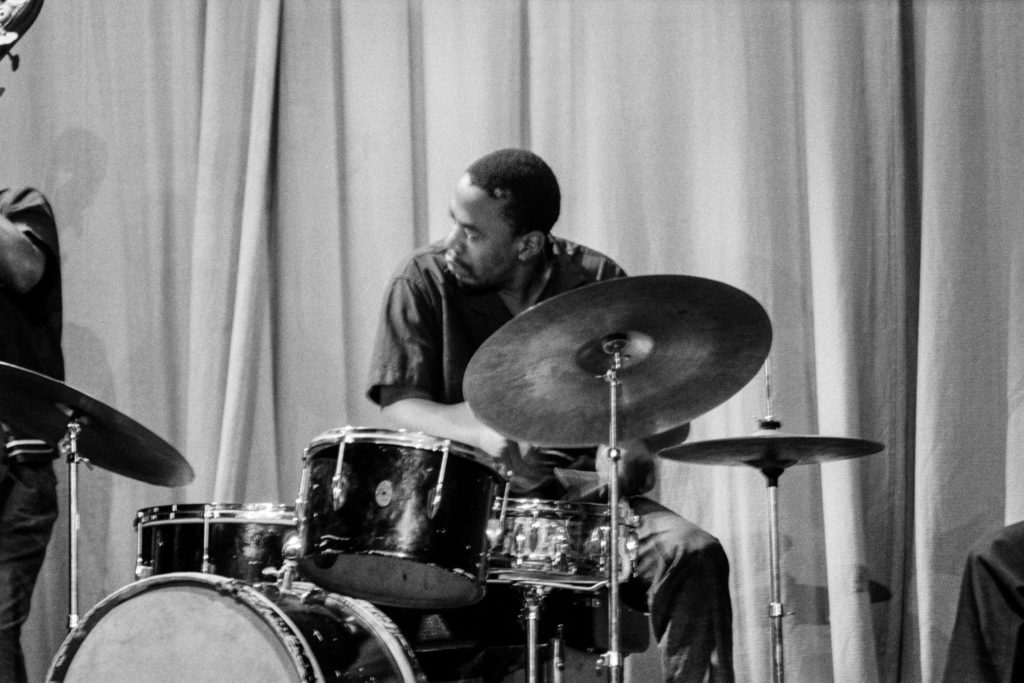

Legendary drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo is the sole surviving member of the band. (Norman Owen-Smith)

Legendary drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo is the sole surviving member of the band. (Norman Owen-Smith)

Tapping into the heritage

With today marking International Jazz Day, the City of Cape Town would have been abuzz with week-long activities of jazz through the event’s educational programmes, panel discussions, workshops and of course the livestreamed All-Star Concert which would have featured top-ranking jazz musicians from the United States and the home soil. Because of the global catastrophe that is the Covid-19 pandemic, International Jazz Day, like many other big events, has had to postpone its proceedings until further notice. Unquestionably this has caused instability and uncertainty and questions about what long-term effects for live music are at large.

In South Africa, these concerns are compounded by a dearth of jazz venues. Most that are still operational struggle to keep their doors open, many have shut theirs permanently. On this auspicious day, however, the show must go on and the celebrations have moved to the digital sphere where “at home” uploaded performances of musicians across the world can be streamed.

The organisers, Spin Foundation, have titled the 2020 jazz day “Tracing the Roots and Routes of African Jazz”, which it says, “is a way of honouring jazz heritage and making a significant contribution to writing Africa’s cultural history for generations to come”. The foundation’s chairperson Motsumi Makhene has stated that “the narrative of the ancestral origins will be told through learning about and owning our heritage, innovatively telling and preserving the story of Africa’s powerful influence”. These are noble intentions and should be pursued relentlessly.

But what about when the events have passed? Both today’s events and the eventual proceedings post the lockdown phase? What lessons will have been learned? What new meanings, if any, will the theme “tracing the roots and routes of African jazz” have for the hosting nation? As we connect with the world at large, following the links of South African jazz (through the complex story of the Blue Notes and their contribution to the London jazz scene, for example) as well as exploring other transatlantic and diasporic connections, may we remember that the South African jazz archive repository needs to be filled continuously and the creative research work remains paramount.

Boitumelo Tlhoaele is a Doctoral fellow at the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation (Stellenbosch University) working on the Hidden Years Music Archive project. Her research interests include the intersections of jazz and art.