Sometimes confused with their cousins, the starfish, they differ in having long whip-like arms. Most are scavengers, eating dead creatures and seaweed, although some filter food from the water. Photo supplied

About 410 million years ago, a group of brittle stars were sheltering in a drift of sea shells in a shallow sea when a pulse of mud washed out of a nearby river mouth after heavy rains. The sudden surge of muddy water engulfed the spiny sea creatures, smothering them alive.

Now, a team of researchers has pieced together the puzzle of the delicate fossils’ epic journey, publishing their findings in the scientific journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday. They are the oldest known brittle stars from the supercontinent of Gondwana, and were found in rocks in the Eastern Cape.

Their existence dates back to the Early Devonian, which occurred 420 million to 393 million years ago. Remarkably, they were found in near-perfect condition. They have been named Krommaster spinosus, after the Kromme River and their long, sharp spines.

The research was conducted at The Devonian Ecosystems Project, in collaboration with GENUS: DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences, of whom Rhodes University and the Albany Museum in Grahamstown are partners.

Frozen in time

Brittle stars, scientifically known as ophiuroids, are represented by about 2 000 species and have a long fossil record, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere, mainly living in the shallows of the sea.

Sometimes confused with their cousins, the starfish, they differ in having long whip-like arms. Most are scavengers, eating dead creatures and seaweed, although some filter food from the water.

Unlike other sea creatures, brittle stars disintegrate soon after death and finding them intact is rare. That’s why Caitlin Reddy, the master’s student leading the investigation, was stunned when the largest specimen was uncovered.

“The level of detail left us speechless — from the thin plates on its body to the tiny, bristly spines. This degree of preservation is astounding and very rare,” she said.

Reddy, who was completing her honours thesis in geology at the time, described how she painstakingly exhumed the largest specimen in May last year.

“A big part of my honours was actually breaking up those chunks of rocks and looking for new specimens. It was very late one evening and I was with one of my friends at the lab. We were just going through the rocks and I had a feeling that in this really thick part of rock, that something must be in there.”

Her friend was helping her break the rock in a certain way. “I wanted to break it along the thickest part and then flip the rock over. On our first try, we broke it open and we found that huge specimen and it was spectacular because it had all those disk scales still preserved.”

They are called brittle stars because they break apart easily. “The fact that they’re just intact like this really supports our idea that they were buried alive and they were buried quite quickly,” Reddy said. “It’s so amazing to open a rock and just be looking back at a frozen moment in time.”

How the discovery unfolded

The researchers said the little drift of shells was buried over millions of years under layers of mud and sand, which were ultimately transformed into rock and folded into mountains hundreds of millions of years later.

These weathered away until the cluster of fossil shells containing the brittle stars was disturbed by a small farm road in the Kromme River Valley near Humansdorp. The samples that Reddy analysed were first collected by Rob Gess in 2015, while doing the palaeontological section of an environmental impact assessment for a new power-cable route. Gess is South Africa’s leading researcher on Devonian ecosystems and early vertebrates.

No fossils were expected in the area, but he decided it would be best to walk out the whole proposed route because finding new fossil sites is often far more important than revisiting well-studied ones.

He was making his way down a small, recently graded farm track when he spotted an unusual orange lens of rock part graded out of the bank of the road. Looking closer, he realised that it was almost entirely composed of fossil lamp shells with brittle stars intertwined within them.

Realising this was something new, and not wanting to damage the delicate fossils, he removed some large chunks to archive in the Albany Museum collection for later research. There they waited, while other discoveries kept him busy, until Reddy came to his lab to unravel their intriguing story as a graduate student under his supervision.

“Rob was saying to me before I came and did the project that these rocks are stored in his lab just waiting for someone to work on them,” Reddy said. “We have this diary of all the events that happened on Earth and it’s just waiting for us as scientists to uncover it and make sense of it and share it with everyone else. It’s so important in terms of filling in the puzzle pieces of where we all come from and how we’re all linked and all of that wonderful stuff that palaeontology helps us understand.”

Master’s student, Caitlin Reddy. Photo supplied

Master’s student, Caitlin Reddy. Photo supplied

Detective work

Gess arranged additional supervision from Mhairi Reid, who did her master’s on younger brittle stars from South Africa, and later from Ben Thuy, who is the world’s brittle star expert.

The blocks archived in 2015 were carefully broken apart under laboratory conditions to reveal the three-dimensional preserved impressions of the ancient brittle stars. These are moulds in the mud rock where the original brittle star skeletons dissolved away hundreds of millions of years ago.

Brittle stars are made up of interlocking plates that are different in every species. To recover the exact shape of the plates, Reddy cast the imprints with black silicone, which showed that the new species had been covered in thorn-like spines. After the casts were whitened, they were photographed under a microscope for comparison with other known species.

This showed that the plates had a unique shape requiring a formal description of a new species. Reddy discussed her photos with her colleagues to produce an international standard scientific description.

“Thanks to the outstanding preparation and digitisation work by Caitlin, I was able to contribute to this exciting scientific study entirely by virtual means, working on high-resolution photographs of the fossils,” Thuy said. “None of the valuable and fragile specimens had to be shipped.”

Unearthing a new species

According to the team, the brittle stars prove to be a species new to science that so far is only known from this one small lens of rock. “Excitingly, they provide the earliest known record of brittle stars from the entire ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, which later broke up into Africa, South America, Antarctica, India, Australia and Madagascar.”

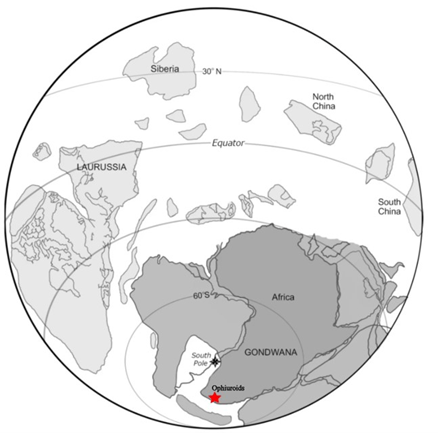

They belong to a group of brittle stars that were later replaced by the types seen today. They are also some of very few known from ancient polar regions, as Southern Africa was then within the Antarctic circle.

The majority of early known species are recovered from rocks formed nearer the equator, largely from the northern supercontinent of Laurasia, which later split into Europe, Greenland, North America and parts of Asia.

“I always find it incredible, almost magical, that we can find frozen in time, records of such passing moments,” Gess said. “Here, we are able to see these brittle stars, twined in among a drift of old seashells, exactly as they were one minute of one day, 410 million years ago, when they were suddenly smothered in mud.”

He said South Africa has an incredible fossil record “covering much of the history of life on our planet”.

“Indeed, it is impossible to write about virtually any aspect of the origins of life without referring to the South African fossil record — whether it is the earliest traces of life, the earliest plants, the origin of four-footed creatures, mammals, or dinosaurs or even people.

“And this is our collective story, the greatest story on Earth.”