South Africa’s economic crisis has been simmering for a while. Covid-19 brought it to the boil. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) to contract by 8% in 2020 as a result of the pandemic, which has plunged tax revenue and caused a large number of job losses.

Although all emerging markets are expected to experience negative growth in this fiscal year, South Africa’s expected contraction will be among the steepest, according to the revised IMF global economic outlook.

The outlook, which has been revised from April and was released earlier this week, shows that emerging markets will be worse off than previously thought.

Brazil (488 692 cases and 53 874 deaths as of June 25) and Mexico (173 642 and 24 324) are projected to contract by 9.1% and 10.5%, respectively, in 2020. The economy of India (271934 and 14 914) is expected to contract by 4.5% because of a longer lockdown and slower recovery than anticipated in April.

Oil producing countries such as Nigeria, Russia and Saudi Arabia have their economies crippled by the disruptions of the pandemic as well as the decline in oil prices. They are projected to contract by -5.4%, –6.6% and –6.8% respectively.

The average fiscal response to the pandemic among emerging markets is estimated at 5% of GDP, but these fiscal responses are against a backdrop of widening debt deficits, which are likely to increase by an average of 10% of GDP, according to the IMF.

South Africa is no different. The country began its fight against the pandemic from an economically weak position, having entered into a technical recession in the fourth quarter of 2019 and with an unemployment rate of just above 30% in the first quarter of this year.

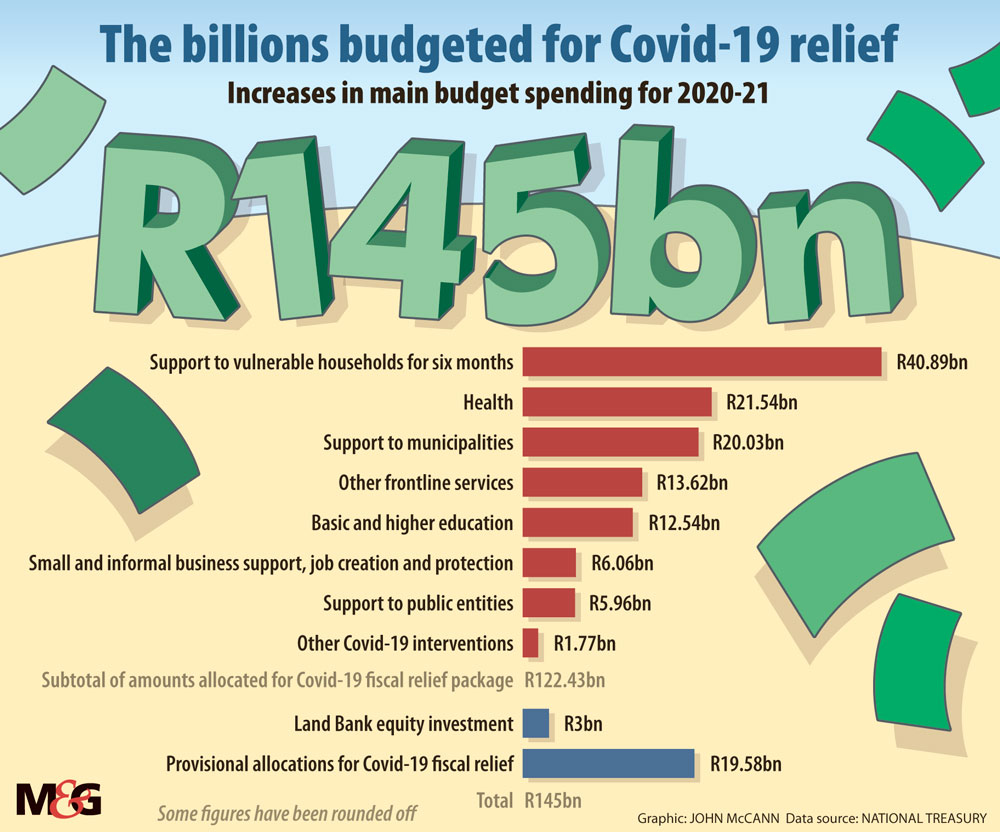

The country’s fiscal response to the pandemic amounts to 10% of GDP.

The country’s deficit is set to widen. In a supplementary budget in response to the Covid-19 crisis, the treasury projected the main budget deficit would reach 14.6% of GDP in the 2020-2021 fiscal year, revised from 6.8% announced in the February budget.

As a result, public debt is expected to reach its highest level at 81.1% of GDP in 2020-2021 from 65.3% last year, the treasury said.

South Africa has sought external support because it is not financially equipped to combat the effects of the pandemic. The government intends to borrow US$7-billion from multilateral finance institutions for its Covid-19 response.

The New Development Bank has already approved a $1-billion loan, and the country awaits the IMF’s decision to provide the country with $4.2-billion through the its rapid financing instrument.

On Wednesday, when presenting the supplementary budget, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni described the negotiations with the Washington-based lender as “tough and difficult”. He said that once the IMF agrees to provide South Africa with the funding, the World Bank will follow suit. This decision is expected in July.

Mboweni emphasised that the funds from the international financiers is “not revenue” but money that needs to be paid back at some point “with the requisite interest”.

“In an ideal economic environment, this type of loans acquired internationally should be used for investments … but we are in a crisis,” Mboweni said.

He made sure to announce that South Africa is heading towards a debt crisis if its finances are not handled with care.

Nthabiseng Moleko, a development economist at the University of Stellenbosch Business School, said the treasury has put emphasis on the debt to GDP ratio and the increasing debt, but the ratio is increasing because growth is contracting. Mboweni said little in his supplementary budget on the growth plan and how the economy will be stimulated.

Moleko said South Africa’s economic growth problems were there prior to the pandemic, which were an indication that the economy is not growing.

She said countries that make up the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have taken a much more aggressive and decisive approach aimed at stimulating economic activity. But South

Africa has not done much to boost the economy and increase aggregate demand by at least using additional measures on top of the normal reset measures such as lowering the repo rate.

“Let us look at new ways to reinvigorate our economy. Let us not be scared of fresh ideas. Let us not be scared of alternative economic models and thoughts. And different ways of using our trade policy and monetary policy where we target full-employment and job creation as the game changer”, Moleko said, adding that the country keeps doing the same thing yet expects different outcomes. As a result, she said, the inequality gap is widening and growth is being constricted, thus increasing job losses.

PwC’s chief economist, Lullu Krugel, said domestic fiscal policy measures and the implementation of economic reforms in the next six to 12 months will determine South Africa’s growth trajectory over the next several years. Absent these measures, there will be prolonged weakness in economic growth, she warned.

But Krugel said there have been no new measures in the government’s supplementary budget to expand the economy, which raised “strong questions as to the ability of the state to reform the economy out of its recession, and in turn the ability to reduce the fiscal deficit and stabilise public debt”.

Although South Africa has money woes, Krugel said that the weak economic condition will result in additional pressure on the struggling state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In his budget, Mboweni allocated R3-billion to recapitalise the Land Bank, which had asked for a cash injection of R22-billion early this year.

Mboweni said the treasury “is supporting the Land Bank to find a solution to its default and craft a long term restructuring plan”. No other SOEs were allocated money.

The PwC said the need for broad-based reforms at SOEs, to make them more “efficient and financially sustainable”, is even more urgent than before.

It said this could be done by reducing the number of SOEs, incorporating certain of their functions into central government, seeking equity partnerships and ensuring stronger policy certainty and implementation.

It said that planned financial transfers from the fiscus to SOEs should be strictly conditional on improving their balance sheets.

Thando Maeko & Tshegofatso Mathe are Adamela Trust business reporters at the Mail & Guardian