(Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

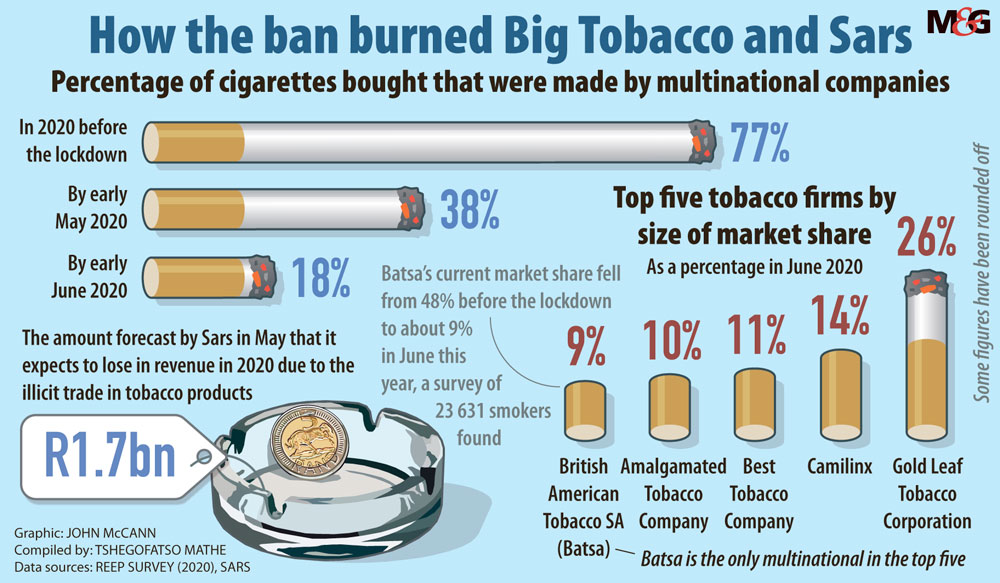

The nearly five-month ban on the sale of cigarettes has exacerbated South Africa’s illicit tobacco trade problem, and exposed the inability of the South African Revenue Services (Sars) to fight it, experts say.

According to Professor Corné van Walbeek, director of the Economics of the Excisable Products Research Unit (Reep) at the University of Cape Town, the ban has cost Sars R1.2-billion per month on excise tax, with a total of about R4.8-billion so far.

But Sars says that its integrated strategy, which it is still refining, is working and has produced some results including collecting revenue of about R191-million in the past five months. This, however, follows Sars’s cancellation of the track-and-trace tender because of concerns that Commissioner Edward Kieswetter said were raised when he arrived in May last year.

“I was concerned about how the track-and-trace system would support the new Sars strategy … on the illicit trade in tobacco. The track- and-trace system is but one mechanism at the end of the supply chain. The Sars compliance strategy on the illicit trade in tobacco is premised on data-driven prioritising and co-ordinating control of the entire supply chain, from the fields where tobacco leaves are grown, or the port of entry, to the final purchase by the individual consumer and enforcement of tobacco regulations,” he said.

Cigarettes under lockdown

In the interim, the lockdown has led to an under-recovery of R82-billion of taxes for the fiscal year through July 15, Kieswetter said in an interview with Bloomberg.

Although the illicit trade market has been thriving in South Africa for years, the ban has exposed Sars’s seeming inability to control the cigarette supply chain.

Professor Lekan Ayo-Yusuf from the Africa Centre for Tobacco Industry Monitoring and Policy Research, which offers up-to-date information on activities and developments in the tobacco industry, said that the ban has also amplified and exposed the already existing underhand activities of the industry.

“In fact, we believe that the decision of the government to allow the industry to resume production of cigarettes in May, supposedly for export only, fuelled the illicit trade as these cigarettes might have either not eventually been exported or were exported only to return to the country (round-tripping).”

Van Walbeek told the Mail&Guardian that their research shows that only 1 to 2% of popular cigarette brands were sold during the lockdown compared to 70% before the ban was enacted.

South Africa’s tobacco industry is run by multinational companies such as British American Tobacco (BAT) and Philip Morris International. Then there are independent or local producers which fall under the Fair Trade Independent Tobacco Association (Fita). Companies in this group include Gold Leaf Tobacco Corporation and Carnilinx Tobacco Company.

In a statement released by British American Tobacco South Africa (Batsa) this week, it called on the South African government to ratify the World Health Organisation (WHO) protocol to eliminate illicit trade in tobacco in order to eradicate the illegal sale of cigarettes in the country — which it claims is the largest in the world.

Batsa said the ratification would mean that the country would implement global WHO track-and-tracing guidelines. The tobacco company said that its market share has dropped from 48% prior to lockdown to 8.7% in June.

Batsa said the brand RG, which is owned by Gold Leaf, managed to sell 10-million cigarettes every day during lockdown at prices that were up to five times higher, despite no tax being paid.

Van Walbeek said: “All cigarette companies have been involved in selling cigarettes during the lockdown, some are just more successful than others.”

He explained that Fita had the advantage even before the lockdown in that they were entrenched in the informal market where they would sell their products to informal traders, street vendors, spaza shops —and not necessarily formal shops or big retailers. “They had a good pipeline into the informal market,” he said.

“All the formal shops, supermarkets, garages; they kept to the rules quite significantly because they knew that they were being watched.”

Track and trace

Last year April, Sars issued a track- and-tracing tender, but it was pushed back. The technology would allow for Sars to see upfront where the product is intended to go and the route it took from the manufacturer.

The tender has been extended four times since the first extension on August 30 2019. This was to allow the new commissioner to apply his mind and consult.

On May 10 2019, Sars had a non-compulsory briefing session for prospective bidders for the production management and track-and-trace solutions for cigarettes. The M&G saw the register, which recorded companies such as Tobacco Institute of Southern Africa (Tisa), Bidvest, BAT and Deloitte as bidders.

Kieswetter told the M&G this week that those who had applied for the tender and others raised concerns about the nature of the tender specifications and the level of consultation, among other issues.

He added that there were no adequate reasons for investing at the end of the tobacco value chain as opposed to the beginning or middle.

He also said that the proposed governance that would come with the system would contradict the WHO’s view that track-and-trace be under government control.

“Sars continues to refine its compliance strategy on illicit trade in tobacco in consultation with the rest of the government.”

A way forward

At this stage, it seems Sars is still building its strategy to adequately fight the illicit tobacco trade. Van Walbeek said he does not understand why the revenue service is stalling because the technology exists and is used for medical products.

Ayo-Yusuf said that the biggest obstacle is the tobacco industry and their allies. He said they should demonstrate political will. Only six years ago the revenue service was well on track to getting a handle on the illicit trade but the previous unit, designated to fight the illicit economy, was disbanded in 2014 during Tom Moyane’s reign.

In 2018, the revenue’s acting commissioner Mark Kingon reintroduced the illicit economy unit, which is meant to counter illegal markets, including cigarettes. Though no details are available about the work of the new unit, Sars has in the past five months seized cigarettes to the value of R92-million, has collected revenue of about R191-million and collected 639 outstanding returns.

According to Kieswetter, the revenue service will continue to refine its compliance strategy in consultation with government and law-enforcement agency partnerships.