Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. (Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Ailing state-owned airline SAA has been revealed as one of the reasons that under-pressure Finance Minister Tito Mboweni postponed the medium-term budget policy speech (MBTPS) due to have taken place on 21 October.

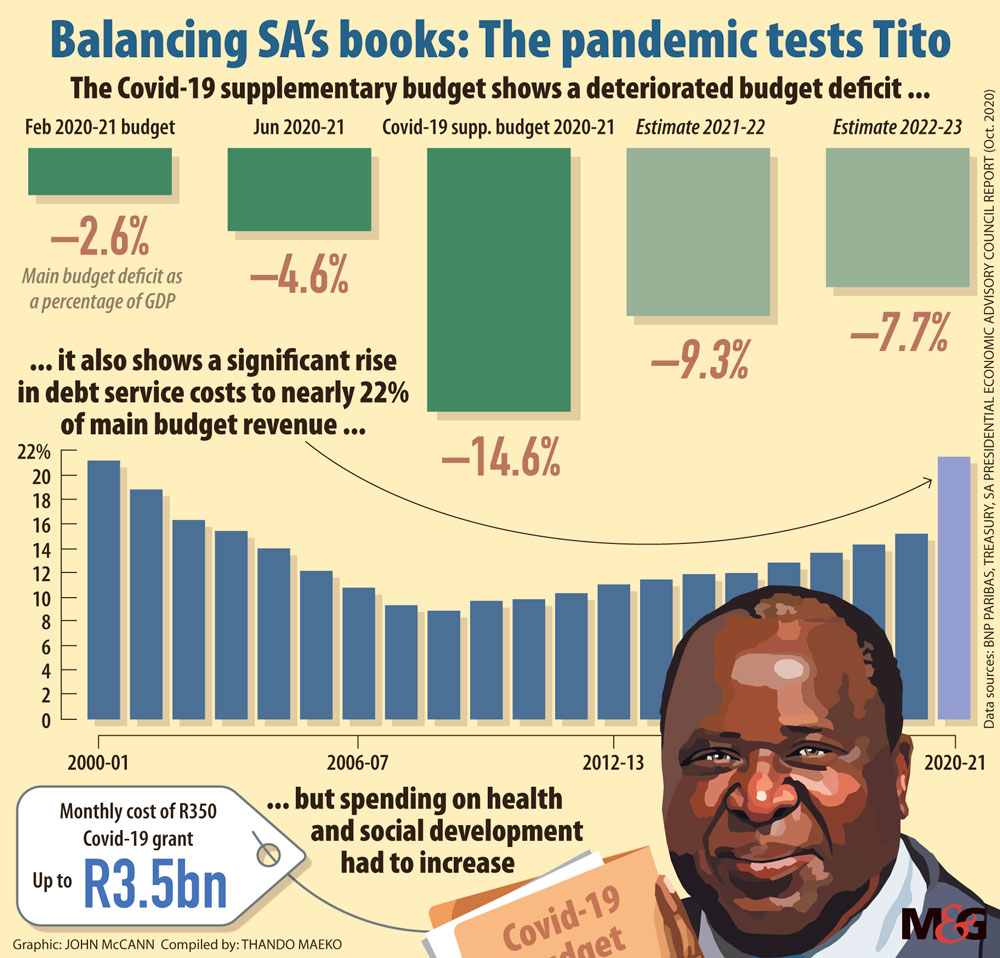

Mboweni also has to balance consolidating a crippled budget, ravaged by Covid-19, with added stress to announce the extension, by a further three months, of a temporary Covid relief grant that has gone out to six million South Africans, and funding for public sector salary increases.

Both of these will easily cost billions of rands the South African purse just does not have.

The Mail & Guardian spoke to various sources with intimate knowledge of the subject this week.

“There has been concerted pressure from labour (supported by business) and community activists that these cannot be discontinued while the economy continues to be in such a precarious state, and unemployment is on the rise,” one of them said.

“The government agrees, but more work needs to be done to find the money and make difficult decisions.”

Mboweni was expected to deliver perhaps his most difficult budget since taking over the reins at Church Street, Pretoria — South Africa’s fragile economy is ready to collapse after years of corruption and misguided expenditure — but news broke late on Wednesday that he had asked Parliament for permission to postpone his address by a week.

“The Money Bills Amendment Procedure and Related Matters Act, 2009, requires the Minister of Finance to table an MTBPS at least three months prior to the main budget. In this regard, the minister of finance has the prerogative to select any date that conforms with this requirement, including as it relates to the need to ensure that the appropriate consultations and technical processes are completed,” the national treasury told M&G.

They added that details of the final decisions will be communicated when the MTBPS is tabled.

Seeking to explain why treasury would need more time, a senior ANC member said: “There was a lot of work still to be done on modelling some of these things [ideas and plans in the various documents].”

The focus, they said, is on the special grants, the public sector wage bill with labour unions still determined to hold the government to year three of the wage agreement signed back in 2018, and the ongoing crisis at state-owned companies with SAA and Eskom topping the agenda.

SAA mess threat to budgets

The M&G has learned of a desperate race to secure R10-billion to fund the airline’s business rescue plan inside the treasury, so much so that it eclipsed critical consultations on other important announcements in the “mini-budget”.

Cabinet’s meeting on Wednesday failed to decide on the source of funding for the beleaguered state-owned airline. On the same day, however, public enterprises director-general, Kgathatso Tlhakudi told Parliament’s portfolio committee on public enterprises that an announcement on the financing of the airline’s rescue plan would be made during the MBTPS at the end of October.

Several other people with knowledge of internal discussions about the crafting of the budget said the desperation to secure funding led to several meetings with the four commercial banks that already carry significant SAA debt.

Mboweni and his public enterprise’s counterpart Pravin Gordhan made a last-ditch attempt to get funding at meetings with the banks, but these efforts were all rejected.

“When that failed they scheduled a teleconference with the president, them, and the banks, but this did not happen,” the insider said.

“At some stage, this proposal was called ‘bridging finance’, and the ministers promised that Tito would announce this allocation at this budget, but the money would only be made available in February. But this presented a problem for the banks.”

Public Works Minister Patricia de Lille then offered R1.5-billion in savings from renegotiating lease contracts, but this too was thwarted because she did not understand that the savings were for client departments and not hers, three sources with direct knowledge said.

When asked, De Lille said Cabinet discussions were confidential so she could not comment.

Senior officials at the treasury and public enterprises were left scrambling to secure alternative sources for the funds less than 24 hours before President Cyril Ramaphosa was meant to unveil his grand plan for pulling South Africa’s economy out of the doldrums after the disastrous effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Wages and debt

Another real concern is that South Africa’s ability to make its rising debt repayments has been severely impaired by the pandemic. Before the lockdown, the country’s debt to gross domestic product ratio had risen to 62.2% in 2019, and the cost to service debt was R230-billion.

Post-Covid, the impairment will be even more severe. In June, Mboweni revealed that gross tax revenue collected in the first two months of the current financial year was already R35.3-billion off the forecast.

With more than 2-million jobs lost it will be very difficult for Mboweni to balance the wage bill with a declining tax revenue base.

In papers filed before the labour court to oppose an application by labour unions to enforce implementation of year three of the 2018 wage deal, national treasury director general Dondo Mogajane says the implementation of the agreement would increase government’s debt by R37.8-billion “during a worldwide crisis”.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has come at great cost to employment in the private sector … The applicants’ members’ jobs are, in contrast, not threatened. Nor are their salaries reduced,” he said. Mogajane also challenged the legality of the agreement, saying that then public service minister Faith Muthambi ignored advice from the then finance minister Malusi Gigaba to approve lower increases, and effectively signed an agreement without written approval from treasury as required by law.

The failure of the government to implement the deal this year has angered public-sector unions.

Trade union federation Cosatu’s chief negotiator Mugwena Maluleke has not ruled out the possibility of further worker unrest should the wage deal not be implemented: “[When] you close the door for an engagement, the only door left open is for action and nothing else.”

Corruption and populism

“When you imagine expenditure being problematic you must appreciate that though corruption and populism are independent of each other, they both have a devastating impact on a country’s economy,” said another insider with decades of public sector budgeting experience.

He argues that though citizens are coming to grips with the cost of corruption, they need to be wary of expenditure that will not bring in revenue at a time when borrowing only serves to tighten the noose.

“In the previous administration the attitude from the top was that the treasury ‘must find the money’ … In the second term it became worse because finance ministers were being removed and that was to send a message to the next one,” said the insider.

The cost of corruption is currently being detailed in the judicial enquiry into allegations of state capture. In one instance, which has led to the arrest of Blackhead Consulting’s chief executive Edwin Sodi, the Free State provincial government paid R230-million to the company for work that could have been done for R21-million.