At the coalface: In a statement, President Cyril Ramaphosa described the political declaration as a “watershed moment not only for our own just transition, but for the world as a whole”.

Banks worldwide are buckling to pressure from shareholders to end fossil-fuel financing, with Europe’s HSBC becoming one of the world’s largest banks to announce a plan to end all new coal financing on 11 March.

This represents a significant move by Europe’s second-largest fossil-fuel financier and is another indication that the global banking system is slowly adjusting to the reality of climate change risks.

So how did HSBC, a bank that has committed $86.5-billion in fossil-fuel financing since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, suddenly change its investment path? The answer is shareholder engagement.

Shareholder-engagement groups are proving to be effective in facilitating conversations between experts, NGOs and large shareholders that result in important resolutions tabled at annual general meetings (AGMs).

In the case of HSBC, NGO Share Action successfully convinced a coalition of shareholders and institutional investors with a joint value of $2.4-trillion to file a resolution calling for the bank to release its plan to end coal-fired-power financing.

“HSBC provided billions in loans and underwriting to companies heavily exposed to coal and building new coal power plants since the signing of the Paris climate agreement,” said Wolfgang Kuhn, director of financial sector strategies at Share Action. “The amounts are not significant in the context of HSBC’s enormous balance sheet. Still, they are enormous in the context of a carbon budget, which is quickly heading to the red.”

After the resolution tabled in January this year, ahead of HSBC’s AGM in May, earlier this month the bank announced its plan to phase out coal financing, prompting the coalition to withdraw their resolution. In a letter written to the bank’s chief executive, Noel Quinn, and chairperson, Mark Tucker, the coalition welcomed HSBC’s decision.

“The focus now must be on putting these plans into practice. We look forward to working with the board on the development of its targets and plans. HSBC’s coal phase-out plan is particularly urgent, given the carbon intensity of the sector, and the vital role that HSBC can play in helping to accelerate a shift away from coal-dependent activities, particularly in Asia,” the letter reads.

The letter ends with a warning that the coalition will keep a close watch on the bank’s activities. “While we have withdrawn the shareholder resolution this year, we may take further action next year if we are unsatisfied with the bank’s progress,” the coalition said.

In 2019, Share Action facilitated a similar resolution for Barclays AGM, which saw the bank respond with its plan, similar to the developments at HSBC.

Local banks and lucrative fossil-fuel assets

Five South African banks have put forward climate risk-related shareholder resolutions over the past few years. In 2019 Standard Bank and FirstRand tabled resolutions on climate-risk disclosure, and in 2020 Nedbank and Absa followed suit.

Just Share, a nonprofit shareholder activism and engagement organisation in South Africa, believes it is almost business as usual for banks operating on the continent.

“One of the three objectives of the Paris Agreement is to make finance flows compatible with the transition to a low-carbon economy. So, if you’re a bank that claims to support the Paris goals, you’d be setting ambitious targets for rapidly and responsibly phasing out funding to existing fossil fuel projects and excluding finance for new ones,” Just Share director Tracey Davies wrote in an opinion piece.

“But in the banking world, it seems you can simultaneously support the Paris goals and plan to expand fossil fuel funding hugely.”

In 2020 Investec became the first South African bank to release a separate report aligned with the recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

The Financial Sustainability Board created the TCFD to improve and increase reporting of climate-related financial information. Investec’s report discloses all fossil-fuel risk exposures in its portfolio to shareholders.

In the same year, the bank released a group fossil fuel policy, committing to releasing its exposures.

“Investec’s climate change report does not fully align with the TCFD recommendations, and there are some significant gaps: for example, the bank has not conducted any climate scenario analysis (although it plans to do so in the financial year to March 2021). It also does not set out any targets for carbon-emission metrics, which is essential for achieving alignment with climate goals.

“However, the report clearly articulates a plan for ongoing improvement in disclosures, and the publication of this first report will also allow stakeholders to track the bank’s progress in meeting its commitments,” Just Share said in a statement.

According to the TCFD, chaired by Michael Bloomberg, the financial crisis of 2007-2008 was an important reminder of the repercussions that weak corporate-governance and risk-management practices can have on asset values.

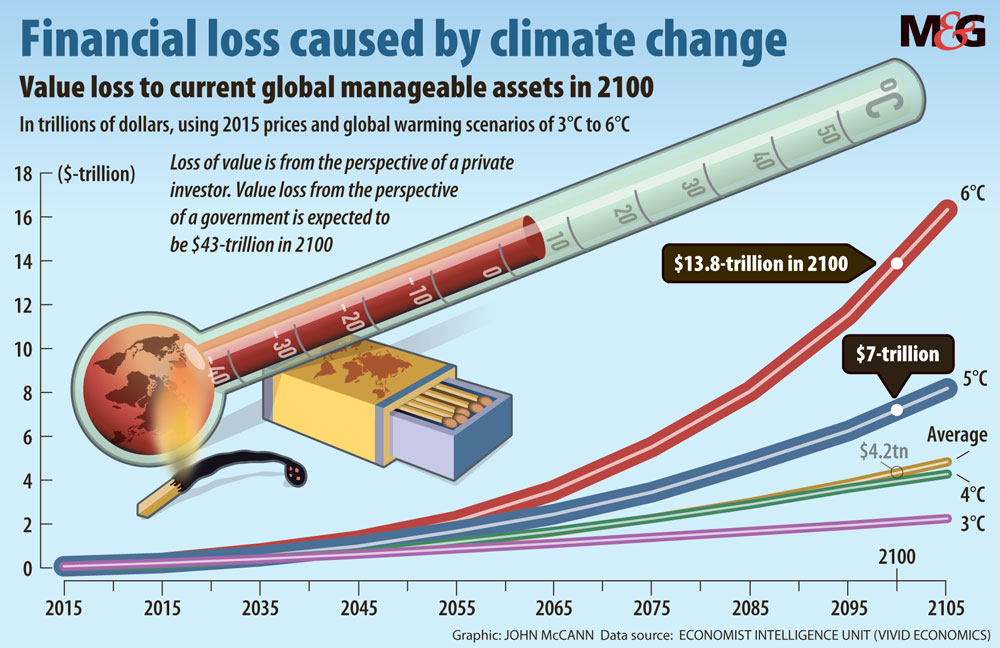

One study by the Economist Intelligence Unit, The Cost of Inaction: Recognising the Value at Risk from Climate Change, found that the estimated value at risk to the total global stock of manageable assets as a result of climate change ranged from $4.2-trillion to $43-trillion between now and the end of the century.

This value at risk depends on different scenarios of warming. For example, the researchers estimated, using this model, that warming of 5°C could result in $7-trillion in losses — more than the total market capitalisation of the London Stock Exchange; a rise to 6°C of warming could lead to a present-value loss of $13.8-trillion of manageable financial assets, about 10% of the global total.

When the expected losses for governments and socioeconomic effects are added to this, the expected value of a future with 6°C of warming represents present value losses worth $43-trillion.

According to the TCFD report, “Organisations that invest in activities that may not be viable in the longer term may be less resilient to the transition to a lower-carbon economy, and their investors will likely experience lower returns.

“Compounding the effect on longer-term returns is the risk that present valuations do not adequately factor in climate-related risks because of insufficient information,” the report continues. “As such, long-term investors need adequate information on how organisations are preparing for a lower-carbon economy.”

Climate action in the financial sector is gaining momentum. Still, experts warn that the voluntary and non-legally binding policies adopted by many of its major role players leave room for new fossil-fuel projects to continue unabated in the absence of legal, regulatory frameworks that fall strictly in line with the recommendations by the world’s top climate scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Climate change and sovereign credit ratings

A team of economists at the Cambridge Judge Business School have warned that the first “climate smart” sovereign credit ratings suggest global warming ratings downgrades as early as 2030.

The economists used artificial intelligence to simulate the effects of climate change on S&P Global Ratings credit ratings for 108 countries.

They assessed this over the next 10, 30 and 50 years, and by the end of the century.

“The majority of countries in our sample will suffer downgrades by 2030 if the current trajectory of carbon emissions is maintained. Virtually all countries, whether rich or poor, hot or cold, will be downgraded by 2100,” said co-author Dr Kamiar Mohaddes.

“Keeping to the Paris Agreement will be tough, but our estimates strongly suggest that stringent climate policy will significantly reduce the impact on ratings.”

New coal power plants not in tune with Paris Agreement

According to scientists, at present, the world is not tracking towards a Paris Agreement-compatible phase-out of coal. A paper published in Climate Analytics shows that current and planned coal-fired power plants globally will lead to a generation increase of 3% by 2030 compared to 2010 levels.

“If the world follows these present trends, this will lead to cumulative emissions from coal-power generation more than three times larger than what would be compatible with the Paris Agreement by 2050,” said the paper, titled Global and regional coal phase-out requirements of the Paris Agreement: Insights from the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] Special Report on 1.5°C.

The 2018 IPCC report warns of catastrophic consequences to the world’s most vulnerable social and economic status as a result of extreme weather and ocean heating.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa