(Stefan Wermuth/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

A Yemeni spy chief implicated in torture. The sons of an Azerbaijani strongman who rules a mountainous territory as his own private fiefdom. Bureaucrats accused of looting Venezuela’s oil wealth and hastening its descent into a humanitarian crisis.

They come from all over the world, each associated with a different corrupt, authoritarian regime and each enriching themselves in their own way. But there is one thing that unites them: where they kept their money.

After its luxury watches, snow-capped mountains and superior chocolates, the Alpine nation of Switzerland is perhaps known best for its secretive banking sector. And at the heart of that sector is Credit Suisse, which over its 166-year history has become one of the world’s most important financial institutions.

With nearly 50 000 employees and Sf1.5-trillion in assets under management for 1.5-million clients, this banking behemoth is still just the second-largest bank in Switzerland, a testament to how central the banking sector is to this wealthy and comfortable nation.

But, as a new global investigation spearheaded by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) reveals, this glittering success has its murky side.

Journalists have obtained leaked records identifying more than 18 000 accounts belonging to foreign customers who stashed their money at Credit Suisse. The records are nowhere near a complete list of the bank’s clients, but they provide a revealing glimpse behind the curtain of Swiss banking secrecy.

More than 160 reporters from 48 outlets spent months poring through the data — and found that dozens of the accounts belonged to corrupt politicians, criminals, spies, dictators and other dubious characters. These are not obscure names, their misdeeds often identifiable through a simple Google search. And yet, their accounts — which collectively held more than $8-billion — remained open for years.

Exchange rates

The accounts in this story are denominated in Swiss francs. Since the value of the franc has fluctuated over time, we have converted the account holdings to their historic US dollar equivalents.

Credit Suisse’s clients included the family of an Egyptian intelligence chief who oversaw torture of terrorism suspects for the CIA; an Italian accused of laundering criminal funds for the infamous ‘Ndrangheta criminal group; a German executive who bribed Nigerian officials for telecoms contracts; and Jordan’s King Abdullah II, who held a single account worth Sf230-million ($223-million) at its peak, even as his country raked in billions in foreign aid.

Venezuelan elites accused of plundering the state oil firm funnelled hundreds of millions of dollars into Credit Suisse accounts. The money flowed during a period when widespread looting from government coffers precipitated an economic collapse that has prompted six million people to flee the country and driven others into near starvation. The bank kept its Venezuelan clients’ accounts open even as global media exposed corruption cases against many of them.

Compliance experts who reviewed OCCRP’s findings said many of these people should not have been allowed to bank at Credit Suisse at all.

“People should not have access to the system if what they are carrying is corrupt money,” said Graham Barrow, an independent expert on financial crime. “The bank has a clear duty to ensure that the funds it handles have clear and legitimate provenance.”

Credit Suisse is not the only culprit. Many major banks and financial-service firms have faced similar scandals over the years. Many have then pledged to reform. And yet — as projects like this one reveal — they have continued to allow dodgy clients who have enriched themselves in countries with poor legal systems and lax oversight to safeguard their wealth in some of the safest and most secure places in the world.

“The irony is that Switzerland has become the place for dirty money to go because it is pure, well-managed, reliable,” says James Henry, a senior adviser to the UK charity Tax Justice Network who has studied tax evasion at Credit Suisse. “The business model of taking money out of poor countries is the problem.”

Asked to comment on the findings of the Suisse Secrets project, Credit Suisse said that risk management was “at the very core of our business”. While refusing to discuss individual customers, the bank said that they were “predominantly historical” and that an “overwhelming majority” of problem accounts identified by journalists “are today closed or were in the process of closure prior to the receipt of the press inquiries”.

“As a leading global financial institution, Credit Suisse is deeply aware of its responsibility to clients, and the financial system as a whole to ensure that the highest standards of conduct are upheld,” it added.

Insider opinions

OCCRP talked to more than a dozen former and current Credit Suisse employees to see if they could explain why the bank took on so many problematic clients. None would talk on the record, saying the bank was highly litigious against former employees, and none offered documentary proof for their comments. However, many of those interviewed mentioned the same issues, and there was consensus about some problems.

While some said compliance was diligent and had improved considerably in recent years, most talked of a highly toxic corporate culture that incentivised taking on risk to maximise profits — and bonuses.

Employees said bonuses were tied to how much “net new money” they brought in.

“The bank incentivises a banker to look the other way with an account they know to be toxic,” said a former senior manager in private banking. “If you close a toxic account, especially a large account in excess of $20-million, the banker finds himself in a deep hole. A deep hole that is almost impossible to get out of.”

This has led to a culture, Credit Suisse employees say, where there are two sets of rules for two sets of clients: the rich and the ultra-rich.

“Due diligence of customers and accounts –– say at a level of $1-million –– are very thorough,” said a former senior executive. “But when it comes to high-net-worth accounts, bosses encourage everyone to look the other way and managers get intimidated about their bonuses and job security.”

In addition, very big accounts are kept so secret that only a few senior executives might know who owns them.

“When someone wants to engage in money-laundering after he loots assets of the country, for example, he needs to transfer the money. So holders of big accounts go directly to the very senior managers,” he said.

The system was based on plausible deniability, said former employees. Bankers are given strict rules, but the incentives are to ignore them.

“The bank’s compliance department are masters of plausible deniability,” the former senior manager said. “Never ask a question you do not want to know the answer to.”

“It’s never the bank’s fault, it’s always this bad apple employee who is responsible for something bad happening,” one manager said. The end result is a disconnect between the bank and its employees.

“The kind of people the bank attracts are mercenaries, and they all look to enrich themselves first — probably understanding that there is no real relationship with the bank. You’re only there for as long as you make money, however you make that money,” the manager said.

“You don’t need to worry about what happens eight to 10 years from now, because you’re unlikely to be there. Usually, that’s how long it takes for deals to blow up.”

These insider accounts echo allegations Credit Suisse is now fighting in court, in the first criminal case ever launched against a Swiss bank in Switzerland. Prosecutors say the bank allowed a group of Bulgarian cocaine smugglers to launder €146-million in drug money through Credit Suisse accounts.

Senior managers are accused of ignoring many warnings that their Bulgarian clients were up to no good, including the fact that they were depositing suitcases of cash — suitcases at least one other Swiss bank refused. Even after two of the criminals were assassinated and named in the media as cocaine traffickers, the bank looked the other way.

A banker who dealt with the Bulgarians testified that Credit Suisse trained her carefully on how to present herself to potential clients and on the importance of Swiss banking secrecy, but not on compliance, the Financial Times reported this month.

As evidence, one of her compliance tests was presented in court. She had answered only a quarter of the questions correctly.

The bank was also criticised in a leaked 2017 report by Finma, the Swiss financial regulator, which revealed a culture in which senior managers were prepared to “whitewash” and “turn a blind eye” to compliance failures when a star banker defrauded lucrative clients.

“There were even attempts to gloss over the violations,” the report said.

Pitching privacy

Swiss banks sell privacy. Reporters from OCCRP wanted to find out how.

A journalist got in touch with Credit Suisse and asked if she could open an account on behalf of an investor from an African country. The bank’s representatives were careful about what they said and preferred to talk by phone rather than email. From the beginning their focus made it clear that privacy was what they were selling.

“There are limited people even within the bank who would be able to access your account information,” a Credit Suisse vice-president assured the reporter.

“Information is treated strictly with secrecy and on a need-to-know basis,” said another banker in an email.

Although Credit Suisse still offers what it calls “numbered relationships” at a cost of about $3 000 per year, the bank steered the African investor towards other options.

“Numbered accounts are a service we are actually phasing out, as the protections offered by this have diminished greatly over the years,” said the Zurich-based vice-president overseeing emerging markets.

The secrecy of numbered accounts took a series of hits in the 2010s, when repeated tax-evasion scandals led to international pressure on Switzerland to share clients’ tax information with foreign governments –– although the agreement excluded developing countries, which Credit Suisse said were its biggest target markets.

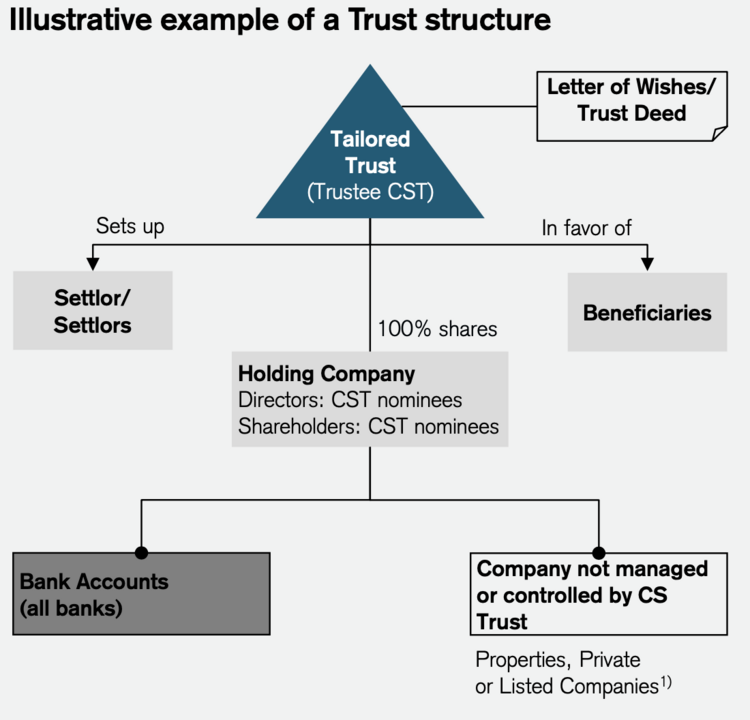

Top Credit Suisse executives proposed several alternatives to numbered accounts in its presentation to the prospective client, including putting her money in a trust.

Trusts are a common financial vehicle in many jurisdictions, but they have come under fire from transparency advocates because they allow the true owners to hide behind “nominees”, who can act as shareholders and directors.

In the presentation, Credit Suisse indicated that its staff can act as nominee shareholders and directors in holding companies, trusts and bank accounts, which can be registered to anonymous holding companies. That service would create legal layers of ownership that would allow wealthy individuals to distance themselves from their wealth.

Trusts have not been widely used in Switzerland until recently — in large part because banking secrecy filled the same role. But that may be about to change. Last month, Switzerland introduced a new draft law that would allow Swiss bankers to create trusts in Switzerland for the first time.

Sebastian Guex, a professor of history at the University of Lausanne who studies the Swiss banking industry, said this was a direct reaction to new tax-sharing agreements that opened up wealth stored in Swiss banks to more scrutiny.

“Swiss bankers have found solutions that will allow them to continue to hide the wealth of the most interesting clients, those who bring in the most profits, [that is] the famous ultra-high-net-worth individuals,” he told The Guardian.

“These solutions will involve the creation of tax-evasion systems for this clientele based on the family foundation or, even more so, on the Anglo-Saxon legal institution, the trust.”

A secret history

Switzerland’s reputation for financial secrecy goes back hundreds of years.

In 1713, the Council of Geneva banned bankers from divulging their clients’ details to safeguard the interests of the French monarchy, which wanted to obscure its dealings with banks in a “heretical” protestant country.

Switzerland’s internationally recognised status of neutrality, dating from the 19th century, helped to attract huge amounts of capital from abroad, as did an expanding tourism sector that was trying to lure Europe’s wealthiest for long stays in lakeside palaces or Alpine sanatoriums.

“To add something that other countries didn’t have, they also adopted tax measures to stimulate rich people coming from outside to stay long in Switzerland,” said Guex.

Switzerland became a tax haven, and started competing with France and other European banking heavyweights to attract foreign capital. Whether it was the mountains or the laws, it worked — wealthy foreigners started arriving in droves, and brought their money with them.

With the outbreak of World War I, wealthy Europeans turned to Switzerland to insulate themselves from economic instability and tax hikes associated with the war effort. World War II repeated the pattern, and while most of Europe was left in ruins, neutral Switzerland came out unscathed and flush with deposits from all sides.

In 1934 Switzerland upped its secrecy with the Banking Act, a law which promised to jail any bank employee seeking to disclose confidential customer information.

More recently, Switzerland has made changes to the way its banking sector is regulated.

After the 2008 financial crash, the country agreed to lift the veil on thousands of accounts after a UBS employee told US prosecutors how the bank was helping Americans hide their assets.

But the agreement also secured the dismissal of US charges of enabling tax evasion and raised the maximum sentence for breaching financial secrecy laws from six months to three years.

Experts say the law essentially criminalises whistleblowing, silencing insiders and even journalists who may want to expose wrongdoing within a Swiss bank.

Article 47 of Switzerland’s banking law puts journalists in the country at risk of being prosecuted for merely possessing, much less publishing, private banking data. For that reason, Tamedia, a Swiss media group that was approached as a partner in the Suisse Secrets investigation, chose not to participate.

“This law is a massive restriction of press freedom in Switzerland,” said Arthur Rutishauser, Tamedia’s chief editor. “It only serves to censor and intimidate the media. The law can protect criminals and their assets. Journalists who try to expose them risk criminal proceedings.”

“It seems like a law from the 1800s,” said Jeffrey Neiman, a US lawyer representing Credit Suisse whistleblowers. “That law demonises those who come forward with good information to expose corruption.”

Basel, Switzerland, in the 19th century

Basel, Switzerland, in the 19th century

Buying secrecy

If Credit Suisse was selling secrecy, there were plenty of buyers.

The leaked records analysed by reporters show accounts held by several alleged human rights abusers, such as Algeria’s former defence minister Khaled Nezzar. As head of the armed forces, Nezzar was considered Algeria’s de facto leader from 1991 to 1993, when the country was embroiled in a civil war marked by atrocities committed against civilians.

Despite well-publicised allegations against him, Nezzar was a Credit Suisse client, holding two accounts worth at least Sf2-million ($1.6 million at the time). It remained open until 2013, two years after an investigation into his involvement in war crimes was opened in Switzerland.

His lawyers said he “strongly denies any wrongdoing. He did not commit nor did he order war crimes. He did not provide assistance to, nor did he knowingly allow the commission of war crimes.”

The two sons of an Azerbaijani strongman who rules an isolated region of the country with an iron fist also had Credit Suisse accounts. As their father’s regime imposed his brutal whims on the population of Nakhchivan — at one point even banning them from baking bread at home or hanging laundry on balconies — Rza and Seymur Talibov used their Swiss bank accounts to take in millions of dollars from shell companies associated with money-laundering systems.

Khaled Nezzar in 2012. (OCRP)

Khaled Nezzar in 2012. (OCRP)Credit Suisse also offered banking services to key figures implicated in corruption scandals in some of the poorest countries in the world. In Angola, a disgraced banker under investigation in Portugal after the bank he led collapsed with $5.7-billion in untraceable debt, held several Credit Suisse accounts, some of which are being looked at by Portuguese prosecutors.

In Kenya, Credit Suisse banked a key player in a huge corruption scandal even after authorities declared him wanted in a criminal probe. Millions of dollars appeared to be withdrawn from the account even as investigators in Switzerland and Kenya were trying to trace the stolen funds.

A number of Central Asian names also appear in the leaked data. Though they make up only a small fraction of the clients identified by reporters, billions of Swiss francs passed through their accounts. These people represent large swaths of the Central Asian elite, including oligarchs who made their wealth from natural resource extraction, ministers, and other top officials, some of whom have been convicted of massive corruption. Even the children of two former presidents, Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev and Uzbekistan’s Islam Karimov, controlled Credit Suisse accounts — while the two men were still in power.

Another Credit Suisse client was former Venezuelan spy chief Carlos Luis Aguilera Borjas. Aguilera was close to former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who died in 2013 after establishing a socialist regime that has become mired in corruption, with officials looting state funds and stashing the money overseas.

In 2001, Aguilera was installed as head of the secret service, where he kept a low profile, avoiding interviews and photographs.

Carlos Luis Aguilera Borjas (OCRP)

Carlos Luis Aguilera Borjas (OCRP)“They call him ‘The Invisible One’, Carlos Aguilera, the head of the political police. Nobody sees him. I know where he is,” Chávez said in a 2002 national broadcast of his weekly TV show, Hello President. But Aguilera fell out of favour later that year after failing to prevent a coup attempt that almost toppled Chávez. He left his secret service post and entered the private sector full time, amassing wealth most Venezuelans could only imagine.

In 2007, Aguilera became the major shareholder of Inversiones Dirca, a Venezuelan firm that secured a $1.85-billion contract the next year to renovate a Caracas metro line. There was no public bidding process, and Aguilera took a 4.8% commission worth almost $90-million.

In 2011, two accounts were opened in Aguilera’s name and credited with at least Sf7.8-million ($8.6 million). The Aguilera accounts were still open well into the last decade when the Suisse Secrets data was collected.

“By any definition, he’s high risk,” said Barrow, the financial crime expert, adding that banks are responsible for making sure the sources of funds from politically connected customers are legitimate.

Aguilera did not respond to OCCRP’s emailed questions.

‘How many rogue bankers do you need’

Credit Suisse has repeatedly pledged to crack down on illicit funds, after a string of scandals beginning more than two decades ago with the death of an infamous Nigerian dictator. After Sani Abacha died in 1998, it emerged that Credit Suisse had helped to stash some of the billions of dollars his family had looted from his country.

In an effort to defuse the fallout from that revelation, the bank’s then-chairman said in 2000 that it had “continuously improved … control procedures and compliance with them.”

Later that year, Credit Suisse became a founding member of the Wolfsberg Group, an international banking association assembled to curb illicit financial flows.

“The bank will endeavour to accept only those clients whose source of wealth and funds can be reasonably established to be legitimate,” read a Wolfsberg Group mission statement in 2000.

Yet Credit Suisse’s promises to clean up did little to prevent its entanglement in criminal cases for many years to come.

From money-laundering to tax evasion, Credit Suisse has repeatedly broken rules or fallen short on regulations during the past two decades.

“The bank likes to say it’s just rogue bankers,” said Jeffrey Neiman, the American lawyer. “But how many rogue bankers do you need to have before you start having a rogue bank?”

Neiman does not represent the source of the Suisse Secrets leak, but his clients include a whistleblower who told a US court last year that Credit Suisse continued to help American citizens illegally hide hundreds of millions of dollars offshore. If true, this would be a violation of a 2014 pledge the bank made to settle criminal charges in the US.

The US department of justice and the powerful senate finance committee are currently investigating whether Credit Suisse continued to facilitate tax evasion after it settled and paid a record $1.3-billion fine in 2014.

The bank’s chairman at the time, Urs Rohner, conceded mistakes in its handling of the tax-evasion scandal but told a Swiss television station that he himself had “clean hands”.

Recalling this incident in a recent interview with OCCRP, Swiss MP Gerhard Andrey said he was still incredulous that Credit Suisse executives never accepted personal responsibility for the scandal.

“He’s the head of the company,” Andrey said by phone as he paced the foyer of the Swiss parliament, where he represents the Green Party. “If you’re CEO or president, you can’t say, ‘It has nothing to do with me’, because you’re responsible for defining the culture. Culture is defined top-down by senior staff, the board and executives.”

Experts say that fines aren’t enough: large and wealthy banks won’t change until they face more serious measures, like the suspension of licences or prosecution of individual leaders.

Frank Vogl, a former World Bank official who is now an anti-kleptocracy campaigner, said bankers appear to treat even very large fines as “merely the costs of doing business”.

He said US and European authorities had filed an “astounding” number of cases against Swiss and Switzerland-based banks — “yet not a single chairman of such banks has ever been personally prosecuted, or even lost his job because of those crimes”.

“CEOs have to go to jail for this to hit home,” said Henry of Tax Justice Network, noting that the $1.3-billion penalty paid by Credit Suisse was even tax deductible.

Critics accuse Credit Suisse of negligence, but they reserve much of the blame for Switzerland’s government, which is responsible for a lax regulatory environment and laws that punish those who speak out against corruption.

Stefan Lenz, a Swiss former federal prosecutor who led major corruption cases, said there are very few investigations targeting Swiss banks or their management for accepting illicit money. “There seems to be a lack of both political will and law enforcement resources,” Lenz told OCCRP.

Andrey, the Green Party MP, urged the government to take action for the sake of its citizens.

“I’m a proud Swiss,” he said. “It hurts me when banks spoil my country’s reputation with this behaviour.”

“People are angry at the scandals that have already been exposed — and we don’t even know the unknown scandals.”

Research on this story was provided by OCCRP ID. Data expertise was provided by OCCRP’s Data Team. Fact-checking was provided by the OCCRP Fact-Checking Desk. This story was first published by the OCCRP.